Are you confused about what we should be eating? Bewildered by contradictory dietary advice? Overwhelmed by dietary fads and loud-mouthed influencers? Well you are not alone. Over the past five decades endless cycles of contradictory nutrition advice and dietary fads have left most people in a state of utter confusion about what constitutes a healthy diet. And it seems to be getting worse not better. This year we saw the Health Secretary of a major country sitting in a fast food joint extolling the virtues of beef tallow over plant oils, is he right? Probably not but who knows? All it really achieved was to spark another ferocious food controversy. If nothing else it is exhausting. I’m sick of feeling guilty if I have a glass of wine and tired of feeling like a criminal if I add some butter to the family dinner. I’ve had enough.

Take something like alcohol. A simple Google search for ‘is alcohol good for me’ will tell you that no amount of alcohol is good for you but also that moderate drinking is good for your heart health. It is not just the internet though. The scientific literature is equally confused. Study after study offers contradictory results about salt, red meat, alcohol, eggs and anything else we humans consider food. One could start thinking that scientists don’t have a clue and, frankly, I think you would be right for thinking so. I’m a scientist and I don’t think scientists have a clue about nutrition at the moment. I also think that the mess in nutritional science is the poison well from which our food confusion springs. So in this post I want to go through some of the scientific practices that I think are contributing to this situation and in doing so hopefully provide some pointers on how to interpret the science and help you make up your own mind about some of these issues.

Lets start with the way that most nutrition studies are conducted. The classic conception of a scientific experiment is one that is performed in such a way that the only thing that is varied is the thing you are testing. A simple example would be an experiment to see whether carrots grow better on Coca Cola rather than water. All you have to do is grow two groups of carrots under the same conditions but water one group with Coca Cola and the other with water. After some time you could just weigh the carrots and see which group had produced the most carrot mass. This is called a controlled experiment; an experiment in which there is a dependent variable, the weight of the carrots, and an independent variable, Coca Cola or water.

So, say we want to conduct a nutritional study on how saturated fats affect our mortality. Could we randomly select some new-born babies, lock them in a compound, raise them exactly the same way but feed one group on a diet with saturated fats and one group with no saturated fats and wait and see at what age they all die. No, of course we cannot do this. Although it is attempting to be a controlled experiment, ethically it is a horror show, it would be extremely expensive and all the original scientists would be dead of old age (or heart attacks from too much bacon) before the study even concluded.

In nutritional studies the closest thing we have to this is something called a randomised clinical trial (RCT). In a RCT we would randomly select a control and a test group then administer saturated fats to the test group and a placebo to the control group and monitor the participants health over a defined period of time. Preferably the study is double blinded, that is neither the participants or the researchers know which group a specific participant is in, and it is also prospective, that is the participants are followed forward over time and various dependent variables measured periodically; blood pressure, cholesterol levels and weight for example. This type of study is considered a gold standard in nutritional studies because the random selection of participants, hopefully, distributes any confounding factors (more on these below) equally across both groups and double blinding reduces bias and might reduce placebo effects that could influence the results.

So, you might be thinking, lets just use RCTs and sort out all this nutritional confusion. Well it’s not that easy. Firstly, an RCT might be good for say a drug that is meant to lower blood pressure over the short term. You can run the trial, measure blood pressure as the dependent variable and run the trial for a short period of time. With nutritional studies though we want to know if a particular diet is good over a long period of time, potentially decades, and these studies are enormously expensive to conduct. We also can’t lock the participants in a prison and make sure they haven’t started smoking, suddenly become a jogger, experienced unusual stress or done anything that comes with having a life. Participants will often drop out of long running studies and we also can’t be sure that they are keeping to a specific diet. We also can’t do anything that isn’t ethical, if we wanted to look at the effects of heavy drinking we couldn’t force people to start drinking a bottle of whisky a day. There are a lot of challenges when we want to use this kind of study to look at nutrition (and I’ve just touched the surface if you want to get in the weeds this is a good place to start).

