I’ve been reliably informed by influencers, billionaires, failed comedians, politicians, Twitter pundits and assorted spite-filled meat-puppets looking to build an audience that diversity is a bad thing. Now I’m not one to disagree with the new intelligentsia but as a scientist, a member of the old intelligentsia I guess, I can’t help but feel, deep down inside, a sense of disquiet. Because really a lot of this talk, while it is not usually an outright declaration of support for eugenics, comes pretty close. There always seems to be a subtext underlying the conversation about diversity; certain presidents talk about ‘bad’ and ‘good’ genes, Silicon Valley oligarchs fund foundations promoting pseudo-scientific theories of social Darwinism and some members of the on-line right community barely even disguise their belief in the need to maintain racial purity.

But, you may ask, what has this to do with food science? I’m sick of politics get to the food, you may think. Well my hook today is that the humble banana has an important lesson to teach about genetic diversity and it seems to me that many participants in this discourse don’t possess a clear understanding of some simple genetic fundamentals. I think they need to listen to the banana. See nature is pretty sure that diversity is a good thing. In biological systems, at least, a sure path to extinction is a lack of diversity in your gene pool. Genetic diversity provides a pool of potential solutions to unknown problems. When pathogens evolve, food systems are destroyed or any other environmental stress comes along and changes the game, genetic diversity can save you. And the banana understands this better than most.

So, in this post I want to do what many pundits don’t bother to do; the boring bit, we need to learn some science. And before we get to the banana lets look at some basic genetics and start with an organism we’re all familiar with, humans. Most of us know that humans have two copies of a complete genetic code. We have 23 pairs of chromosomes one of which we received from our mother and the other from our father. Encoded at specific locations on these chromosomes are genes. Every one has heard about genes and we probably all know that the specific genes at chromosomal locations can differ from person to person. These different versions of the same gene are called alleles. Because we get a set of chromosomes from each parent we inherit two alleles for a gene, one from mum and one from dad. If they are the same allele then we have two copies of one allele (and we are homozygous for that gene) otherwise we’ll have two different alleles (and we are heterozygous for that gene).

Given that we can have two different versions of a specific gene this is where things can start to get complicated. Both alleles can be expressed or only one and this affects what is known as our phenotype, the physical manifestation of our genes. One of the simplest examples of this is eye colour. To have blue eyes you need two blue eye alleles because one brown eyed allele and one blue eye allele will give you brown eyes, as will having two brown eye alleles1. The brown eye allele is called the dominant allele, and the blue recessive, because if you have one of each the brown eye allele will give you brown eyes and ‘dominate’ the blue eye allele. So in this situation your phenotype would be brown eyed because your genotype is one blue eye allele and one brown eye allele. I’ve calculated some simple Punnett squares below to show how genotype and phenotypes can be calculated.

This is all we really need to know to understand genetic diversity. Genetic diversity is basically the number of alleles for a gene in a population. If there is a population with only brown eye alleles then the genetic diversity is low, because everyone has the same alleles for the eye colour gene and everyone has brown eyes. If there are blue and brown eyed alleles in the population then genetic diversity is higher and a small percentage of the population will have blue eyes and a proportion of the population will have brown eyes but will still carry a blue eye allele (they have one brown and one blue eye allele).

We can now also get some idea of the dangers of low genetic diversity. Lets say something happens that makes having the blue eye allele protective for some disease, a disease that kills or otherwise prevents people without a blue eye allele from reproducing. A population that only has brown eye alleles has a big problem; the writing is on the wall because the only allele in that population is for the brown eye allele. The population with blue and brown alleles is likely to survive, not only does it have individuals with blue eyes who wont be affected at all, but it also has a proportion of brown eyed individuals with a blue eye allele, that may also offer some protection from the disease. In this situation the population with the greater genetic diversity, the population with brown and blue eye alleles, will survive while the population with only a brown eye allele will not.

This may sound far-fetched but it is a very real and there are multiple examples of common human alleles that protect against disease. Examples include an allele for the CCR5 gene that makes individuals resistant to HIV, APOL1 variants can provide resistance to trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) and FUT2 mutations can provide resistance to norovirus infection (see here if you want to learn more). Ironically, some of these alleles lead to medical conditions in other contexts and if we were an enthusiastic eugenicist we might have thrown these alleles out of our population in a misguided attempt to ‘improve’ our genetic stock.

