On October 26, 2015 the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) broke my heart. I know this sounds dramatic and maybe even a little silly. International research agencies don’t go around breaking peoples’ hearts. How can I justify this outrageous statement? Well it was on this day that the IARC issued a press release classifying bacon as a class one carcinogen. A class one carcinogen is something which a panel of IARC experts believes causes cancer in humans1. It wasn’t just bacon either, IARC judged that there was strong evidence linking any meat that has been salted, smoked, fermented or cured to colorectal cancer. So bacon, chorizo, salami, cabanossi, ham and speck; all culinary stars and all class one carcinogens. In a single stroke IARC had put some of my favourite foods into the same category as cigarettes, asbestos and radioactivity.

My first response to this news was denial. I didn’t believe it. I’m a biochemist and I know that the aetiology of gastrointestinal cancer is incredibly complicated with different parts of the gut, microbiome composition and the dietary context all playing important roles. Surely IARC had made a mistake and they’d fix it soon enough. I told myself not to worry it would all come good. At some level I knew behaving like this was wrong. I’m a scientist and I’m supposed to be open-minded and follow the evidence but it was chorizo for God’s sake. So I just went on about my life as if I’d never heard of IARC. Amazingly, I managed to pull off these mental gymnastics while literally working in a medical research institution as a cancer researcher.

But once you know you can never forget and, over time, the cognitive dissonance got the better of me and I got angry. Why should I feel guilty every time I ate a ham sandwich? Haven’t humans been eating processed meats for thousands of years? What the hell am I supposed to do without bacon? Why does everything but celery give me friggin cancer? Anger is a great motivator so I decided to do some reading. I wanted to look at this so-called evidence myself. Probably all observational studies full of confounding factors with no mechanistic evidence whatsoever, I thought. Just how strong could this ‘evidence’ be anyway? Sadly, it turns out it was pretty strong.

