When considering the great florescence of thought and ideas that was the Enlightenment we tend to focus on the big ideas, the big innovations and the big thinkers like Voltaire, Locke and Adam Smith. But, as in any other time of great intellectual or technological change, there are other, smaller, ideas that fly under the radar of history. Ideas that are inspired, perhaps, by the intellectual currents of the day but are nonetheless considered too mundane, too common place to be recorded in history. Not such a problem these days, where the minutia of everyday life is recorded in excruciating detail on social media1, but throughout much of history small innovations percolated through a culture, passed orally from one person to another, invisible to history.

Until recently cooking was one of these fields of human endeavour that bubbled away below the surface of history. We eat everyday but the history of food was not usually deemed worthy of scholarly attention. The domain of homemakers, usually woman, or professional chefs who, if they wrote anything at all, spoke to fellow chefs assuming a great deal of prior knowledge2. The history of our food often comes down to a passing reference in written works on other topics or some depiction of food production in a painting, sculpture or frieze. We have no record of the development of some of our most common dishes or culinary techniques. New dishes or techniques just seem to appear in the historical record, not quite fully formed perhaps, but pretty close.

Using egg whites to create a stabilised foam is one of these culinary techniques that seemed to just pop into existence. Early in the Enlightenment period, in the late 1600s, it appears that chefs worked out that prolonged whisking of egg whites produced a relatively stable foam that could be used to make things like souffles, meringues and mousses. Sure people had been using eggs to thicken things for a long time, the Romans and the Egyptians had made a crude form of nougat for example, but whisking eggs into a foam that could be cooked, as in meringues, or incorporated into other mixtures to provide a delicate, airy texture was a brand new thing.

Why this happened in the late 1600s we aren’t too sure. It is hard to properly whisk eggs without the proper equipment, a fork or whisk for example, and prior to this coarse foams had been created using things like twigs. The key innovation seems to have been the use of bundles of straw as a whisk that allowed for a prolonged and efficient whisking of egg whites to create a stiff foam. We’d had straw for a long time before this though, so why this didn’t happen earlier? Who knows? Maybe it was just the spirit of experimentation that infused the Enlightenment. But happen it did and now we have souffles, mousses, meringues, macarons, pavlovas and many other dishes that rely on the unique chemistry of egg whites that enables them to create foams.

If you agitate some some water, shake it or whisk it, you can briefly see bubbles of air appear in the water but they quickly rise to the top and escape into the air. This is because water has a high surface tension, water wants to interact with water so air is quickly excluded. To create a foam you need something to prevent the air from interacting directly with the water, not too dissimilar to emulsifying oil in water, but you also need structure to trap the air bubbles in the liquid and allow the foam to maintain its shape.

We’ve actually already looked at one foam, whipped cream, where partially disrupted milk globules interact with air and each other to build structure around air bubbles, trapping them and stiffening the foam. Whisking egg whites into foam is a similar process but instead of milk globules the emulsification and structure is derived from the proteins of the egg white.

One of my first posts was on how to fry an egg and when you whisk egg whites into a foam you are doing something very similar to frying an egg. When you fry an egg the heat causes the proteins in the egg white to unravel or, as it’s technically known, denature. Most proteins have a three-dimensional structure where hydrophobic (water fearing) amino acids form the core of the protein, interacting with each other, while the water-loving hydrophilic amino acids are exposed on the surface where they interact with water3. When the proteins unfold they expose their hydrophobic core and they start interacting with each other, forming a network of cross-linked proteins that traps water and causes the egg white to solidify. The longer the egg is cooked the tighter the protein network becomes.

The same process occurs when we whisk egg whites but, instead of heat causing the proteins to denature, it is the physical abuse of the proteins that causes them to denature. At the same time the whisk is forcing air into the mixture. The exposed hydrophobic core of the denatured egg proteins ‘prefer’ to interact with air so gradually the proteins organise themselves so that their hydrophobic parts are exposed to the air bubbles and the hydrophilic parts are interacting with water. The denatured proteins are also interacting with each other building a network of interacting proteins that provides structure and traps water, just like a frying egg. This protein network is the scaffolding that stabilises the air bubbles and causes the foam to thicken.

The longer the whites are whisked the more extensive the protein network becomes, the more water is trapped and the firmer the foam becomes. This gradual build up of structure allows us to control just how stiff we want our foam to be. At the soft peak stage there is still ample water that hasn’t been captured by the growing protein network which provides lubrication for stabilised air bubbles to slide past each other. But as whisking continues the increased structure captures more and more of the free water. By the stiff peak stage most of the water has been captured and the air bubbles are held in place by the now extensive protein network. There is also no water between the foam and the bowl meaning the protein network can cling to the bowl, leading to the infamous test for stiff peaks where the bowl containing the foam is held upside down over your head.

If you keep whisking the protein network tightens to the extent that it starts to squeeze out the water and the foam splits and becomes grainy with coagulated protein and you have an over-whipped foam. Which stage you want to get your foam to is a function of what you are going to use it for. The stiffer the foam the harder it is to incorporate into something else so for things like souffles and mousses you probably want a softer foam while something like a meringue, which is normally an element in and of itself, you probably want a much stiffer foam with plenty of structure. There aren’t many uses for over-whisked egg whites but adding another egg white and gently whisking might re-emulsify the mixture.

