About Quick bites

Quick bites are shorter very specific posts that add some extra information that was too much for a regular post but which are worth knowing anyway. They can also highlight some important biological or chemical principle that can be referred to rather than explain the same thing over and over in different posts.

In my recent post on MSG and our taste perception I was going to include a bit about salt and how it works as a flavour enhancer but, as usual, I went on a bit so I couldn’t fit it in. So I wanted to do this short post while it was all fresh in my mind to have a quick look at salt, how it works in our gustatory system and why this makes it so important when we are cooking. We all know that salt, sodium chloride (NaCl), makes your food taste better and chefs, savvy home cooks and processed food companies all use salt to heighten the flavour of their food. Humans use of salt is not just a recent thing, there is evidence of human salt production going as far back as 6000 years ago. You also may have heard that Roman soldiers were paid in salt, which isn’t actually right, they were paid in money but they called it ‘salt money’ because they would use some of it to buy salt. Salt is essential for our good health, sodium is required for the proper functioning of our nervous system and muscles for example. But it is its flavour enhancing properties that has had us passing the salt for the last 6000 years.

When it comes to salt in our food there are quite a few things going on. Firstly, apart from enhancing flavour, salt has a flavour of it’s own so when you add salt you are increasing the perceived saltiness of the food. Most of the flavour of saltiness seems to come from sodium, although chloride may have some role in modulating the strength of the taste. Not a lot is known about how the salt taste happens but at least one ion channel receptor has been identified, the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC). This receptor responds primarily to sodium and lithium, but can also be stimulated to a lesser extent by other ions such as potassium. This has some consequences when looking for sodium free salts. The range of potential molecules that can interact with the ENaC receptor is much smaller than, say, the sweet receptors and low sodium salts basically boil down to replacing some or all of the sodium chloride with potassium chloride.

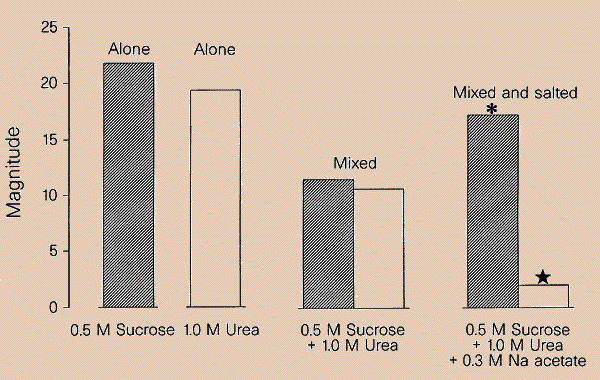

Apart from a taste, one of the major ways salt acts as a flavour enhancer is by masking bitterness. Once again it is sodium that seems to be responsible for this activity. How salt masks bitterness is still a bit of a mystery. In particular it isn’t really known if salt represses bitterness peripherally, that it interrupts the operation of the bitter receptor, or centrally, that the increased saltiness of a dish causes the brain to reduce the perception of bitterness.

On the internet there seems to be a lot of talk about ‘cross-modal perception’, which I guess correlates to a central mechanism. But in the scientific literature one early paper suggests that sodium can bind to the bitter receptor and prevent it’s activation by bitter molecules (see here) and a recent paper also showed that at least some bitter receptors are actually inhibited by the presence of sodium (see here).

For my money the fact that salt masks different types of bitterness at different levels and even fails to mask some bitterness altogether, salt doesn’t seem to mask the bitterness of tetralone for example, makes me think it is a receptor mediated process. The differences in bitter receptors would account for differences in the efficacy of salt to mask the bitterness. But that’s just one opinion, I’m sure those working in the field know a lot more and will sort it out.

Salt’s effect on sweetness is normally explained as a by-product of it’s ability to mask bitterness, food just seems sweeter because salt is repressing the effects of any bitter molecules. But this may not be the whole story. In the MSG post I talked about the sweet receptor being a complex of the TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 proteins, but, and I didn’t go into this, mice without these receptors can still perceive sweetness if salt is also present.

In a recent paper the sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) receptor appeared to make the nerve impulses from TAS1R proteins to occur more frequently when mice were fed salt and glucose than when fed only glucose (the paper is behind a pay wall but there is a good summary here). If this mechanism is also present in humans then salt not only increases sweetness by masking bitterness but it also acts to intensify the sweetness by interacting with SGLT1 and sending a greater number of sweetness signalling nerve impulses to the brain. Sprinkling a little bit of salt on watermelon or other fruits is an old chefs trick and this could explain why it works. It could also explain why salted caramel is so delicious.

Finally, salt is also able to enhance all flavours to some extent and this ability comes down to the ability of salt to lower the activity of water. Water activity is a chemical concept and, in technical terms, it is a measure of the ratio of the vapour pressure of water in a system to that of pure water at the same temperature. A much simpler explanation is that it is the amount of water in a system that is available for chemical reactions or interactions with other molecules. If you compare salty water to pure water you’ll find that the salty water has a lower activity because there is a bunch of water interacting with the Na+ and Cl- ions from the salt that are not available to do other things (which is why the vapor pressure is used to measure it – if the water is bound to something than it is not available for evaporation so the vapour pressure decreases).

Remember that for a molecule to be tasted, that is to interact with a taste receptor, it needs to be dissolved in saliva and enter the papillae where it can interact with a taste receptor on a taste bud. If there is no salt in your food then the water activity in the taste bud will be higher, so there will be more water available to interact with the specific molecule and not the receptor. If there is salt present then the water will be interacting with the salt which means a lower water activity or less water available in the system. Essentially, by adding salt you are increasing the concentration of the food molecule which means more receptors are interacted with and more signals are sent to the brain which increases the perceived flavour of the food.

To circle back to MSG, the reason we buy monosodium glutamate and not just pure glutamic acid is that the sodium, which we’ve seen causes most of the flavour enhancement properties of salt, is also able to enhance the umami flavour. I’ll probably need to come back to MSG at some point, the mechanism of umami flavour is a lot more complicated than just interacting with a single receptor. We’ve seen that the umami receptor is actually constructed from sweet receptors so it is not unreasonable to think that sodium is also able to amplify the umami flavour via some receptor-mediated mechanism similar to what we see in mice with SGLT1 and sweetness perception. Also if you’ve tried straight MSG you’d know that it is not a pleasant experience, and the taste of pure glutamic acid has been described as more sour than umami. Umami taste is clearly much more complex than I have described here and I think it is safe to say that we know very little about how we perceive it, or any of the other tastes for that matter. The good thing is that even if we don’t understand how taste works it still works and I can continue to enjoy salted caramel even if I don’t know how I am enjoying it.

Leave a reply to writinstuff Cancel reply