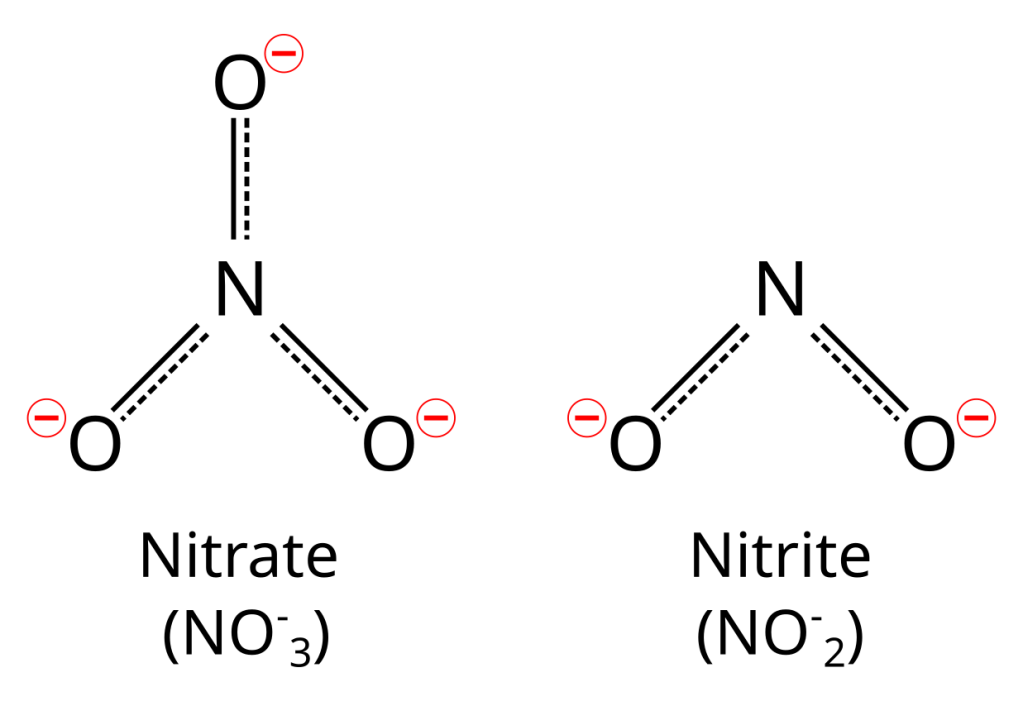

The association of processed meat with colorectal cancer is the story of how two molecules, nitrate (NO3–) and nitrite (NO2–), are chemically modified and broken down during curing and in the gut after consumption. Nitrate has been used for curing and preserving meat for, at least, centuries in the form of saltpetre. Saltpetre, also a major ingredient of gun powder, is just a salt of nitrate and potassium (KNO3) or sodium (NaNO3, known as Chile saltpetre). When used for curing meat most of the nitrate in saltpetre is converted to nitrite and it is this molecule that inhibits bacterial growth, prevents spoilage and contributes to the characteristic pink colour of cured meats. These days commercial curing usually uses sodium nitrite instead of saltpetre, although saltpetre is still occasionally used, especially for traditional products.

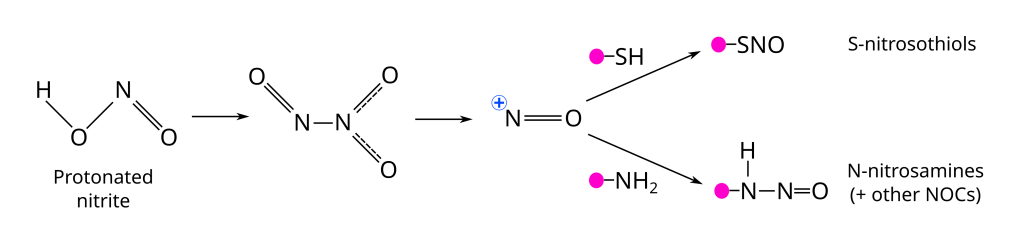

There is a lot of chemistry that goes on when we eat food containing nitrates and nitrites and I can’t, or more accurately don’t want to, cover it all here. What I do want to do is build a simplified model of the chemistry that will help us understand why processed meat can cause cancer. So lets get this small amount of chemistry out of the way. In the acidic environment of the gut nitrite will exist in the protonated form HNO2. The protonated nitrite can react with other protonated nitrite molecules to form N2O3 which will, also because of the low acidity, release the nitrosonium ion (NO+). The nitrosonium ions then react with different chemical groups on protein fragments. This reaction can produce a few different types of molecule depending on which chemical group on the protein fragment the NO+ reacts with but the two important ones for us are S-nitrosothiols, which form with protein thiols, and N-nitrosamines, which forms with protein amine groups.

What we really want to see here is the production of S-nitrosothiols because these molecules, along with nitric oxide (NO), have important and beneficial roles in cardiovascular and metabolic health. So it is good that in the acidic environment of the gut S-nitrosothiol is the favoured reaction. But sometimes when there are a lot of nitrite molecules in our gut, like when we have eaten processed meat, the production of N-nitrosamines, along with similar molecules collectively called N-nitroso compounds (NOCs), can increase. This is not such a good thing as N-nitrosamines and the other NOCs are well known carcinogens.