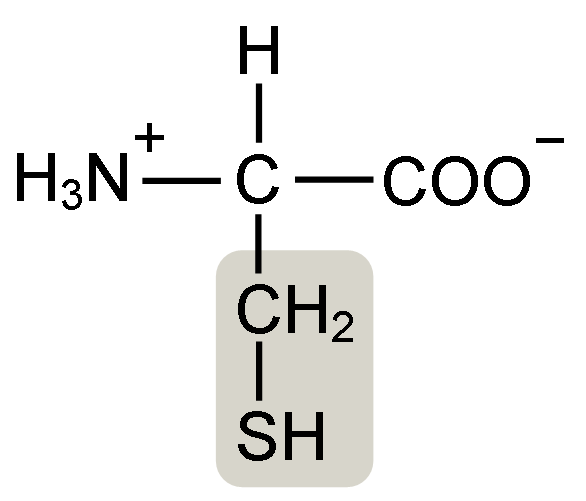

You can also make it harder to over-whip your egg whites by taking advantage of an old French tradition of using copper bowls. Though it may seem a little fantastic copper bowls can, and do, prevent over-whipping because of the role cysteine amino acids play in protein interactions. Cysteines are amino acids that have a side chain that is terminated by a thiol group, a sulphur bound to a hydrogen atom (-SH). Cysteine is a weak acid, meaning it can donate a proton (a H+ ion) to another substance, in water this means that the thiol group is often without the hydrogen atom freeing the sulphur atom to form a disulphide bond with another cysteine residue. The other cysteine residue can be on the same protein or on another protein, either way it cross-links a protein to itself or another protein more strongly than any of the other forms of protein interactions.

A characteristic of copper atoms is that they bind tightly to free sulphur atoms, preventing them from reacting with any other molecules. So in a copper bowl, tiny amounts of copper end up bound to cysteine residues in the proteins of the egg white. This blocks the formation of disulphide bonds and effectively removes one of the ways that the proteins can interact. Without these bonds it is more difficult to over-whip egg whites because the proteins cannot form the very tight network that causes the foam to split. Adding small amounts of copper powder to the whites also works as do silver bowls, if you can afford it4.

Acid will also help prevent you over-whipping your egg whites. Because cysteine is a weak acid if there are a lot of other H+ ions floating around then it becomes harder for the thiol group to lose it’s H+. Acidity is really just a measure of the H+ ions in a solution and a low pH means there are a large number of them floating around. In these conditions the thiol groups on the cysteine residues will not be able to lose their H+ and so wont be able to form disulphide bonds. How much acid? Harold McGee recommends adding 2ml lemon juice per egg white to the mix before starting to whisk.

As much as we don’t want to over-whip our foam we still want to be able to form a foam and, if whisking manually, as quickly as possible thank you. Salt is one thing that will maker it harder to form a foam. Salt, composed of sodium ions (Na+) and chloride ions (Cl–) interacts with the charged or polar parts of a protein that would otherwise be interacting with other proteins. The interactions that salt inhibits, hydrogen and ionic bonds, are very important for protein interactions and removing them makes it very hard to form the protein scaffold and so a stable foam.

Sugar also makes it harder to form a foam, which can be a problem when making meringue, a sweetened egg white foam. Sugar slows the denaturation of the egg white proteins and so slows the formation of the proteins network. Adding sugar before starting to whisk makes it significantly harder to get a firm foam. This isn’t a problem if you have an electric mixer, or you are wanting to get some exercise manually whisking, but it also makes for a heavier, fine grained foam. This is because sugar also increases the viscosity of water making it harder for it to spread out into walls around the air bubbles.

Once a foam has formed though sugar can act as a stabiliser. Because of the increased viscosity it reduces the amount of water that leaks from the foam over time. If you cook the foam, which you often do with meringues, sugar will also add more structure because it forms solid dry strands of sugar, which also makes the meringue crispier. For these reasons, when making a meringue, sugar is usually added after some structure has formed, though a heavier, sugar at the start, meringue is used for some applications.

Finally, the golden rule in whipping eggs is keep anything that is happy at the air-water interface out of the mix. If you remember from the emulsions post, something like a fatty acid will have it’s hydrophobic part toward the air and it’s hydrophilic part in the water. The problem when trying to build a foam is that they don’t add any structure because they don’t cross-link with the proteins. This makes it much harder to achieve a stable foam and if you have too many of these molecules you wont be able to form a foam at all.

Oils and fats, although they aren’t emulsifiers, will also want to congregate at the water-air interface precluding proteins and preventing the formation of structure around the air bubble. They will also interact with the exposed hydrophobic cores of the denatured protein stopping them from interacting with each other. We know that egg yolks are not only packed with fats (triglycerides and cholesterol) but they are also packed with emulsifiers both of which will congregate at the air/water interface. This makes egg yolk fatal for the formation of a foam from the egg whites. The yolks are also the most likely contaminant so be careful when separating your whites from your yolks if you plan on making a foam.

That’s it for egg whites, for the moment anyway. There is more science behind meringues, souffles and mousses that can be useful so I will do some short posts on each of these dishes in the future. Though most of this science is still an extension of the basic idea of forming a stabilising protein network to trap air bubbles and give structure to your foam. In the meantime happy whisking and thank those Enlightenment chefs for improving on the twig for foaming our eggs.

Footnotes

- Assuming that future generations have the technology to read the data on our hard drives. ↩︎

- The exception proving this rule is the 1000 page illustrated cookbook published by Bartolomeo Scappi in 1570. This was the first illustrated cookbook ever published and it was a runaway success. Scappi was way ahead of his time; you could say he invented fusion combining, as he did, different culinary traditions into elaborate dishes. But it wasn’t until the 18th century that other chefs caught up and started thinking about their business in the same way Scappi did. If you want to read more there is a good article here. ↩︎

- If you need some background on this there is a quick primer here. ↩︎

- This was worked out by Harold McGee of “On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen” fame. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Anna Cancel reply