The classic example of this are individuals who are heterozygous for sickle cell anaemia. Having one copy of the mutation that causes sickle cell anaemia makes you more resistant to malaria than someone with no mutated alleles. But having two mutated alleles gives you sickle cell anaemia and makes you more susceptible to malaria. Because of this a disease causing allele, the one that causes sickle cell anaemia, is extremely common in African populations because having one copy of this allele protects against malaria, another deadly disease (you can read more about this story here). I’ve calculated a Punnett square for sickle cell anaemia and malaria below.

So what do bananas have to do with any of this? Well everything that I said so far goes for plants as well. The genetic code is pretty much universal (with some edge cases) and so the mechanisms of genetics and evolution hold across all living organisms, on Earth anyway. But with some species of plants, the ones important to humans, we have examples of what selective breeding can do to genetic diversity. Crops like wheat, rice, maize and many others have been subject to human selection for a millennium. Over this time we have selected for specific traits, selecting a restricted number of individuals with the desired phenotype from each generation for propagation into the next.

In most cases selected breeding inevitably leads to a decrease in the genetic diversity of a species or population. Because individuals can only carry two alleles for any gene, if there are 20 alleles for a gene in a population and you select four individuals for propagation at most you can keep eight of the alleles, probably less. The situation can get even worse in plants that are able to reproduce asexually (in plants called vegetative reproduction and we’ve seen this in potatoes). In these species, parts of a plant, such as runners, rhizomes, tubers, and bulbs, can give rise to multiple copies, or clones, of a plant. Breeders can also promote vegetative reproduction artificially using cuttings, grafting or layering. This means that plant breeders can potentially select one individual from an entire population for propagation, effectively reducing genetic diversity to zero for that population (i.e. they are all clones of the one parent).

If you are a farmer this makes sense, you don’t want to take a risk on unknown genetics you want exactly the plants that provided a great yield last year. The problem is the vulnerability that comes with having a highly uniform population. If something changes in the environment, say the climate changes or a pathogen evolves in a novel way, a genetically uniform population can be in serious trouble. As Alanis Morissette might have said: a species can end up having ten thousand spoons when all it needs is a knife. This has become a major issue in our food systems as by some estimates we have lost about 75% of genetic diversity in our crops over the last century (see here), meaning that some of our most important food crops could lack the genetic diversity needed to see off coming environmental challenges.

It can get even worse for some plants. Some cultivated plants have lost the ability to sexually reproduce at all. This means all the individuals within the ‘species’ are clones with zero genetic diversity. Any seedless variety of fruit and vegetable is an example of this, like seedless watermelons or grapes. These varieties are often produced by exploiting plants ability to tolerate more than two sets of chromosomes. Most organisms are just like humans and have two sets of chromosomes and are referred to as diploid. Occasionally, however, an individual can end up with more than two sets, a condition called polyploidy. In humans, in rare cases, someone can be triploid and have three sets of chromosomes but this almost invariably results in severe developmental defects. Plants, on the other hand, are more tolerant of extra sets of chromosomes and polyploidy, or at least evidence of historical polyploidy, is fairly common.

Wheat for example is hexaploid (six sets of chromosomes), potatoes are tetraploid (four sets) and strawberries win the polyploidy competition with a massive eight sets of chromosomes (octaploid). Polyploidy can occur a number of ways but one common way is by hybridisation, where two different species, or varieties, reproduce forming a polyploid offspring. This is probably the reason most of our crops are polyploid, either because we selected naturally occurring polyploid variants with desirable traits or we crossed two different species to achieve an offspring with favourable traits.

Although plants are capable of establishing a stable genome with more than two sets of chromosomes, sometimes polyploidy leads to sterility. Polyploidy, for example, can result in the loss of seeds which is a common way for us to breed seedless varieties of fruit. In the wild this could be a catastrophic turn of events for an individual, condemning them to vegetative reproduction, if able, or extinction if not. But when humans are around the loss of seeds can be a good thing. The inability to produce seeds becomes a survival trait if there are humans around who enjoy the convenience of not having to spit out seeds and are happy to manage the asexual reproduction. The problem, of course, is that the species, or population, has zero genetic diversity.