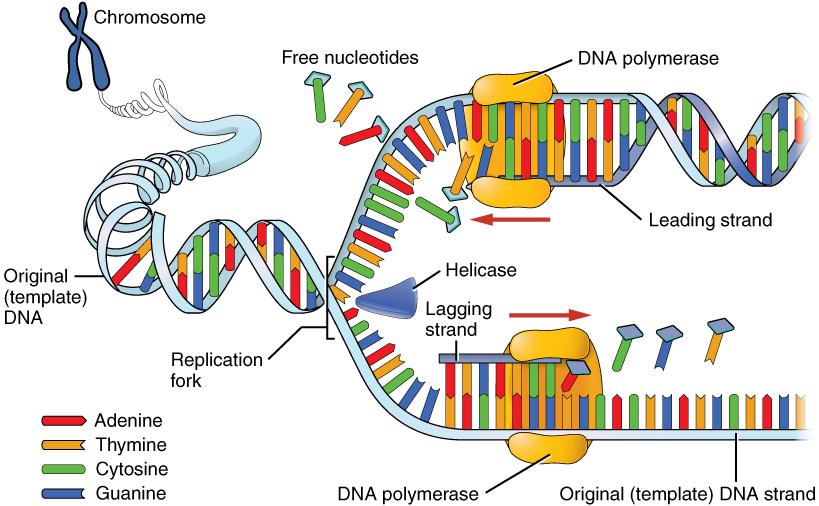

The carcinogenic activity of N-nitrosamines stems from their ability to add a a chemical group called an alkyl to our DNA. This is important because over the course of a day the human body will produce about 330 billion new cells. These new cells are produced in a process called mitosis where a single cell splits in half and produces two new daughter cells. Every time this happens all the DNA in the nucleus of the cell needs to be duplicated so each of the daughter cells receives a full complement of DNA. To do this the cell has a complex and normally very effective DNA replication machinery. During mitosis DNA unwinds (it’s a double helix remember) and various enzymes whip along each strand producing a new strand with matching base pairs which results in two copies of the original DNA.

Problems arise when N-nitrosamines, and the other NOCs, add the bulky alkyl group to our DNA. The unexpected chemical group interferes with the DNA replication machinery and you can get errors in the DNA code that are passed down to the daughter cells. If you get an error in the wrong place, if it disrupts proteins important for controlling cell growth for example, you can end up with a mutation that causes the cell to become cancerous. Ultimately, this is how processed meats are able to cause gastrointestinal cancer. NOCs produced from nitrites cause mutations in the DNA of your cells that can lead to cancer.

As I said above, I have greatly simplified the chemistry and there are other influential factors like the microbiome, what part of the gut you are in and the dietary context2. But even this simplified version is pretty compelling, and it is backed up by lots of experimental evidence. It seems I wont be proving IARC wrong as easily as I (stupidly) thought I might. But, there are still some nagging questions. One of them is what about other foods that are rich in nitrates or nitrites? Fresh fruit and vegetables have a ton of nitrates, in particular, and a lot of those nitrates are converted to nitrites by bacteria in your saliva. So why are diets rich in vegetables and fruit associated with a low cancer risk when they are packed with the same molecules that cause cancer in processed meats? Why isn’t a cabbage a class one carcinogen? Unfortunately this is not a big hole in the theory, but to understand why vegetables aren’t carcinogenic we need to develop our working model a little bit and consider the role of proteins in the NOC production described above.

Firstly, fresh vegetables have a lot fewer protein fragments than processed meat. During curing and fermentation not only does a lot of nitrate get converted to nitrite but a lot of protein also gets broken down into fragments. As we saw above these are good conditions for the formation of NOCs so our processed meat product is going to have a bunch of pre-formed NOCs in it before it gets anywhere near our mouth. This means that when we eat the processed meat we will not only produce NOCs from the nitrites in our gut but we will also get a healthy dose of pre-formed NOCs that can get to work on our DNA straight away. Fresh produce, on the other hand, has a lot less protein fragments, the proteins are intact, and they also don’t have bacteria converting nitrate to nitrite. Without much nitrite or the protein fragments for it to react with conditions aren’t right for NOC formation. Because of this fresh produce has almost no pre-formed NOCs when we eat them.

Fresh produce also doesn’t stimulate the production of NOCs when they get to our gut. One reason for this is that a molecule called haem also seems to be required for the production of NOCs from nitrite. Haem is an iron containing molecule that is able to bind oxygen and it is famous for it’s role as a part of haemoglobin, the protein that transports oxygen around our circulatory system. Skeletal and muscles cells are also rich in haem because they use a related protein called myoglobin to store oxygen. So processed meat has plenty of haem and it reacts with NO+ to form a molecule called nitrosylated-haem which is actually the molecule that goes on to react with protein fragments and form NOCs. When considered this way, it seems to me that it is haem that is driving NOC formation rather than nitrites, which might be important when I look at red meat in a future post. Either way, haem is part of the reason that fresh produce doesn’t stimulate NOC production, no fruit or vegetable contains haem.