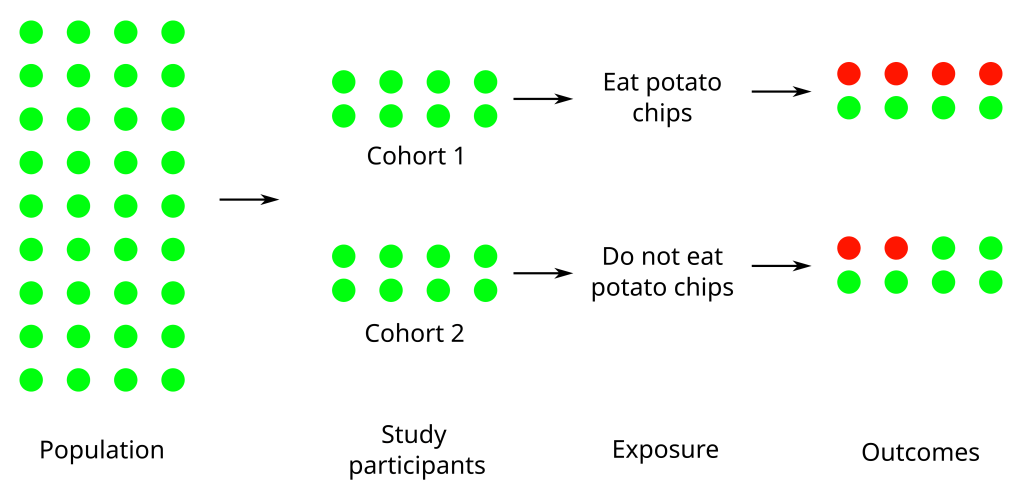

So, what normally happens is that researchers fall back on what are called observational studies. An observational study has no researcher intervention at all, the researcher simply observes a group of individuals and records outcomes. There are a couple of different types of observational studies so lets take an example, say a researcher thinks that potato chips causes high blood pressure, and design some simple experiments. The first one could be a prospective cohort study. In this type of study a group of people is selected and then followed over time. Periodically, the researcher will meet with the participants and ask them about their potato chip consumption and measure their blood pressure. Over time as people develop high blood pressure you can correlate their potato chip consumption with their blood pressure. Alternatively, you could have a test and control cohort, people who eat chips and people who do not eat chips that you would treat the same way.

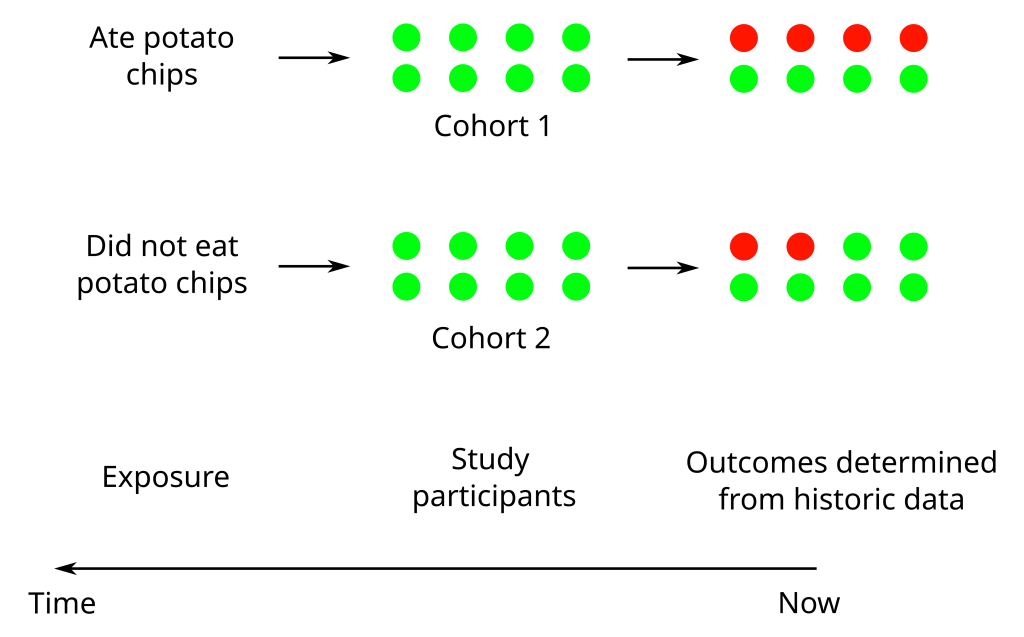

Now lets say you hear about a nursing home that is really cost-conscious and it’s accountants have been recording what everyone in the home ate for the past 20 years. Being a nursing home they are also keep medical records. You are now in a position to conduct a retrospective cohort study. You can use this data that has been ‘pre-collected’ for other reasons, tease out the potato chip consumption from the overall food data and assess it’s relationship to blood pressure by looking at the medical records. Finally, in a cross-sectional study you can just select a group of people and ask them how many potato chips they have eaten over their lifetime, measure their blood pressure and use that data to construct a statistical model relating potato chip consumption to blood pressure.

I have greatly simplified things here but it is enough to see how observational studies aren’t generally considered solid evidence on the level of an RCT. Firstly, observational studies can be constrained in how they select their participants. In a retrospective study you are constrained by what data is available, elderly people in a nursing home for example. In a cohort study your test and control groups are dictated by the participants, have they ever eaten chips or not. Depending on your study this may introduce sample bias that restricts the general applicability of your results. The retrospective study on nursing home residents, for example, would really only be applicable to elderly people because the only data you have is from when the people were in a nursing home.

