I had a long break over Christmas and these are a few of the meals I had during that break: at the local pizza joint a pepperoni pizza washed down with beer, a trip to the German club where I had a pork knuckle with sauerkraut washed down with beer, a trip to a French bistro where I had the cheese platter washed down with wine, breakfast at a cafe with kimchi scrambled eggs washed down with hot chocolate, dinner at a Thai restaurant including Esan sausages, fried rice and fish curry washed down with beer (and wine) and, because I had a hangover, a breakfast at home of yoghurt and honey washed down with water.

What do you notice about this pretty nondescript list? Yeah, the obvious thing is that I drink too much, but it was over the Christmas break so, you know. The thing I am really trying to highlight is that every one of those meals was predominantly made up of fermented foods. Beer, wine, bread, sausages, fish sauce, chocolate and yoghurt are all fermented foods and this is just a tiny sample, there are many, many more fermented foods. I never got into kombucha, but fermented, likewise vinegar, miso, soy sauce, Worcestershire sauce, pickles, chutneys, creme fraiche, sour cream and olives. And these are just fermented foods a boring middle class Australian like myself would come across, if you start looking into other cultures you’ll find hundreds of other foods that are the result of fermentation. We clearly owe a lot to the microbes that ferment our food because once you start looking fermentation is everywhere.

This shouldn’t be surprising, fermentation is, and has been throughout our history, integral to our relationship with food but, somehow, we don’t really notice it any more. A lot of this has to do with the way the modern world has changed how we source and prepare our food. We no longer grow our own food, we don’t need to preserve anything when we have refrigerators and getting fresh food is just a trip to the supermarket. But when we lived from harvest to harvest fermentation was one of the ways we could preserve our food because the byproducts of fermentation, acids and alcohols, inhibit the growth of bacteria that cause spoilage. Raw vegetables rot but vegetables fermented in salty water can last for months, even years, and so fermentation was just something you did so you didn’t starve during the cold winter months or, if you were in the tropics, to prevent your food quickly spoiling in the harsh heat and humidity.

But it was never all about preservation. Fermentation can also improve the experience of eating food or even make some inedible foods edible, bread without the lightness and flavour that fermentation brings is, well, flat and unfermented cocoa beans taste nothing like chocolate. We may have originally used fermentation for preservation but it is clear that we quickly developed a taste for the flavours and other byproducts that fermentation brings to the table. Take one of my favourite fermented foods, beer. Originally beer may have been a way to convert barley into something a little longer lasting but I doubt it took too long before our ancestors realised the benefits of that interesting byproduct of fermentation, ethanol. Fermentation turned a pretty bland and uninteresting grain into a tasty beverage that, for most of history, was safer than the drinking water and could, under the right circumstances, turn you into the life of the party. Our ancestors were so impressed with beer that ever since it was first made, some 15,000 years ago, it has never really lost it’s popularity. That’s some happy hour.

To understand how fermentation preserves and improves our food we need to take a side trip into biochemistry. Key to understanding fermentation is a cellular process called respiration that plays an important role in the cycle of energy production and consumption in a living cell. Simply put respiration is the chemical reaction that takes a molecule called adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and an organic molecule, glucose for example, and produces a molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is very important molecule for life, it is found in all living organisms and it is often likened to an ‘energy currency’, kind of a token that a cell can cash in to get the energy to drive a biochemical reaction. In the cell respiration takes place in a subcellular component called the mitochondria and because of this mitochondria are often called the power houses of the cell. A cell is in a constant cycle of importing ADP to the mitochondria, producing ATP and then exporting this ATP to the rest of the cell where it is broken down into ADP to provide energy for all the other biochemical reactions in the cell.

The reason we breath and transport oxygen to every cell in our body is that respiration works best in the presence of oxygen. When oxygen is present a cell will use a highly efficient set of chemical reactions that we collectively refer to as aerobic respiration. Fermentation, on the other hand, is a different set of reactions that is used by cells in the absence of oxygen, it is a type of anaerobic respiration. Fermentation is much less efficient than aerobic respiration, no organism lives on fermentation alone, but it does provides a fallback mechanism for cells to produce energy when there is little or no oxygen. Although we normally associate fermentation with single celled organisms, like yeast and bacteria, it is also found in more complex organisms. Human muscle cells, for example, can use fermentation chemistry when the blood stream cannot deliver enough oxygen for normal respiration, an ability that comes in useful when we are participating in strenuous activity.

