Imagine you are driving down a long and lonely highway. You are late but also conscientious, so you want to stick as closely to the speed limit of 100 km/h as you can. For the purposes of this story your cruise control is broken or you don’t don’t trust Tesla’s self driving function so you want to control your speed yourself. So when your speed decreases you tap the accelerator and when it exceeds 100 kph you take your foot off or touch the brake. If a hill comes along you accelerate going up and brake going down. By monitoring the speed and constantly readjusting to keep it within a a defined range you have selected a set point and you are making adjustments to keep your speed as close to that set point as possible, regardless of external influences.

In biology this process of keeping a constant speed on a lonely highway would be called homeostasis. Homeostatic processes in the body are those that seek to keep a certain parameter at a set point by monitoring the parameter and correcting when it moves away from that set point. It is a really simple concept but when you start thinking about homeostatic processes you start seeing them everywhere.

In biology and physiology, although it resonates with ancient Greek ideas of internal balance and equilibrium, it took scientists a little while to catch on, as is so often the case. The first person to really link health with the maintenance of internal stability was the french physiologist Claude Bernard around 1865. But it took another 50 years or so before his ideas were really embraced and the importance homeostasis was recognised.

Once it was recognised it was impossible to ignore. The human body regulates an enormous number of internal parameters in the course of it’s normal operation. Temperature is an obvious one but things like blood pressure and pH, fluid balance, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, hormones and ion concentrations are all maintained using homeostatic processes. Accordingly a large number of diseases are now seen as failure of homeostasis. Diabetes, obesity, osteoporosis, high blood pressure, Alzheimer’s, various autoimmune diseases and even addiction are all now viewed, at least partly, as a failure of homeostasis.

On a daily basis we don’t really think much about all these processes keeping us healthy but some do have a direct impact on our consciousness and behaviour. We put on jumpers and take naps in direct response to homeostatic processes making us feel cold or tired. But the homeostatic process we are probably most familiar with is hunger. Everyday we get hungry and we stop this discomfort by eating. Some of us also spend a lot of time struggling against our hunger drive, that is we diet. A struggle that can manifest as something as minor as excessive complaining to dangerous diseases such as bulimia and anorexia. Recently, with the advent of GLP-1 receptor agonists, we have started treating diseases such as diabetes and obesity with medications that are copied directly from our hunger feedback loop.

At a conscious level hunger is just one of stage of our experience throughout a day. Hunger, of course, is the desire to eat, a desire that will grow until we do eat. As we eat we start to experience a feeling of fullness and when we are satisfied we stop eating. This is called satiation; the stage where we are loosening our belt and talking about being in a food coma. After we have recovered from satiation we go through a stage where we aren’t really thinking about food at all, we aren’t experiencing satiation anymore but we also aren’t that hungry. This is called satiety.

Our progression through these stages is actually the result of several different, but connected, homeostatic processes, the contributions of which all sum to how we are feeling about eating at that particular moment. I’ve actually already covered one of these in the post on ultra-processed foods. The regulation of blood sugar levels is a homeostatic process that can contributes to how hungry we feel. But there are others that are just as important.

The first of these is called gastric accommodation and it is a feedback loop meant to keep gastric pressure low. If our gut was just a solid inflexible tube then eating would inevitably increase the pressure in our gastrointestinal tract, like water going through a hose. This increased pressure would force food quickly through our gut making it hard to digest properly, not to mention the dire consequences that would follow when a high pressure stream of partly digested food reached the end of the tube. Gastric accommodation is what controls gastric pressure and saves us from these consequences.

When we start eating our stomach expands acting as an initial safeguard against increased gastric pressure. It is a pretty effective safeguard, our stomach can stretch up to 15 times it’s normal volume without increasing gastric pressure. But there is a limit and when the stomach has stretched as much as it can we start to experience feelings of fullness that increase our satiation and make us stop eating.

The stomach’s ability to expand means it is acting like a dam during heavy rain. Just as the controlled release of water from a dam can prevent flooding downstream so the stomach can gradually release food into the intestine without increasing gastric pressure. Just like managing a runoff from a dam this release, called gastric emptying, needs to be carefully orchestrated and even before the stomach has reached it’s maximum capacity the body has started preparing for the passage of the food from the stomach through the rest of the GI tract.

