There is an old Indian parable of a king who wanted to reward a wise man who had invented chess. The wise old man asked for rice but had an unusual stipulation when was asked how much rice he wanted. He requested a single grain of rice to be put on the first square of a chessboard, two on the second, four on third and so on, doubling the amount of rice until all 64 squares were filled with rice. The king, thinking he was getting a great deal, readily agreed and so they began counting out the rice grains.

Those of us with a mortgage and an understanding of compound interest can see the trap immediately. The king was not so quick but by square 16 the total amount of rice on the board was over 65,000 grains of rice and he began to suspect something was up. Pausing, and doing some quick calculations he quickly realised that by square 32 there would be over 4 billion grains of rice owed and by square 64 a whopping 18 quintillion grains of rice. More rice than existed in all the world and well beyond any capacity of the King to pay. What happened next? Was the wise man not so wise to confuse a king this way? Well different versions of the story have the wise man either being executed or made a trusted adviser of the king so I guess we’ll never know for sure.

What we do have though is a good parable of exponential growth that we usually use to illustrate the power of compound interest. But, for a food scientist, it is rather more reminiscent of bacterial growth. Like the growing piles of rice bacterial growth is an exponential phenomenon that occurs through repeated doubling of a population. This exponential nature of bacterial growth is, and always has been, especially important in our food systems. Bacteria are as fond of our food as we are and, particularly for meat and other animal products, controlling bacterial growth is one of the major forces driving the way we preserve, store, cook and consume our food.

Because of exponential bacterial growth, as soon as animal products are produced the clock is ticking on the viability of that food for human consumption. Unless animal products are refrigerated, or otherwise preserved, bacteria will soon make them unfit for human consumption. Bacteria not only spoil animal products, causing undesirable changes in odour, taste and texture, but they can also cause direct harm, either by colonising our bodies and causing illness or by producing waste products that can make us very ill indeed. Even cooking is nothing but a temporary respite from bacterial attack, as soon as food starts cooling the bacteria will be rushing back in.

Given it’s importance the way that bacterial populations grow has been well described and almost all bacterial growth follows a well-defined pattern, passing through a series of well defined stages. Initially bacteria, once they have gotten themselves onto a suitable substrate, will enter the lag phase. During this time the colonising bacteria are not reproducing but they are metabolically active. Although the biochemistry of this phase is the least well understood, it is generally thought that the bacteria are producing macro-molecules needed for growth, repairing any damage and adapting to the conditions in their new home (temperature, pH, oxygen availability etc). The length of the lag phase can vary depending on the conditions and how much preparation is needed by the cells but eventually they will move into the log (or exponential) phase and this is where all the action happens.

