Fear is a great motivator and, being in the business of motivation, advertising has always been very quick to take advantage of human uncertainty to build demand. An example of this is the famous “The other white meat” campaign for pork that ran in the States in 1987 and was copied here in Australia during the nineties. The pork industry, alarmed by the success of chicken in positioning itself as a healthy alternative to red meat, tried to piggyback on chickens growing popularity by claiming a similar healthy pale status. It was genius, in a way, back then people cooked pork to well done and when cooked that way it was white, ergo it was white meat, any fool could see that. The campaign worked great for pork, sales went up and everyone was happy. Except, of course, curmudgeonly scientists with too much time on their hands. Because, pork is not a white meat, it is most definitely a red meat.

I am being a little disingeneous here, but only a little bit. Originally the fear factor was fat, people wanted lean meat and pork was definitely becoming leaner back then. But now attention has shifted to haem as a potential downside of red meat and it is not fat that defines whether a meat is red or white, it is simply how much of haem-containing protein called myoglobin is in the meat. Myoglobin is red and so a red meat contains myoglobin and a white meat does not. Most meat that we eat is skeletal muscle so the levels of myoglobin in our meat all comes down to the anatomy of these muscles. More specifically it comes down to how organisms have evolved muscles that are adapted to their way of life and what that means for the amount of myoglobin in our food.

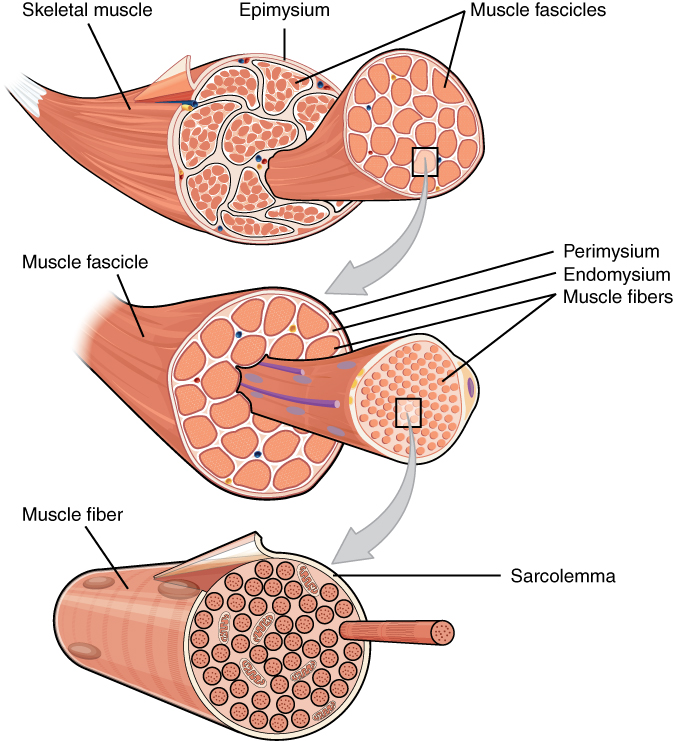

I’ve covered muscle anatomy in my posts on steak and stewing but it’s time to flesh out that model a bit and add some further complexity to understand why some meat is red and some is white. The basic picture of a muscle we have so far is that muscles are bundles of muscles fibres. We also know that muscle fibres are long cells that contain the protein machinery necessary for contractile force. What we need to consider now is how much these muscle fibres can differ from one another. You may of already heard of fast and slow twitch muscles and this is really all I’m talking about. Muscle fibres can be grouped into slow twitch (Type I) fibres or one of two fast twitch sub types (Type IIA and Type IIX) and every muscle has varying proportions of each of these muscle fibre types.

The difference between slow twitch and fast twitch fibres, as their names suggest, is the speed at which they can contract. Fast twitch fibres are larger and have more contractile ‘machinery’ (myosin and actin) but the major reason for difference in speed is how the different fibres get the energy for contraction. We know from my post on fermentation that adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is the energy currency of the cell. During biochemical reactions in the cell ATP gets broken down to ADP (adenosine diphosphate) to provide the energy for the reactions. ADP is then recycled back to ATP using the energy from organic molecules like glucose. We also know that recycling ADP back to ATP, or respiration, can occur in the presence of oxygen (aerobically) or in the absence of oxygen (anaerobically). Anaerobic respiration being what we call fermentation.

The major difference between fast and slow twitch muscle fibres is how they regenerate ATP. Slow twitch muscle fibres are well supplied with blood, so they have plenty of oxygen, and they use aerobic respiration to recycle ADP. Using the Krebs cycle and the electron transport chain in the mitochondria to efficiently produce lots of ATP. The problem is that this is a relatively slow process. Think of a steam engine burning coal and slowly building up speed as it pulls out of the station (it’s not a great analogy but it will do for now). Slow twitch fibres are slow and steady, great for endurance but they can’t support fast explosive movement because in this scenario they quickly exhaust their supply of ATP and can’t replace it quickly enough.