As our stomach expands, mechanoreceptors in the stomach sense the expansion and start signalling to our brain. These signals travel via the Vagus nerve and they not only cause the initiation of gastric emptying but also the release of a whole bunch of hormones and regulatory molecules. These include glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), norepinephrine, CCK and, one you’ve may of heard of, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). These signalling molecules not only start to repress hunger but they also act to slow the rate of peristalsis (the rhythmic contractions that push food through our gut). So eating simultaneously triggers movement of food through the gut but also mechanisms that slow that movement so, if working properly, food will make it’s way through out gut at an appropriate speed.

Apart from signalling from the brain our gut is also lined with cells that release signalling molecules in response to nutrients like proteins and fat. These signalling molecules provide feedback as food passes through our gut that helps maintain an appropriate level of hunger, gastric pressure and gut motility. Effectively the nutrient composition of food in the intestines can influence upstream processes like gastric emptying. An example of this is the Ileal brake which is the name given to an inhibitory effect on gut motility and gastric emptying triggered by nutrients in the small intestine. The combined effect of all this signalling is not only the passage of food through our digestive system at an appropriate pressure and rate but also feelings of hunger, satiation and satiety in accordance with the processing status of our last meal.

Although not overwhelming our system with excess food is one consideration, the real aim of eating is to maintain energy levels. So to tie in energy requirements the body has another feedback system which involves two hormones called ghrelin and leptin. A common strategy in the body is to have two molecules that act in opposing ways, we saw this with sleep regulation, and this is what is happening with ghrelin and leptin. Ghrelin is produced in the stomach and it’s levels increase as the stomach empties and it makes us hungrier. Leptin is released by adipose tissue, where fat is stored, in response to it’s fat levels and it represses hunger. The more fat stored by the body the more leptin adipose cells release. In the body the relative levels of ghrelin and leptin can influence how hungry we are and, along with our regulation of blood sugar levels, they are the way the amount of energy we have at hand contributes to how hungry we feel.

This is nothing but a rough sketch of hunger regulation in the body. The real story is a lot more complex and probably not completely worked out yet. The microbiome plays an important part in what is called the gut-brain axis and insulin is also important. There is also a lot of cross-talk between feedback loops; ghrelin for example is involved in insulin signalling among other things. Nonetheless this rough sketch helps us to understand why we get hungry but also what happens when things go wrong. Because, given our current obesity crisis, it’s obvious that things can go very wrong.

Ultra-processed foods get a lot of blame for obesity and armed with our model we can see why. I’ve covered the role of high sugar in UPFs and the insulin feedback loop but the structure of ultra-processed foods is also a potential problem. Because our hunger regulation is so intricately tied to the progression of food through our gastrointestinal tract the softness of UPFs, the lack of fibre needed to provide the raw bulk for gut motility, can confuse our feedback mechanisms. Our gastrointestinal tract is designed to process foods so if our food is pre-processed, so to speak, digestion and absorption of molecules will happen more quickly, our stomach will empty sooner and we end up hungry again despite the calories we have just eaten. If we eat a lot of UPFs, and in some western societies they make up 50% of the average diet, you can see how we can easily start overeating.

But people ate too much before UPFs though so we can’t blame everything on food companies. You can have a low fibre, high sugar and high fat diet without going anywhere near a UPF. This needs another post but speaking in general terms our bodies are tuned to scarcity, that is we evolved under conditions where highly calorific foods such as fats and sugars were relatively scarce. So when we encounter foods that are high in fats and sugars our body tends to make us very happy if we eat them, possible via dopamine secretion. So we ignore our bodies signals of satiety and keep eating because the pleasure of eating outweighs the discomfort.

In western countries, at least, our wealth means we are constantly surrounded by foods rich in fats and sugars, UPFs and non-UPFs, which can make avoiding this hedonistic eating a bit of a challenge. Our brain really can be quite capricious; demanding we stop eating while compelling us to eat just one more chip.