Another reason fresh fruit and vegetables don’t stimulate NOC production in the gut is that they are packed with molecules called antioxidants. Antioxidants are molecules that are able to neutralise other highly reactive molecules. Antioxidants found in fruit and vegetables, like polyphenols, vitamins C and E and anthocyanins, can inhibit the production of NOCs by neutralising reactive nitrogen species, like N2O3 and NO+ that we discussed above, preventing them from reacting with haem and so preventing NOC production. If you are wondering if this means we can eat lots of vegetables with our bacon and we’ll be fine? The answer is probably no. The antioxidants may prevent NOC formation in the gut but they can’t do anything about the pre-formed NOCs that you get when you consume processed meat. Eating vegetables is the path to good health but they can’t save you from dietary NOCs in processed meats.

Alright I’m convinced and I need to accept that processed meats are not that good for me. But what are the risks? Am I doomed to a short life dying with a cancer-riddled gastrointestinal tract because of my love of charcuterie? Well here the story gets a tiny bit better. There are a lot of observational studies on processed meats so the statistics vary from one paper to another. But taking one, essentially at random, it reports a relative risk of 18% for colorectal cancer. We all know now that relative risk is not absolute risk and so we want to get an absolute risk. Working with Australian data, 1 in 21 people (about 4.8%) will develop colorectal cancer by age 85. So an 18% increase in relative risk means the absolute risk will go up to 5.7%, a 0.9% increase in your chances of getting colorectal cancer.

This is real back of the envelope stuff because my baseline includes people who ate processed meats anyway but a 2005 UK study found that the ten year absolute risk for colorectal cancer went from 1.28% to 1.71% between the lowest and highest consumers of red and processed meats. Personally, I don’t think these are huge increases in absolute risk and the World Health Organisation agrees. But this is my assessment, everyone has a level of risk that they are comfortable with and others may be at particular risk if they have a history of colorectal cancer in the family. Processed meats have also been associated with a range of other cancers so, even if you are comfortable with a low absolute risk of colorectal cancer, the cumulative risk of other cancers may get you thinking about how much processed meat you are eating.

Which is a good question. If I’ve accepted that processed meats can cause cancer how much processed meat should I be eating? If I’m going to stop gorging myself on cabanossi every day how much gorging can I get away with? Well the bad news is most advisory bodies recommend not eating processed meat at all. The epidemiological evidence suggest that there is a dose-response relationship so the more processed meat you eat the greater the risk and the WHO estimates that each 50g daily serving (about two bacon rashers) of processed meats increases the risk by 18%. This is, again, a relative risk equating to around a 1% increase in the absolute risk if we use the above rough calculations.

We all need to decide how we want to behave and what level of risk we want to accept. I can’t give advice on how you should behave but I’m not going to stop eating processed meats completely. I’m certainly going to eat less processed meats. I don’t need to eat bacon everyday and I’m willing to treat processed meats as a ‘sometimes food’ and have a couple of servings a week. There is some evidence that diets high in fibre can mitigate the risks of processed meats (see here) so I want to eat more vegetables, beans and fruits. Other risk factors for colorectal cancer are obesity, a sedentary life style and alcohol so avoid fattier foods, exercise and drink less. Really we’re back to where we always get to when thinking about diet and health. Eat a well balanced diet with plenty of fresh fruits, vegetables, nuts, and grains, enjoy the odd steak or charcuterie board and we’ll probably be fine; we’ll certainly be healthier and better able to enjoy whatever amount of life we end up getting.

Footnotes

- The other categories are 2A “probably carcinogenic”, 2B “possibly carcinogenic”, 3 “Not classifiable” and 4 “probably not carcinogenic”. There is not a lot of joy in IARC classifications, the best you can do is “probably not carcinogenic”. ↩︎

- If you want to learn more start here, it’s behind a paywall but it is on SciHub. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Gary Cancel reply