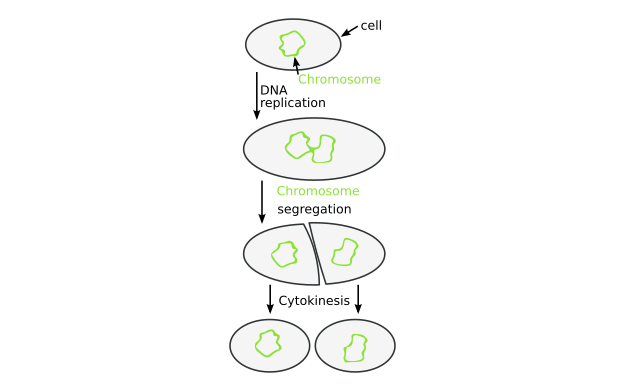

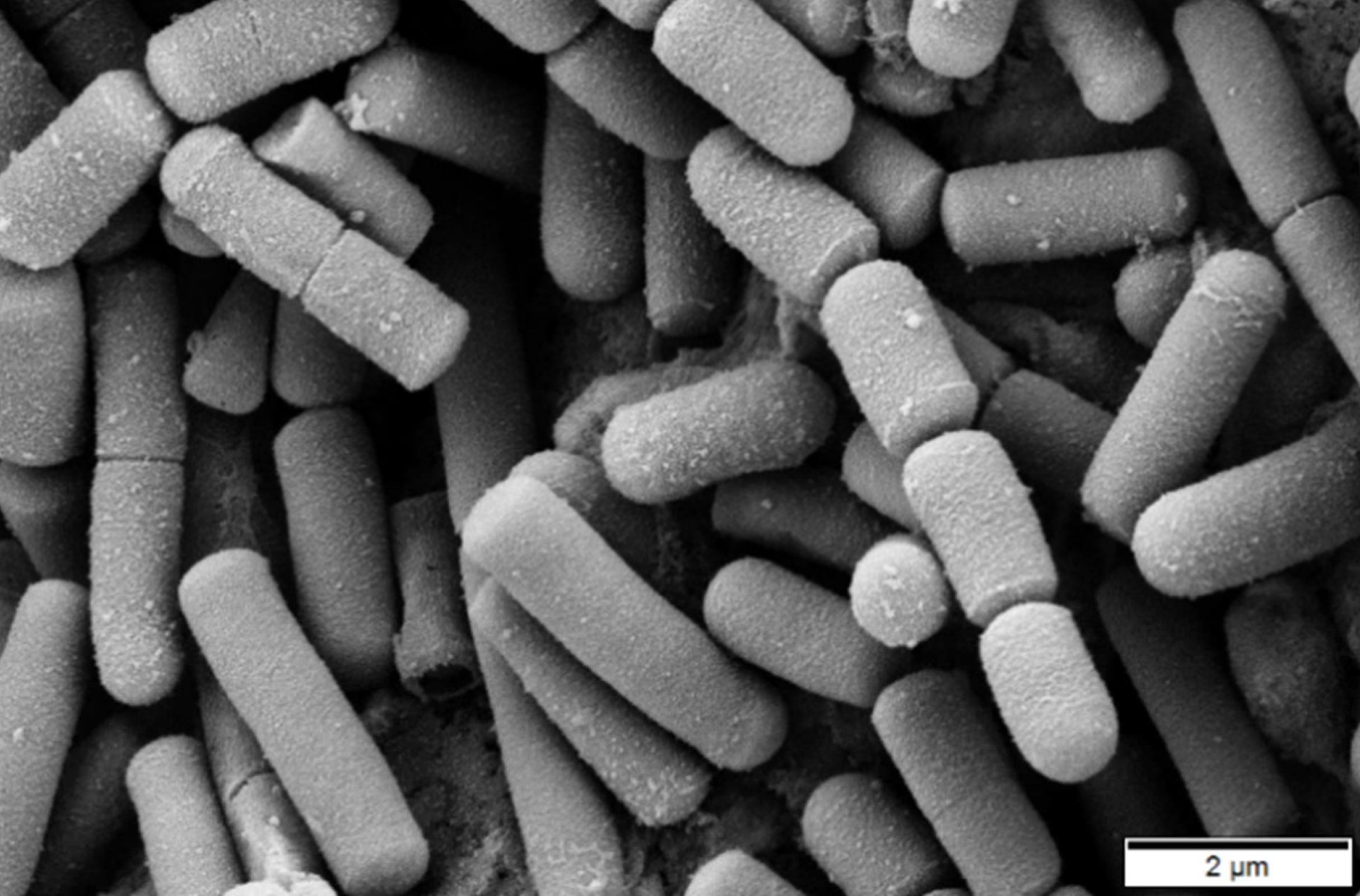

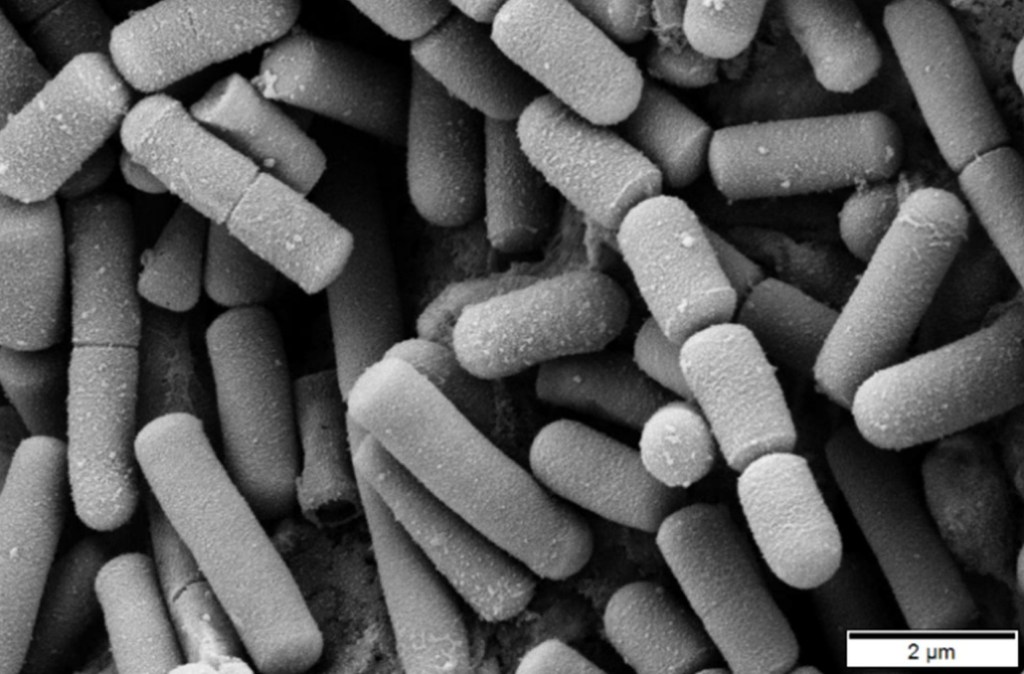

It is in the log phase that the bacterial colony can undergo explosive growth rapidly increasing its population. The secret to bacterial exponential growth is in the way that they reproduce. Although they capable of a limited type of sexual reproduction, in which they use a process called conjugation to exchange genetic material, the major mode of bacterial reproduction is an asexual process called binary fission. In binary fission a bacterial cell splits in two to form two daughter cells. To do so a bacteria will replicate it’s DNA, kept in a circular ‘chromosome’ called a nucleoid, and then split into two distinct daughter cells. This process can be completed pretty quickly. Some bacteria, like Escherichia coli for example, can complete a round of binary fission in about 10-20 minutes meaning a population can potentially double in size every ten minutes.

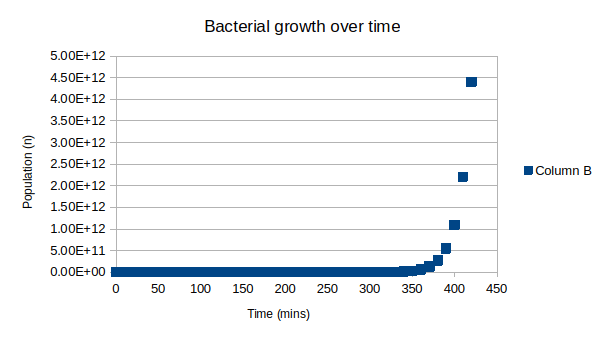

We know from the parable of the chessboard that consecutive doubling of a population can lead to an enormous final population after just a few iterations. To visualise this I’ve plotted a growth curve starting with a single bacterium that is undergoing binary fission every 10 minutes. To make things a bit easier to visualise I’ve followed the common convention of using the common logarithm (base 10) of the population count mainly because you get a straight line which is a lot easier to use than the exponential curve (you can see the raw exponential curve here if you want). Using this plot you can see, below, that after seven hours (420 minutes) our single bacterium will have around 4 trillion descendants. Note that this is the exact same geometrical progression as the parable of the chessboard and if you want to express things in chess squares rather than time we are on square 43.

Of course exponential growth cannot last for ever, eventually a point is reached where the available resources cannot support further population growth. Things like space, nutrients, water or oxygen can put a limit on further population growth and buildup of toxic by-products of bacterial metabolism can do the same thing. When this point is reached the population will enter a stationary phase where the ‘birth’ rate is greatly curtailed and the production of new bacteria becomes roughly equal to the death rate. The bacterial population will continue like this until resources are depleted and the population enters the death phase. The death phase is what it is says on the label, resources decline, waste products increase and the bacteria begin to die off.

So what does all this mean for our food? When an animal is slaughtered, for example, the exposed parts of the carcass will almost immediately be colonised by bacteria. Animals themselves are covered with bacteria and, though modern facilities should be pretty hygienic, it is a pretty safe assumption that there will be some bacterial contamination on the meat after an animal is slaughtered. The objective then becomes to stop any bacteria that are present from entering log phase growth. Traditionally meat needed to be either eaten immediately or preserved using smoke, fermentation, salt or drying, all ways of arresting bacterial growth. But in the modern world, although we still preserve meats for the flavour, to preserve fresh meat before consumption we use refrigeration.