And this finally brings us to bananas. There are anywhere between 300 and a thousand different varieties of banana and mostly they are sterile seedless triploid crosses of two wild banana species, Musa balbisiana and Musa acuminata2. Although wild bananas can and are eaten, they are smaller and mostly seeds so cultivation efforts have aimed at increasing the size of the fruit and getting rid of the seeds. In a Cavendish banana, for example, all that remains of the seeds are the vestigial black dots that run down the centre of the fruit. Hybridisation and, in most cases polyploidy, are the mechanisms we have used to make a banana that is easier and more enjoyable to eat.

Despite the wealth of banana varieties, most people are mostly familiar with the Cavendish banana. Cavendish bananas make up about 40% of the world wide banana stock and are overwhelmingly the variety we are likely to encounter in a trip to the supermarket. The reasons for this is that the Cavendish banana has a higher yield, more bananas per tree, has a thick skin, which protects it during transportation, and it takes longer to ripen, giving it a longer shelf-life and better ability to be transported. In short it is a banana that is suited to our global logistics networks. But, because it is sterile, it is a clonal population that can only be propagated using vegetative reproduction. And this makes it vulnerable.

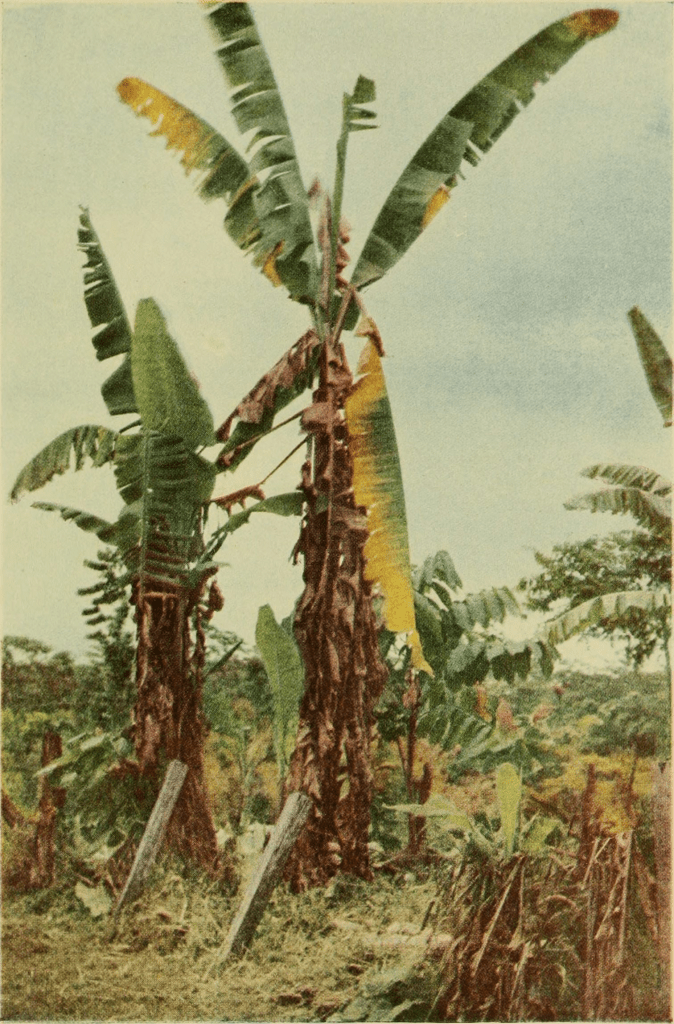

In fact, before the 1960s one banana dominated the world’s supply and it wasn’t the Cavendish, it was a variety known as Gros Michel (or Big Mike). This variety was similar to our Cavendish but had a firmer texture and, according to the experts, had a more intense banana flavour3. But the Gros Michel was a clonal population that relied on vegetative propagation and in the 1950’s it was effectively wiped out by a soil-borne fungus that caused Panama disease. Because the Gros Michel had no genetic diversity it had no ability to resist the disease and there was little that we could do to save it. Luckily, we had the Cavendish variety waiting in the wings. Not only was it similar to the Gros Michel in most ways but, crucially it was immune to Panama disease. So, disaster avoided.