This is where fast twitch fibres come in. Fast twitch fibres can use local stores of glycogen to respire anaerobically which is a much faster way of generating ATP. The problem is that it is less efficient, you get less ATP, and the different chemistry also produces things like lactic acid that needs to be cleared from the cells. But combined with their larger size, more contractile machinery and their ability to rapidly generate force fast twitch fibres are good for short explosive movement, like when a lion jumps out at you or you’re running for the last train that will get you to work on time. Essentially fast twitch fibres support explosive and rapid movement until their store of glycogen runs out. This is why you can sprint for 50-100 meters, before you run out of muscle glycogen and fatigue sets in, but you can jog for kilometers using slow twitch fibres that are supplied with oxygen, glycogen and fatty acids from the blood stream.

The different ways that fast and slow twitch fibres respire means they have different cellular characteristics. Slow twitch fibres are packed with mitochondria, for ATP regeneration, they are well supplied with blood, because they need the oxygen, and they are also rich in myoglobin which is able to ‘store’ oxygen for when it’s needed. Fast twitch fibres don’t need any of this machinery, they have fewer mitochondria, much less blood supply and, the reason I’ve been going on about muscles fibres, much less myoglobin. Meat that is red will have a higher percentage of slow twitch fibres, more myoglobin, and whiter meats will have more fast twitch, less myoglobin.

Myoglobin, like it’s cousin haemoglobin that transports oxygen around the circulatory system, is a protein that is contains a small molecule called haem (which we met in the bacon post). Haem is a small iron-containing molecule that associates with myoglobin and provides the ability for myoglobin to bind oxygen, specifically O2. As I said above, myoglobin is where meat gets it’s colour from. When the myoglobin is oxygenated it is bright red but when no oxygen is bound it is a darker, purplish red1.

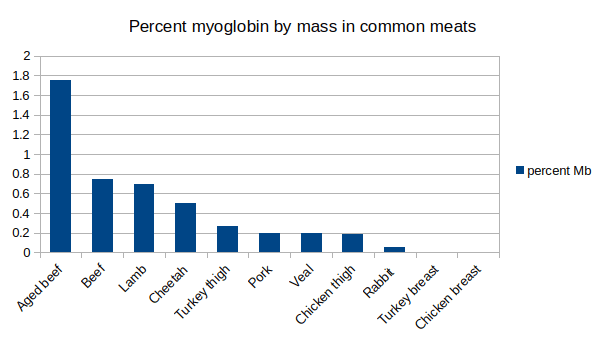

Now we know what makes a meat red or white we can pretty much dispose of the whole red meat versus white meat distinction. What we are really talking about is the amount of myoglobin in a particular meat; an actual measurable parameter. And if we look at myoglobin levels in our common meats we see pretty much what we expect to see. Aged beef has the highest myoglobin by percent of mass in skeletal muscle (1.5-2.0\% ), followed by normal beef (0.4-1.0%), lamb (0.2-1.3%), pork (0.10-0.30%) and veal (0.10-0.30%). On the other hand the classic white meat, chicken breast, has much, much lower myoglobin levels containing only 0.005% myoglobin by percentage of mass.

We can see now why pork is considered a red meat. Although it has way less myoglobin than beef and lamb it also has way more myoglobin than chicken breast. Really no meat we regularly eat comes close to chicken breast (or turkey breast which has 0.008% myoglobin) in terms of myoglobin content (or lack thereof). This is why mammalian meat is generally designated as red meat, mammals we eat just seem to have more myoglobin in their muscles (with the exception of rabbits). Given that we eat herbivores this makes sense. We don’t really think of cows or sheep as being particularly explosive movers so animals with more slow twitch muscles fibres are likely to have more myoglobin.

If most of our common meat is red meat, what is a white meat? Turkeys and chickens don’t fly, they kind of flap quickly to escape or find a perch so they don’t need slow twitch endurance fibres in their pectoral muscles. For this reason chicken and turkey breasts are almost 100% fast twitch fibres and very low in myoglobin. Because they can’t fly they do a lot of walking and this is why leg muscles from poultry are dark meat and have more slow twitch fibres and myoglobin. Fish don’t have to support any weight, they are buoyant and swimming around in water, so they tend to have low percentage of slow twitch fibres (although they do have them and they are the darker parts of the fish flesh). Frogs and rabbits are both ‘hopping’ organisms and both have very low amounts of slow twitch fibres in the muscles used for hopping. So frog’s legs are considered white meat and rabbit is often thought of in the same way.

