Humans have always displayed enormous ingenuity when it comes to short-changing their fellow man. Modern tech companies, with their opaque terms of service and relentless data farming, are a great recent example of this but to capture the eternal nature of man’s duplicity we need look no further than our daily repast. Since antiquity we have complained, legislated and agonised about food fraud and we were probably right to do so. Foods like herbs, spices, bread, beer, olive oil, milk and flour have always been substituted, watered down or adulterated by unscrupulous operators. And more than just getting some substandard produce there can often be much more serious ramifications. Sometimes our health can be on the line1.

Because no one likes being ripped off or poisoned it is not hard to find examples of a historic occupation with food fraud. And punishments tended to be harsh. One of the first legal texts, the Code of Hammurabi from around 1754 BCE, stipulated drowning as the punishment for tavern keepers who charged more for beer than the equal gross weight in grain (though it seems it was only aimed at woman tavern keepers). In China during the Tang dynasty (618CE to 907 CE) killing a customer with dodgy meat would soon see you following them to the after-life. Bakers, because of the importance of bread to everyday life, were constantly viewed with suspicion. In medieval England, for example, a 13th century law called the Assize of Bread and Ale included fines, the pillory, various forms of public shaming and the forced closure of business for offences related to the supply of bread and ale2.

The reason that people commit food fraud is to make some cash so it stands to reason that the more expensive the food the more opportunity for profit. This is where saffron, the worlds most expensive spice, enters the picture. We’ve been using saffron for something like 3000 years and it has probably been the target of fraud for just as long. In ancient Rome Pliny the Elder called saffron “the most adulterated of foods” and in the middle ages Nuremberg, a major saffron centre, had saffron inspectors authorised to burn or bury alive saffron adulterers. Such severe penalties reflecting the financial incentive that saffron fraud offered. In medieval times saffron was probably more expensive than of gold and even today it can cost between $5 and $15 USD per gram, meaning saffron fraud is still financially attractive and still a problem.

Saffron is the dried stigmas from a small flower from a plant called Crocus sativus. Many flowering plants, technically called angiosperms, are hermaphrodites. That is the flower has both male and female parts. The stigma, despite it’s somewhat phallic appearance in C. sativus, is actually part of the female system. Stigmas are sticky and they trap pollen from the air or pollinators like bees. Once on the stigma the pollen grows a long tube down through the style to the ovary where, if all goes well, it reaches the ovule where fertilisation takes place. In many plants the stigmas are smaller protuberances that sit atop the style but in C. sativus they are somewhat longer and, combined with the style, form long threads. It’s easy to tell the stigma and the style apart though because the stigmas are red and the styles yellow3.

Saffron is expensive because to produce it you need to grow a lot of C. sativus, harvest the flowers and then painstakingly pluck the threads from the flowers by hand. There are three threads per flower, and that’s all that should be in saffron, no petals, no stamens just the threads. Ideally, for the best quality saffron, you only want the stigmas, meaning that apart from plucking the thread the red stigma needs to be separated from the yellow style before they are dried. You need a lot of flowers, some 150,000 crocus flowers per kilo of saffron, and a lot of time to carefully — it can be a tricky exercise — pluck the threads from the flowers. Saffron was, and still is, expensive because this process is incredibly time consuming and has resisted all attempts at modernisation. Producing saffron is probably one of the few things we do today the same way we did it 3000 years ago.

Adding to the complexity is the need to act quickly once the flowers start blooming. They begin in the morning and will quickly wilt in the harsh sun so they need to be picked, plucked and quickly dried before being sealed in airtight containers. Growing saffron can also be tricky. Like any crop they have their preferred conditions, hot and moist conditions can harm the crop and spring rain and dry hot summers are optimal. So any bad weather can result in reduced yields as can various pathogens such as nematodes or leaf rusts (a type of fungal disease). In short growing and harvesting saffron is a painstaking, risky venture resulting in a correspondingly high price for the finished product.