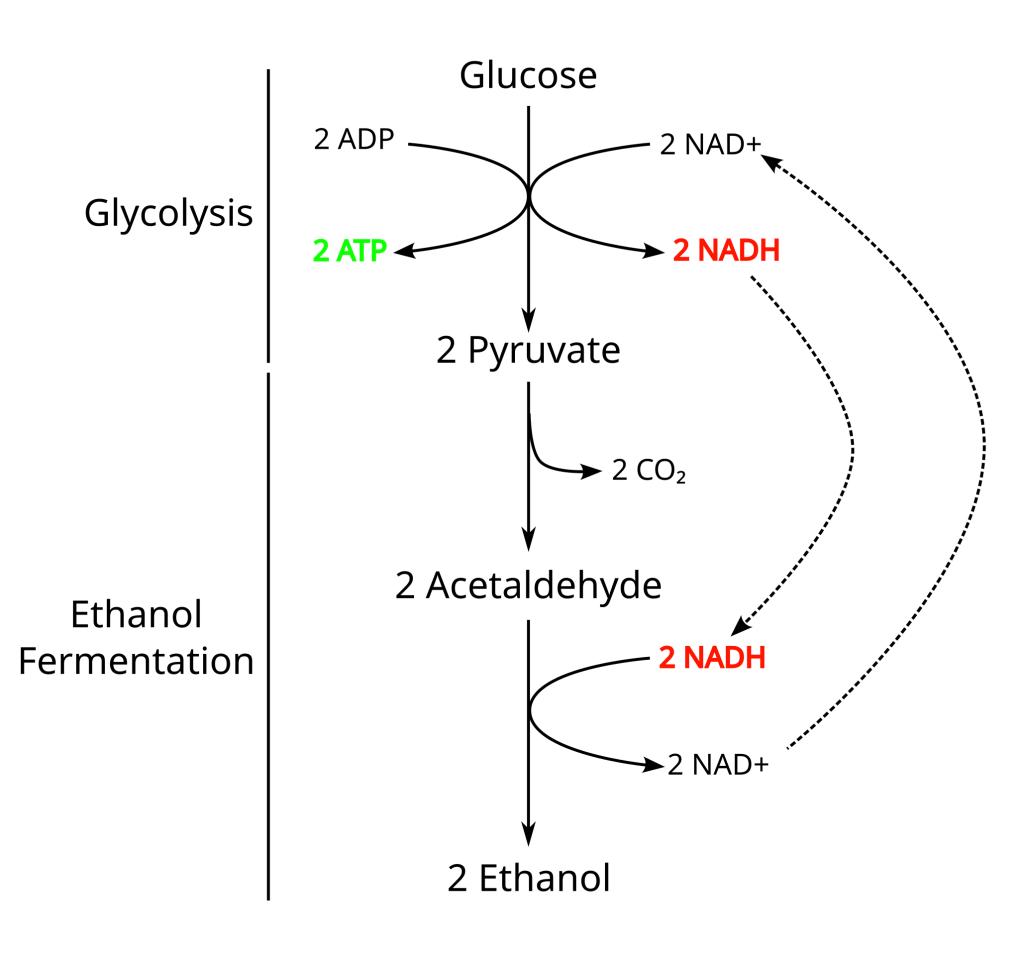

The interesting thing about fermentation is that different cells can use different types of fermentation reactions. While all fermentation reactions produce ATP, different organisms can use different starting materials and use a chemistry that results in different byproducts. The figure below will give biochemists painful flashbacks to undergraduate classes but it also shows the types of byproducts that can be produced during fermentation of glucose. Types of fermentation are often referred to by their major byproducts and the two types that are important to foodies are lactic acid and ethanol fermentation. Bacterial lactic acid fermentation is used to produce things like yoghurt and sour cream, the bacteria using the lactose in milk as it’s starting material. It is also lactic acid fermentation that gives you sore muscles after strenuous exercise, the anaerobic fermentation in human muscle cells produces lactic acid from molecules of glucose.

Ethanol fermentation, on the other hand, is a fermentation where glucose is converted to two pyruvate (in a reaction known as glycolysis) and then to two each of ethanol, carbon dioxide and ATP molecules. This type of fermentation is normally found in yeast, though some bacteria and molds also use this chemistry. Beer and wine are famously produced with yeast using ethanol fermentation but another major food that utilises byproducts of ethanol fermentation is bread. Yep, there is alcohol in bread, well before it is cooked anyway, the high heat of the oven burns off the alcohol, but the carbon dioxide that is produced during fermentation is what makes the dough rise and gives us our fluffy bread.

OK that’s a lot of chemistry so maybe it’s time to start looking at beer like I promised. With this chemistry under our belt I’m betting you could pretty much throw some barley in a bucket with some water and you’ll end up with a beer of sorts, at the least some type of fermented barley juice. Much like sourdough, natural yeasts in the environment would start fermenting free sugars found in the germinating barley and hey presto beer. I’m not sure how it would taste and I’m not inclined to find out but I imagine one of our ancestors did find out and saw enough potential in his or her barley juice to keep at it. Certainly, by 6000 BC humans in Mesopotamia were drinking beer and the Egyptians loved it (see here for a recreation of Egyptian beer) and elevated beer making into an art form. An art form that was expanded on in Europe where most of the beer we drink today originates.