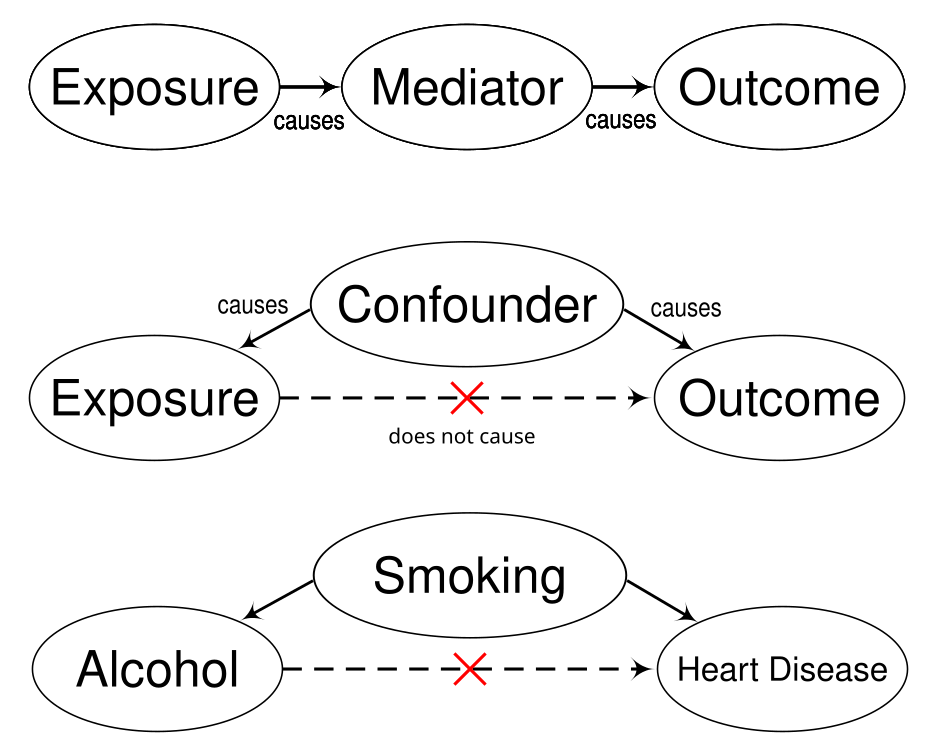

More serious is the problem of confounding factors, a factor that influences both the independent and dependent variables and can lead to a spurious association. A classic confounding factor is smoking when looking at the effects of alcohol on heart disease; smokers are more likely to drink alcohol so if you don’t control for smoking then alcohol will be associated with heart disease not smoking. Observational studies are susceptible to confounding factors because randomisation is often not possible. In our potato chip example, because our test and control cohorts were selected on the basis of whether they ate potato chips or not, they aren’t randomised. It is quite possible that people who don’t eat potato chips exercise more. So in our study a finding that potato chips cause high blood pressure is actually confounded because the real cause of high blood pressure is the lack of exercise not the potato chips.

Although there are strategies for dealing with confounding factors they are still a huge problem for nutritional observational studies. You need to know about possible confounding factors to be able to handle them and they can be difficult to identify. For example, recent discoveries about the gut microbiome are a massive confounding factor for older nutritional studies where researchers didn’t know much about the microbiome or it’s effects on our health. Likewise, many studies focus on a single type of nutrient, say omega-6 fatty acids, and completely ignore the synergistic effects of a complete diet which introduces a whole host of potential confounding factors to be found in the overall dietary context.

Another major problem for these types of studies, especially retrospective ones, is they can rely on self-reporting by participants and unfortunately humans can be parsimonious with the truth. Participants in alcohol studies, for example, may be susceptible to under-reporting their actual alcohol consumption (see here for a paper with some discussion about this). No one wants people to know how much they drink, including myself. Apart from this people are forgetful and they are hesitant to report things they think will be judged. More damaging is the misreporting by those at the extremes of a group. Under-reporting of energy intake increases with body mass index and under-reporting of alcohol intake increases in heavy drinkers (see here for alcohol and here for BMI). That is the more overweight someone is the more they will under-report what they eat. I imagine at the other end of the scale people with border-line or full blown eating disorders will over-report their food intake. Likewise people who know they are at risk of a heart attack may not ‘confess’ to indulging in dietary options they think are not appropriate. Any observational study that relies on self-reporting may have problems with it’s data and so it’s conclusions.