Historically people were willing to pay such a premium for saffron not only for it’s uses in food but also because it was an important dye and perfume4. Today we pay for saffron mostly because of the colour and flavour it can bring to our food. The distinctive golden colour is a result of a class of pigment molecules known as carotenoids of which there are several in saffron. Carotenoids are very common in the plant world and they are the pigments that give fruits and vegetables a bright red or yellow colour. The first carotenoid was discovered in carrots, hence the name, but since then over 750 of them have been identified in plants, algae and photosynthetic bacteria. Carotenoids are what make tomatos red, carrots orange and corn yellow; they are also responsible for the warm colours of an autumn forest.

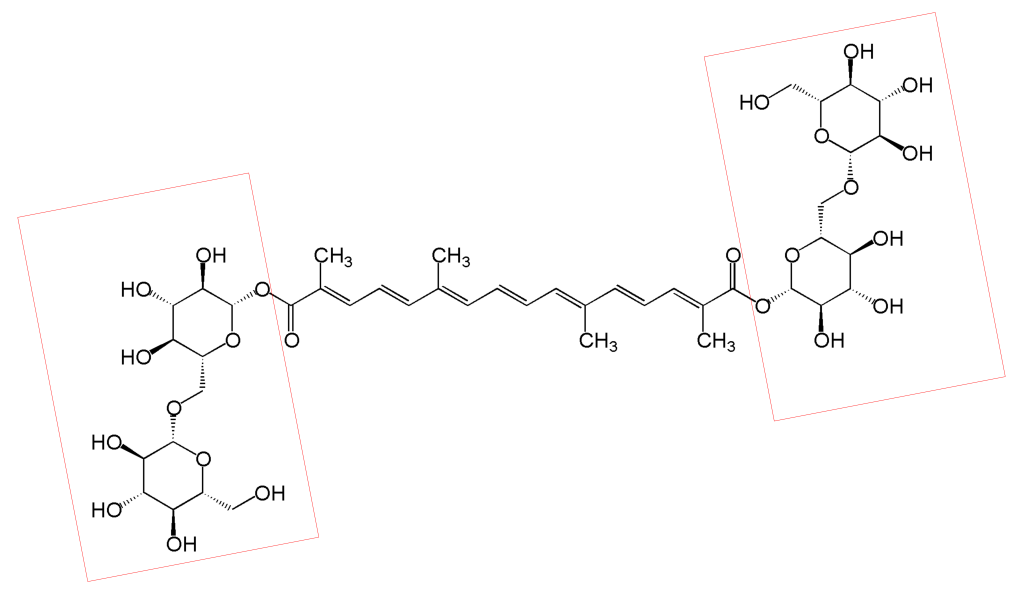

The most abundant carotenoid in saffron is called crocin. Unlike most carotenoids crocin is water soluble thanks to sugar molecules attached to either end of the molecule. This is why saffron is so good at colouring rice and other water-based foods. As the cells of the saffron break down in the heat the crocin dissolves in water and diffuses through the dish. Carotenoids are also antioxidants which might explain some of saffron’s putative health benefits and definitely explains it’s sensitivity to sunlight and oxygen. You want to keep saffron in a sealed container and in the dark because, as we discovered in the redox post, antioxidants can react with oxygen, changing their structure and destroying the flavour and colour of the saffron.