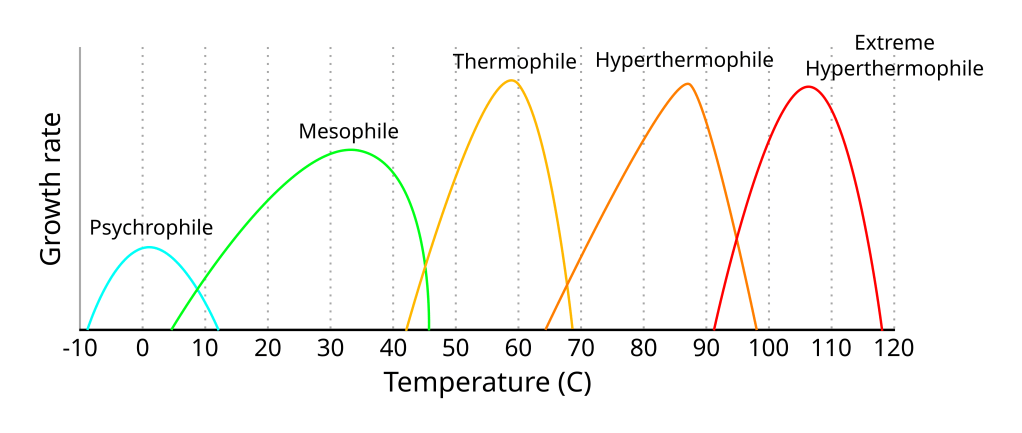

Refrigeration works because different species of bacteria have different temperature ranges that they are comfortable in. The ones we are mostly concerned with in food production are called mesophiles and these bacteria reproduce best between 20-45C, generally dying at temperatures above 65C. All the bacteria of our microbiome are mesophiles as are most of the bacteria responsible for food spoilage, food poisoning and disease. If food is kept at a temperature outside the mesophile range any bacteria present will not go into log phase growth (or they will do so very very slowly). The modern approach is to ensure our logistics networks never allow our animal products to stray into these optimal temperature ranges for mesophile bacteria.

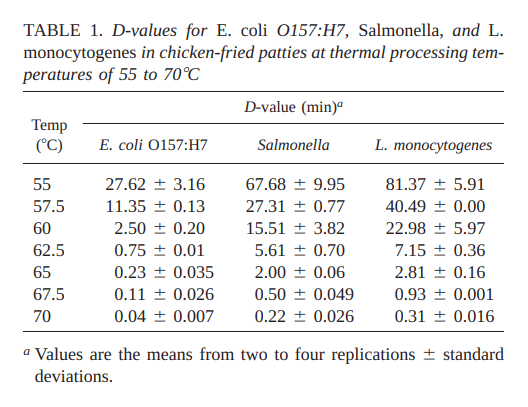

Bacterial temperature tolerance is also very important when we are cooking our food. Cooking has a few benefits: it can make food easier to eat, it can help with digestion and nutrient absorption and it also just makes food taste better. Importantly, however, cooking also helps by killing any bacterial contamination that may have occurred. To help quantify this scientists use the concept of decimal reduction time, usually denoted as ‘D’. The D value represents the amount of time is needed to reduce the amount of bacteria by 90% (i.e. a ten-fold or log10 reduction) at a specific temperature. For example, if we have 1000 cells of some hypothetical bacterial species and the D60 is 2 minutes then after 2 minutes at 60C only 100 bacteria will survive. If it’s kept at 60C for four minutes then only ten bacteria will survive and so on.

Each bacterial species, and even strain, has it’s own D values and for species important in our food safety we need to take these in to account when cooking our food. Below are the experimentally derived D values for E. coli, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes, bacteria commonly involved in food poisoning (I got the values from this paper). Using these values we can see that if we want to avoid poisoning our dinner party guests we would need to hold our food at 55C for 27 minutes to kill 90% of any E. coli present, 67 minutes for any Salmonella and 81 minutes for L. monocytogenes. On the other hand the D70 values for the same bacteria are 2.4, 13 and 18 seconds, meaning, for example, any E. coli will be reduced by 90% after holding the food for 2.4 seconds at 70C.

A 90% reduction in bacterial load is pretty good but I haven’t really talked about the specific amounts of bacteria that can cause illness. If, unwittingly, you have a piece of meat that is heavily contaminated with bacteria then a 90% reduction may not be enough to get the bacterial burden to a safe level. In microbiology bacterial loads are normally expressed in terms of colony-forming units (CFU) which, for our purposes here, we can just think of as a bacterial cell count. Although it can vary in different contexts a safe level of bacterial contamination in food is considered to be less than 100 CFU per gram. So if you are cooking to reasonably high temperatures, with the log-fold reductions occurring within seconds, you will be safer because you can burn through several log-fold reductions very quickly. Lower temperatures will result in smaller total reductions for a given time. This is why most health authorities suggest cooking to relatively high temperatures, mostly in the low 70C range for most types of meat.