You may have noticed that there is one meat that we don’t commonly eat in the above graph, cheetah. For no other reason than idle curiosity I wondered if we could improve our diet by eating cheetah. They’re fast so surely they have lost of fast twitch fibres, maybe they are a white meat? You can see from the graph above that that is not the case. They have more myoglobin than pork or veal (the paper is here). It is true that they have about 81% fast twitch fibres in their locomotor muscles but clearly even this proportion doesn’t make for a white meat. I’m also not sure how we could farm an animal that wants to eat us as much as we wanted to eat it, so that idea is a bust.

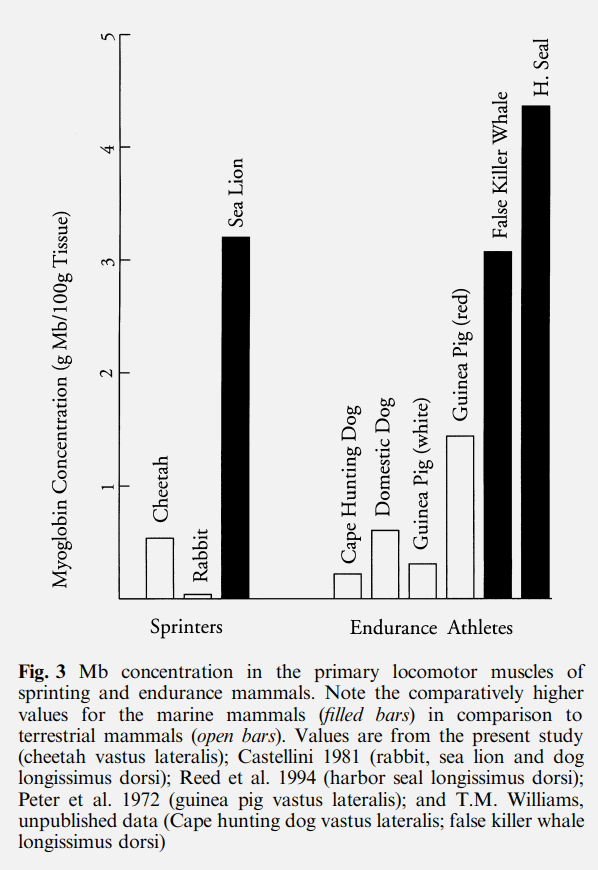

In fact, in a graph (shown above) from the same paper you can see that myoglobin levels are all over the place for land mammals. The real difference seems to be between land animals and sea mammals. Sea mammals appear to have a preference for lots of myoglobin in their muscles. This makes sense if you consider that storing large amounts of oxygen in muscles would be pretty advantageous when underwater, you wouldn’t need to come back up that often. It’s been calculated in humans, for comparison, that there is about 7-10 seconds worth of metabolic activity stored in skeletal muscle oxygen stores whereas a sea lion has 47% of total oxygen stored in myoglobin. So the evolutionary driver for myoglobin in mammals may actually be an aquatic lifestyle.

An interesting question that this raises is do land mammals need myoglobin at all? Mice genetically engineered to have no myoglobin seemed to survive quite well (see here). And, though this is just speculation, if it turns out the haem is the problem molecule in red meat (which may well be the case as we discovered in my bacon post) could we engineer cows without myoglobin? I’m not sure if we really want to go down that path but it’s a curious idea.

OK I’m really digressing so lets get back to pork. Pork isn’t the other white meat, it’s a red meat like all other mammals (with the possible exception of rabbits). But you may still not be convinced. When you cook pork it is white, how can it be a red meat? Well there are a couple of things going on. Firstly, the amount of myoglobin in the meat increases with age and pigs are generally slaughtered at an earlier age than beef. Pigs are slaughtered at 5-7 months while beef are slaughtered at 12-22 months. The pigs probably being a victim of their success at eating and putting on weight. Veal, for example, is early slaughtered beef and it’s myoglobin levels are pretty close to pork’s.

The second factor is that as myoglobin heats it denatures and loses it’s ability to bind oxygen and the meat turns opaque. This happens in beef just as much as pork but we tend to eat beef rarer than pork. A well done steak is also pale on the inside but the beef also has much more myoglobin so you get a pale brown. A rare steak on the other hand is red on the inside because it has more intact myoglobin and no oxygen so it’s nice and red. Pork cooked to the same rareness would be the same except it will be pink because it has a smaller amount of myoglobin.

Ultimately all this ‘is it a red meat or a white meat?’ is beside the point. Leaving fat content aside, current thought is that high levels of haem are thought to be carcinogenic because of it’s role in the production of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds. The other source of carcinogens in our meat are the heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that can form when meat is cooked at high temperatures (such as grilling or BBQing) but this happens regardless of the meat’s putative colour. So we should really forget about the red/white meat thing and just think about haem. In this scenario pork has less haem than beef but still a whole lot more than chicken. So if you are worried about red meat pork might be better than beef but it’s not as good as chicken breast, and eating cheetahs, if you can catch them, wont help either.

Leave a comment