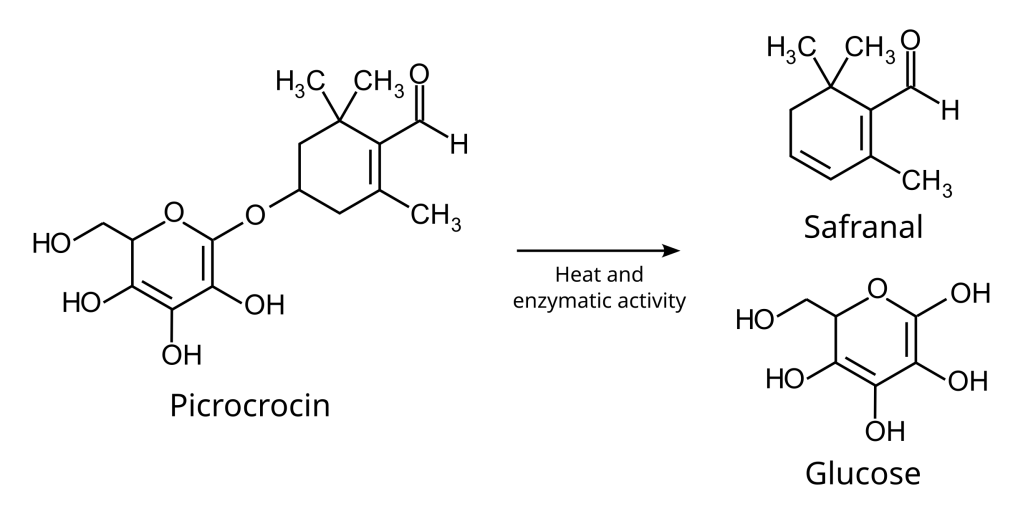

Roughly 160 volatile compounds contribute to saffron’s bitter, slightly metallic hay-like flavour. But one of the most important is a terpene known as picrocrocin. Terpenes are yet another class of plant molecule and they are responsible for many of the odours you find in the plant world, particularly in conifers but they are also behind the distinctive smell of cannabis, familiar to many from their college days. Picrocrocin is bitter but when the saffron is dried heat and enzymatic activity convert some of the picrocrocin to another terpene, called safranal, as well as a glucose molecule. Safranal is not as bitter as picrocrocin so drying is necessary step to reduce bitterness and achieve the characteristic flavour of saffron. One last molecule, memorably named 2-hydroxy-4,4,6-trimethyl-2,5-cyclohexadien-1-one, may be responsible for the dried-hay odour and flavour of saffron.

As I pointed out above the high price of saffron has always made it an attractive target for fraudulent practices and there are a truly impressive number of ways that saffron has been adulterated. Saffron threads can be bulked up using counterfeit fibres made from beet, pomegranate fibres or even red silk fibres. Threads can be mixed with other thread like structures from the crocus flower called anthers. These yellow thread-like structures are part of the male reproduction system of the flower but are tasteless and so worthless. The saffron threads can be made heavier by soaking them with a viscous liquid like honey, vegetable oil or glycerol. Structures from different flowers, such as safflower or marigolds, that look like saffron threads but are tasteless can be mixed with real saffron. Another common method is to impregnate saffron threads with a yellow paste made of barium sulphate and honey and in the past saffron has just been straight up mixed with borates, chlorides, carbonate, sulphate and other salts of sodium and potassium to bulk it up.

Powdered saffron is even easier to adulterate. Turmeric and paprika are common substitutes for real saffron often including colourants that approximate the colour of real saffron. Labelling is another practise bordering on fraud, turmeric has been labelled as ‘Indian’, ‘Mexican’ or ‘American’ saffron, the only real similarity being the price charged for the mislabelled saffron. In short human ingenuity has been utilised to it’s fullest extent in the shabbier parts of the saffron trade (there’s a good paper on the topic here).

Matching the ingenuity of the fraudsters a lot of effort has been put into developing methods for determining the quality of saffron. The easiest way is to throw some of it into water and look to see if you actually have distinctive saffron threads. Because crocin is water soluble you should also see yellow colouring spreading through the water and smell the aroma of saffron. If you dry this extract and draw a rod dipped in sulphuric acid across the surface you should see a blue colour that immediately turns purple and then reddish brown (you can see pictures of this in this paper5). These colour changes are the result of the sulphuric acid reacting with carotenoids, like crocin, that are characteristic of real saffron.