Now I can almost hear many fans of a rare steak saying “What the hell, I’m not cooking my steak to 74C”. I’m also a fan of rare steak and a rare steak has an internal temperature of somewhere between 49C and 54C. If we look at the D55 values above we can see that few bacteria are going to be killed at that temperature yet I can’t remember ever getting sick from a steak. The reason for this is that the inside of a beef steak is generally considered sterile. Bacterial contamination of beef steak occurs on the surface and the bacteria is unable to penetrate into the muscle. This means that if you give your steak a good seer at very high temperatures, which you want to do to get a nice char from Maillard reactions anyway, then you are usually good1. The official recommendation is still 63C but I’m happy to take the risk that a rare steak presents.

When it comes to ground beef though the scenario changes. Mincing meat drives the surface of the meat into contact with the internal parts of the meat and mixes them all up together. When this happens all of the meat is now potentially contaminated, inside and out. This has ramifications for hamburgers. A lot of people like a medium rare burger but I’m generally a bit wary. Medium-rare is about 54-57C and we can see that even for the most thermally sensitive bacteria, E. coli, you’d need to hold your burger at 55C for 27 minutes to get a log-fold reduction in bacteria. I’m thinking this rarely happens when burgers are being cooked medium rare. If you aren’t sure of the provenance of your minced beef then this starts getting a little risky for my liking; especially if it’s supermarket mince forget about it, I’m going to 70C. Having said that I often have steak tartare at french restaurants so go figure.

Pork, since we got Trichinella spiralis under control2, is pretty much the same story as beef. But chicken is another matter all together. Salmonella and L. monocytogenes are much greater risks in poultry then they are in beef. Moreover, there is some evidence that Salmonella can penetrate chicken flesh and contaminate poultry meat internally as well as on the surface (see here). So not only do we have more Salmonella and Listeria in poultry meat but searing the surface of the meat, like we do with beef steaks, will not save you if there is internal contamination. This is why recommendations for poultry are generally around the 74C range. This temperature is not so bad for thigh and wings, that have much more connective tissue, but it is also the reason that we often experience dry and tough chicken breast. It is difficult to cook chicken breast, which has little connective tissue, to the recommended temperature without drying it out3.

Once food is cooked we can’t relax because bacteria are fond of cooked food as well. Bacteria are all around us, and on us as well, so cooked food can quickly become contaminated with bacteria and then we’re back to the growth dynamics of bacteria. Once the temperature of the cooked food enters the comfort zone for mesophile bacteria we are going to experience log phase bacterial growth. So you don’t want to leave food out for more than two hours because any longer than that and any bacteria lucky enough to get on the food will have passed through the lag stage and be well into exponential growth. You can also see in the graph above that the growth rate for mesophiles is highest around 32C, so if it is a hot day reduce that time to an hour.

You can always reheat leftover food, which is good practice, but in some food stuffs, if left out too long after cooking, bacterial growth causes a build up of toxins that can still cause illness, even after re-heating. The classic example of this is leftover rice. The bacteria Bacillus cereus grows on rice left out for more than a couple of hours and produces the toxins that cause food poisoning. These toxins include cereulide, that causes vomiting, as well as hemolysin BL, non-hemolytic enterotoxin and cytotoxin K all of which cause diarrhea. In this case reheating the rice wont help because it may kill bacteria but it wont destroy the toxins.

I’ve barely scratched the surface of the many food safety issues we should all know about when cooking for friends and family. No doubt I will revisit food safety a few more times yet. But a clear understanding of the way that bacteria colonise and grow on our food is a very good thing for every cook to have. If you ignore the reproductive power of these organisms you will eventually regret it. You wont get food poisoning every time you break the rules but, if you are a serial offender, an inevitable bout of food poisoning will soon instil some bacterial respect, unless you’re dead of course.

Footnotes

- This is also why we can dry age beef, bacteria will only colonise the surface of the steak and when we come to cook it we can just trim off the contaminated outer surface. ↩︎

- The recommendation for pork, until recently, was that it should be cooked to 71C to avoid contracting trichinosis caused by the helminth parasite Trichinella spiralis. I’ll cover trichinosis in a post on parasites. ↩︎

- There are ways though and I’ll cover them in another post ↩︎

Other stuff

Leave a reply to Jason Mulvenna Cancel reply