The problem, of course, is that we are back to exactly the point that we were with the Gros Michel. A worldwide banana market dependent on a vulnerable clonal population. It is almost inevitable that we will lose the Cavendish as well. Fungal diseases like Black Sigatoka and Fusarium Wilt Tropical Race 4 threaten and the Cavendish has no resistance to these diseases (you can read more about this here). Unless we manage to pull off some genetic engineering wizardry we are going to have to go back to the drawing board and develop a new variety of resistant banana. If it is another clonal variety then we’ll have to do it all over again in the future because low genetic diversity does not make for a robust, resilient species.

The banana shows us that genetic diversity is essential for the long term survival of any species or population. Indeed, there is a pretty compelling theory that sexual reproduction evolved specifically to maximise genetic diversity. Although I didn’t get a chance to touch on it above, meiosis (a form of cell division that produces gametes, i.e. sperm and eggs) ensures that every gamete receive a mixture of alleles from both the mother and father chromosomes. This ensures a wide range of genetic potential in every generation as parental alleles are mixed up and ultimately combined with someone else’s random assortment of parental alleles. In a way every child is a little genetics experiment.

This blog post is not a comprehensive discussion of the ethics around genetic engineering. It’s more of a plea to understand the basic science before throwing around lazy statements about diversity or indulging in the ‘good’ gene versus ‘bad’ gene narrative. Humans aren’t bananas, and we can’t reproduce asexually (not yet anyway), so we are not likely to ever be as vulnerable as the Cavendish. But low genetic diversity has still occurred many times in human populations, in populations with a high degree of inbreeding for example, and it’s always devastating4. Think of royal dynasties who indulged in consanguineous marriages5 (that is marriages between individuals closely related; second cousin and closer generally). Selective breeding inevitably leads to reductions in genetic diversity and it would be a brave engineer who would be happy designing a human that he or she thinks has all the genetic infrastructure necessary for all possible futures6.

We also don’t have a lot of genetic diversity to spare. Humans already have low genetic diversity when compared to other primates, probably as a result of a genetic bottleneck some 50,000-60,000 years ago. Likely caused by a small population moving out of Africa. Indeed, to this day Africans have greater genetic diversity than other human populations (see here for more on this). So we probably can’t afford to throw out too much of our limited genetic diversity chasing some dream of a ‘better’ human7. Just like bananas we are limited by our biology and to avoid ending up like the Cavendish or Gros Michel, an attractive but ultimately doomed species, we need to value our diversity and make sure we have a deep well of genetic potential to face all the problems that an uncertain future will throw at us.

Footnotes

- It’s actually much more complicated than this but as an example it is a good starting point. ↩︎

- This may be a simplification as recent research suggests other species may have contributed DNA. There may be at least three other ‘mystery’ species that have contributed DNA to modern cultivars. ↩︎

- Apparently the Gros Michel produced more isoamyl acetate than the Cavendish. Isoamyl acetate is a volatile ester that has an aroma characteristic of bananas. It is the flavour of banana essence and those banana lollies we used to get as children. ↩︎

- I’ve mostly talked about genetic diversity in the context of genetic potential in the face of environmental challenges but low genetic diversity also means that you have a greater chance of inheriting two recessive alleles for a serious medical condition. In inbred populations the low diversity means that your parents are more likely to carry the same rare allele for a genetic condition than two strangers from a population with a lot of genetic diversity. ↩︎

- The Spanish Habsburgs, for example, married their cousins partly to maintain a pure royal bloodline (where it was called limpieza de sangre). This didn’t work out too well for them. ↩︎

- I’m also sure that you would not find an genetic engineer capable of such a feat ranting on X (Twitter) about the need to remove inferior genes from the gene pool. ↩︎

- Probably better addressed in another post, but evolution is selection of the fittest in the context of a specific local environment, so any question of a ‘better’ human then becomes better for what? Anyone of northern European extraction living in Queensland knows that being white in that environment is not a great trait unless you like regular skin cancer checks and the need to slather yourself with sun block every five minutes. ↩︎

Leave a comment