I say art form because when it comes down to it anyone could make a fermented barley juice but thousands of years of human beer production has resulted in a diverse array of different beers that use the science of fermentation to produce a whole range of flavours and textures in these beers. Like other fermented products, wine and cheese for example, making a tasty beer is not so much about the science but the choices made by the producer during the production process. The science of fermentation, the chemistry of sugars and even the mixture of yeast that is used in the fermentation is the scientific structure around which flavour is built using the judgement of the brewer and his or her success is judged by the opinions of those that consume it. So if you see some click bait like ‘Scientists create the perfect beer’ don’t click, there is no perfect beer just the style of beer that you like to drink.

Having said that I do want to quickly step through the process of making beer and point out some of the places where the science is an important consideration for the brewer. So if we have a mixture of barley grain and water and we know that alcoholic fermentation in yeast works using glucose molecules then the first thing to do is work out where that sugar will come from. You could just add sugar but with barley we already have a stack of starch that is made up of glucose molecules (see the sugar and fries posts for more on starch). So for our beer we want to start breaking down the starch into sugars that the yeast can then use for fermentation.

To achieve this you need enzymes that will catalyse the breakdown of starch into glucose, a process called saccharification (if you are unsure what enzymes are check out the fries post but quickly enzymes are a protein that will cause a chemical reaction to proceed, in this case the breakdown of starch into glucose). Historically, we’ve found these enzymes in a few different places. In the east Aspergillus oryzae, a mold that grows on cooked rice, secretes enzymes capable of breaking down starch and it is used to saccharify starchs for a wide range of fermentation processes, including sake, soy sauce and miso. A novel approach was developed in the new world where woman would, and sometimes still do, get the starch-digesting enzymes from their saliva by chewing on ground corn and spitting it into boiled corn to make a corn-based slightly alcoholic beverage called Chicha.

As much as I like the image of modern brewery workers sitting around and spitting chewed up barley into a bucket most modern beer making takes advantage of an enzymes found in barley itself. In a process called malting barley grains are allowed to germinate by soaking in cold water, at around 18C/64F. As the new plant sprouts it starts producing enzymes such as alpha- and beta-amylase and beta-glucanase that are able to breakdown plant cell walls and start converting some of the starch to glucose.

The precise amount of time, and starch breakdown achieved, is part of the art of beer making. The more starch breakdown you allow the more alcoholic your final product will be because of the amount of fermentable glucose liberated. It also affects the darkness of the beer as plenty of sugars means ample opportunity for Maillard reactions in subsequent steps (the same colour you see on your steak). Another strategy, used to maximise starch breakdown, is to hold the malt between 60-80C/140F-175F to maximise enzyme activity. This is the temperature range in which the starch-digesting enzymes operate most efficiently and we’ve seen a similar strategy before when looking at the activity of pectin methylesterase when making french fries.

Once the brewer is happy with the malt the mixture is put in a kiln and heated. Once again there are a lot of options at this stage, the malt can be heated slowly to a low final temperature (say around 80C) to preserve enzyme activity and keep colouring to a minimum. Alternatively it can be heated to 180C to kill all the enzymes and get a lot of colour from Maillard reactions. Or any combination of heat and time can be used to get the type of malt you want. Once again the art of beer making involves making a malt with the characteristics you want for your specific beer. Once kilned the malt can be kept for several months and for a specific beer multiple malts can be combined for the subsequent steps.

All we need to do now is brew our beer. To do this the malt is dissolved in hot water to form a mixture called the ‘wort’ (which I think is a wonderful medieval word that has survived to the modern age and to me brings to mind monasteries and weird haircuts). This step, called mashing, can be performed at different temperatures for different amounts of times at the discretion of the brewer. If they weren’t killed during kilning starch digesting enzymes will reactivate during mashing and so this is an opportunity to further manipulate the relative levels of fermentable sugars and longer chain sugars that can add body to the final product.

After mashing is completed hops are added to the wort and it is boiled. This inactivates any remaining enzymatic activity, pulls the flavour out of the hops, kills any microbes present and concentrates and deepens the colour of the wort. There is probably a whole new post in the chemistry of hops which are the flowers from Humulus lupulus but for now I’ll just say that the boiling helps solubilise phenolic acids found in the hops which gives beer it’s characteristic bitterness.

After boiling, the wort is cooled and yeast, or a mixture of different yeasts, is added and it begins fermenting, breaking down the free glucose and producing ethanol and other flavours via metabolic byproducts. Finally the beer is conditioned, which can involve many different processes designed to remove unwanted flavours, introduce carbonation, additional hops may be added for aromatic qualities and fining agents added to help remove particulates. The beer is then centrifuged to remove particulate matter and packaged.

A professional brewer or even someone who brews beer at home is probably yelling at me right now as I have skimmed many, many details. But this isn’t a guide to brewing beer just a vehicle to introduce some of the chemistry of fermentation and give a brief primer on the brewing process. If you want to start brewing your own beer, which I may be forced to do here in Australia if the government doesn’t stop raising beer taxes, there are plenty of home brewing resources you can get your hands on. In future posts I’ll have a look at other fermented posts which will be a lot easier now that we’ve got a good grip of the biochemistry behind fermentation.

Leave a comment