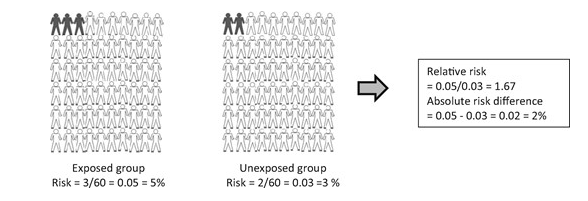

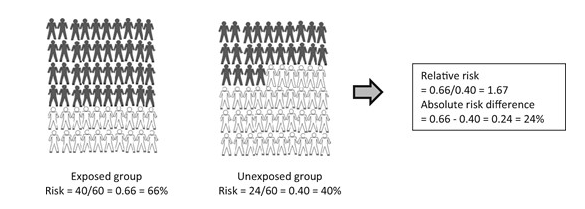

From a non-scientist perspective the way that results are reported may also lead to a distortion of the perceived risks behind certain foods. Scientific papers routinely report something called a relative risk, or similar measures such as an odds ratio or a hazard ratio. The thing about these measures is that they are quantifying a difference between groups, usually the control and the experimental group, and not the absolute risk. For example, say it is reported that the relative risk of getting some hypothetical cancer for a moderate drinker is 1.17 when compared to a non-drinker, i.e a 17% greater chance. That would get most people’s attention. But if the base line of people who get this cancer is, for easy maths, 10 in 1000. This means that for moderate drinkers 11.7 people per 1000 will get the cancer. So your absolute risk has gone from 1% to 1.17%, i.e. a 0.17% increase. In this hypothetical example a moderate drinker still only has a 1.17% chance of contracting the cancer. In short, a large percentage of a small number is still a small number (here is a slightly partisan article that goes through actual absolute risks for several different foods).

Given all the drawbacks of observational studies I set out above this tiny effect would not be a compelling reason for me to give up my Saturday afternoon beers. Relative risk provides an easy way to summarise a difference between groups but without a baseline risk it can be hard for someone, especially a non-scientist, to assess what that means to them as an individual. If you are a cynic you could also suggest that some very small effects can be made to appear more interesting using the relative risk when you are trying to get something published.

Getting things published also brings us to the problem of p-value hacking. Whenever you see difference between the two groups, like a test and control group, you need to run some statistical tests to work out if the differences you see are real. We need to do this because almost always scientists are dealing with a subset of a population. If you are testing a new drug you could give it to everyone in the world, see what happens and you wouldn’t need statistics. This is obviously not feasible so almost all studies revolve around a sample of people that, hopefully, represent the general population. If you observe a difference between your sample groups the p-value is a statistical measure that tells you the probability of your effect not being reflected in the greater population. That is the probability that you have observed a false positive (what statisticians call a Type I error). Scientists generally consider a p-value of 5% a reasonable cut off for considering a result to be real. But it’s important to realise that this is just an arbitrary cutoff, we could just as easily as settled on 1% but convention is that a p-value of 0.05 is considered worthy of publishing.

The problem is that now we have a metric for deciding if a result is real everyone wants to make sure that their study reaches this threshold so they can get their work published. There are a bunch of ways that you can manipulate your data to achieve a significant p-value and this is what we call p-value hacking. Some are relatively benign and some are verging on outright fraud. Researchers can analyse data as it is collected and then stop when they get a significant result (an appropriate sample number should be determined before the experiment) or they can remove outliers that are ‘distorting’ their data. Variables can be manipulated and data sliced and diced into different subsets or continuous variables can be converted into discrete variables (something like time data can be combined into time buckets that groups results over a certain time period).

Another common method is to change hypothesises mid-study, the researcher takes a peek at the data and decides that a different outcome will provide a significant result so they change the study goals. Finally, a data set can be tested many different times until a significant result occurs. Remember that the p-value gives a probability that your result is real when in fact it isn’t, so the more tests you do the more likely it is that you will stumble upon a significant result. There are statistical corrections you can make when you are performing multiple tests and when I was routinely reviewing papers it was probably my number one criticism, that a multiple testing correction be made to results. The enormous pressure scientists have to publish and p-value hacking has led to a bit of a crisis in some scientific fields. Nutritional studies with it’s reliance on observational studies is one that has been impacted. One famous example is someone like Brain Wansink who gained fame with some creative studies on food that ended up being the result of some even more creative analytical methodologies (there is a good write up about him here).

When you combine a reliance on observational studies, lack of randomisation in study design, confounding effects, a historic culture of p-hacking, small effects and other things I haven’t talked about (industry sponsored research and publication bias for example) you can start to see why some would think that almost nothing of use has come out of nutritional science. Even worse is that the availability of scientific ‘evidence’ for almost any nutritional viewpoint makes evaluating competing claims very difficult. Processed food companies, those selling dietary fads, the media, doctors, governments and any one with a stake in what we eat can all make claims partially backed up by scientific evidence of some sort. Nutritional science will hopefully clean up it’s act, break it’s reliance on small observational studies and adopt some better practices in generating nutritional knowledge. In the meantime, for non-scientists, the best remedy is to question anyone telling you that they know anything about nutrition and learn some basic skills for evaluating scientific evidence. In a world where everyone seems to be beating a drum of some description these skills might come in useful in other areas as well.

Leave a reply to Jason Mulvenna Cancel reply