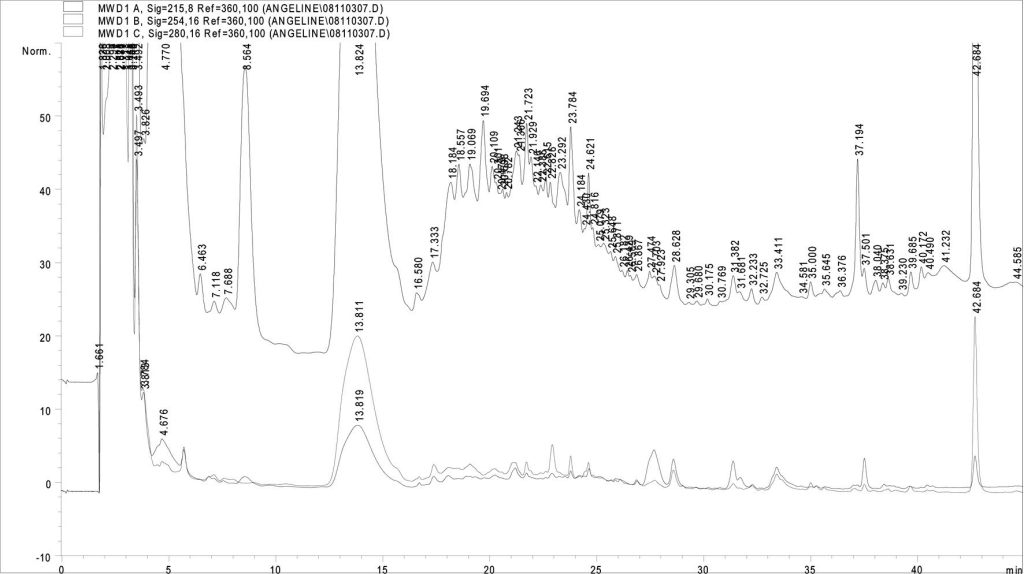

We can also use what we know of the chemical makeup of saffron to design some more quantitative tests. Crocin, picrocrocin and safranal, the molecules so essential for our appreciation of saffron, in conjunction with other molecules provide a chemical ‘signature’ for determining whether your expensive saffron is the real deal. To detect this signature chemists can use a technique called chromatography that separates molecules over time based on some characteristic; size, hydrophobicity and charge being some examples. Using chromatography we can not only identify molecules we expect to be in saffron but also those we don’t, i.e. potential adulterants.

Chromatography can be a bit slow so other strategies have looked to things like infrared spectroscopy and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance to look for a chemical signature of unadulterated saffron in one quick ‘snapshot’. The advantage of these methods is that they are a lot quicker than running everything through a chromatography step. Interestingly, an ‘electronic nose’ has also been developed for analysing saffron. Pure saffron has a distinctive aroma and specific aroma constituents causing electric fluctuations in a sensor set can be analysed using machine learning to detect good or bad saffron (there is a good paper on all this topics here).

Saffron is such a fascinating ingredient a true mixture of the old and the new. Produced using ancient methods but using cutting-edge technologies to detect the oldest of nefarious behaviours. It is a testament to our determination to pursue the most difficult of ingredients while providing a warning of our propensity for taking short-cuts and cheating our fellow man. A spice that not only flavours and colours our food but also teaches us a lesson about ourselves, no wonder it’s so expensive.

Footnotes

- One of the most famous incidents is from 1858 and is known as the ‘Bradford Sweets Poisoning’ saw 20 people die and hundreds get sick after lollies known as Humbugs were extended with arsenic trioxide powder instead of the intended gypsum. There are dozens, even hundreds, of examples of adulterated foods causing sickness and deaths. ↩︎

- This might have led to the term “Baker’s dozen”. In a period before electronic scales bakers would include an extra thirteenth loaf in a dozen to avoid coming up underweight. Or so the story goes. ↩︎

- Ironically cultivated C. sativus cannot reproduce sexually, like bananas, they are triploid and rely on humans to manage their reproduction by replanting bulb like structures called corms. ↩︎

- Wikipedia claims that Nero had the streets strewn with saffron on his entry to Rome. This is truly mind-boggling as I can’t imagine how many flowers would need to be processed to strew the streets of a major ancient capital with saffron. Sure enough, after some more research, there doesn’t appear to be a single historical record of this actually happening. ↩︎

- I agonised a bit about including this paper as the journal it’s published in has some attributes of a predatory journal but the work itself seems good so I went with it in the end. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Mark Cancel reply