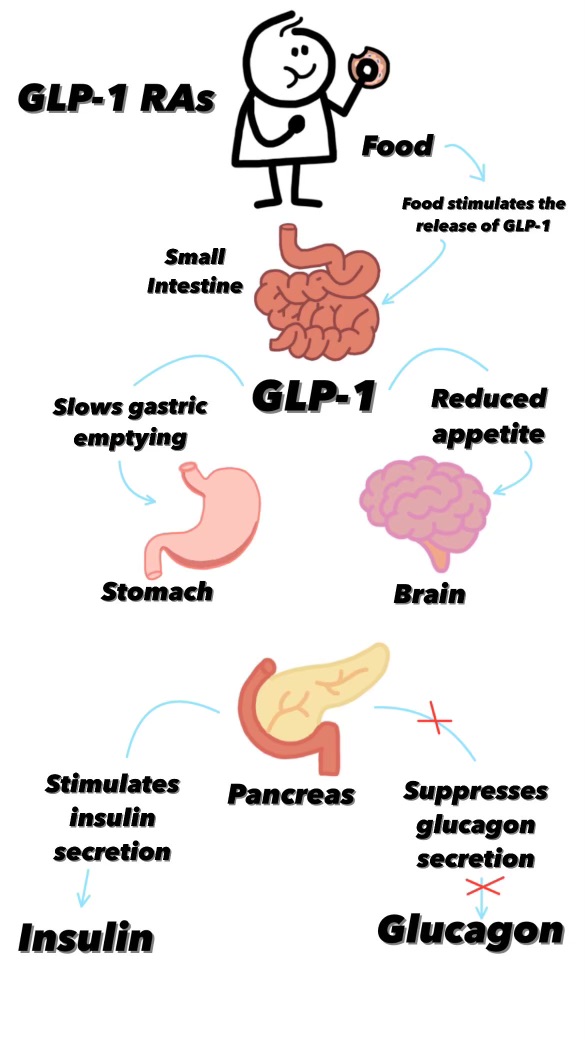

The elaborate signalling that occurs to maintain our energy levels and hunger also provides ample opportunity for medical science to intervene when things have gone wrong. The most famous intervention at the moment are the drugs known as GLP-1 receptor agonists, like Ozempic, Trulicity, Byetta and others1. All of these molecules mimic the natural molecule GLP-1 and are agonists of the GLP-1 receptor. If you remember from the coffee and chilli posts, molecules that bind to protein receptors can be agonists or antagonists; agonists stimulate a response from the receptor protein and antagonists prevent a response. All the GLP-1 medications are activating the GLP-1 receptor, that is they are producing a more pronounced GLP-1 effect than the body would be experiencing on it’s own.

As we saw above GLP-1 is released by the brain after signalling by the Vagus nerve shortly after we start eating and it not only contributes to the feeling of satiation but it also slows the rate of gastric emptying2. That is GLP-1 is one of the signalling molecules involved in the movement of food through our gut, specifically it prolongs the amount of time that food will stay in the stomach and so also prolongs the time before we get hungry again after eating.

But, because this is biology, GLP-1, is involved in other feedback loops. It also influences blood sugar levels by increasing insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells (but only when blood glucose levels are high preventing hypoglycemia) and repressing glucagon secretion. We know that both of these effects also reduce hunger. In fact the influence of GLP-1 on blood sugar levels is why the drug was developed as a treatment for diabetes in the first place. It’s a fortuitous side-effect for dieters, and pharmaceutical companies, that GLP-1 can also be used as a weight loss drug.

The way our body regulates our food consumption and state of hunger is enormously complicated and I’ve only scratched the surface of this topic. In our modern societies we are often trapped between our compulsion to eat and the easy availability of foods that maybe aren’t that great for us when consumed in abundance. Whether understanding why we get hungry is any use in this daily struggle it’s hard to say, but I do like to think that we are not slaves to our chemistry and we are able to exert a level of control, or will, above our homeostatic processes. Whether I’m right about that is probably one for the philosophers.

Leave a reply to Teresa 何 Robeson Cancel reply