About Quick bites

Quick bites are shorter very specific posts that add some extra information that was too much for a regular post but which are worth knowing anyway. They can also highlight some important biological or chemical principle that can be referred to rather than explain the same thing over and over in different posts.

In my last post on emulsions I was a pretty loose with my terminology when referring to fats, oils, lipids, cholesterol etc. In this Quick Bite I just want to explain some of the terminology and start getting a bit more precise about what I mean when I say ‘fat’ (or an oil which is just a fat that is liquid at room temperature) or ‘lipid’ or ‘phospholipid’. I also thought a quick primer on what the different types of fat are would be a good idea. There’s a lot of talk in the media about good and bad fats and terms like saturated, mono-unsaturated and poly-unsaturated get thrown around a lot. If you’ve ever wondered what these terms actually mean and you don’t mind some chemistry then this is the blog post for you.

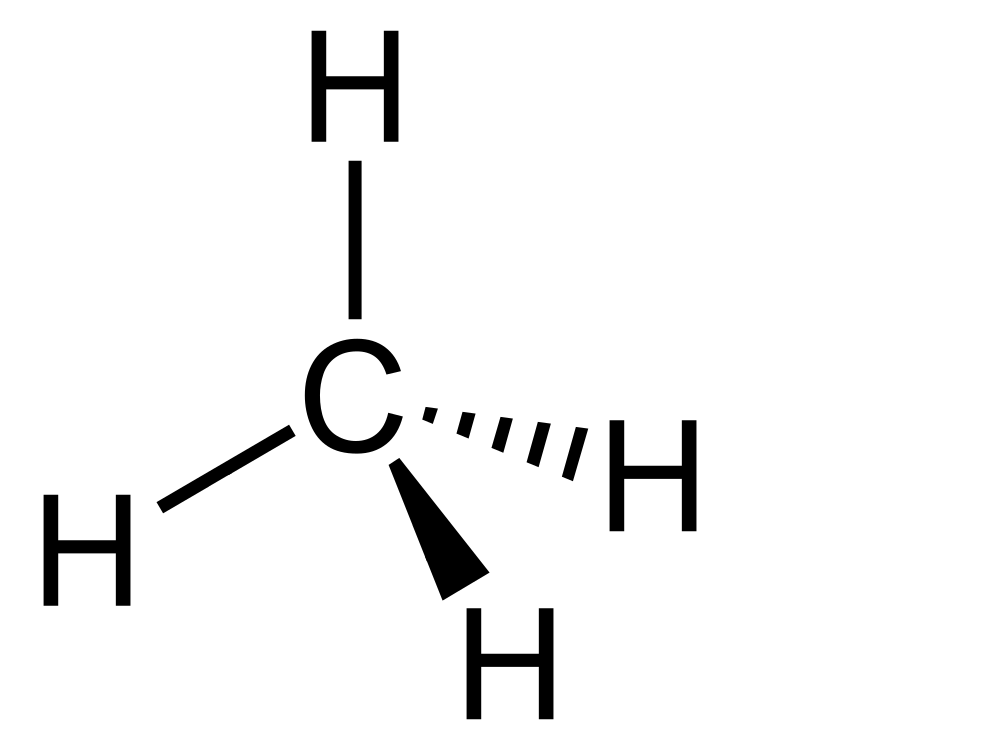

I want to start with the carbon atom. All life on earth is carbon-based and this is because the chemistry of carbon gives it enormous flexibility in forming a wide range of different molecules with different chemical properties. DNA, RNA, proteins, carbohydrates and fats are all large biological molecules with a carbon skeleton that provides the structure to hang a bunch of chemistry off. Key to this versatility is that carbon can form chemical bonds with four other atoms. For example, the simplest carbon based molecule is a single carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen bonds, this molecule is called methane (which you may have heard of as the second most abundant greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide).

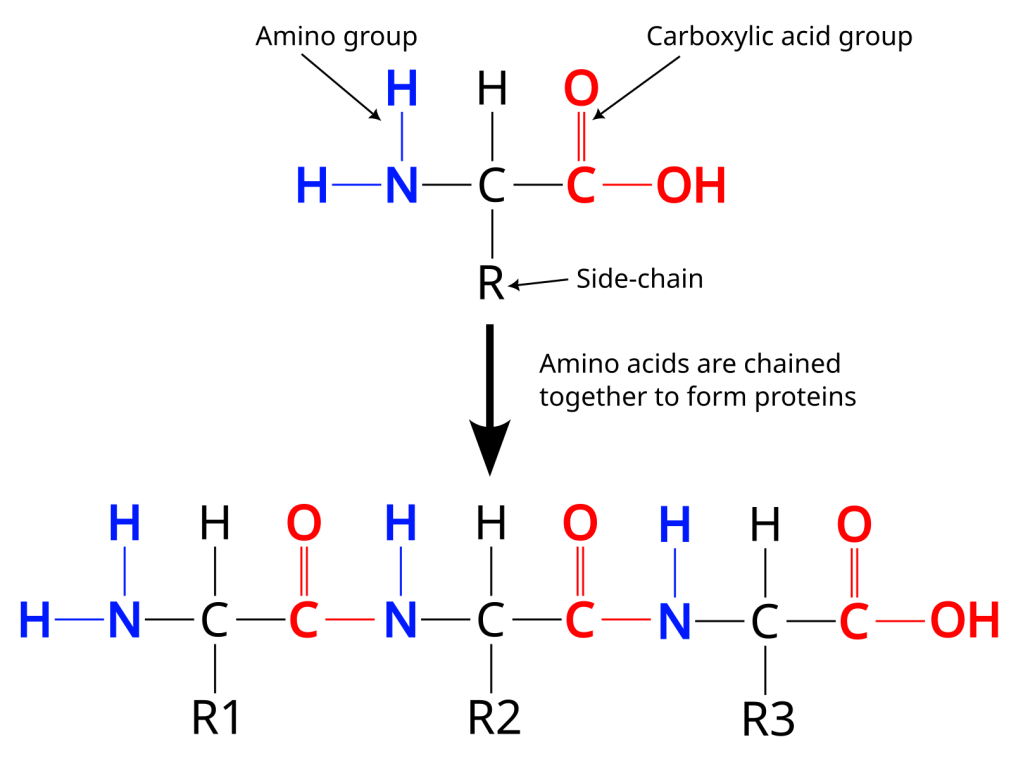

Because of it’s ability to form four chemical bonds with other atoms carbon atoms can form a wide variety of different chemicals. They can form rings, like we saw in sugars, or they can form a backbone for subunits that can be joined together in chains to form long biological molecules. We saw this when we looked at proteins, which are formed of long chains of amino acids, and it is also the case for the individual nucleotides in DNA and RNA. Peptides and nucleotides are both formed from a carbon backbone. Fats also can be looked at as large biological molecules formed around a carbon backbone.

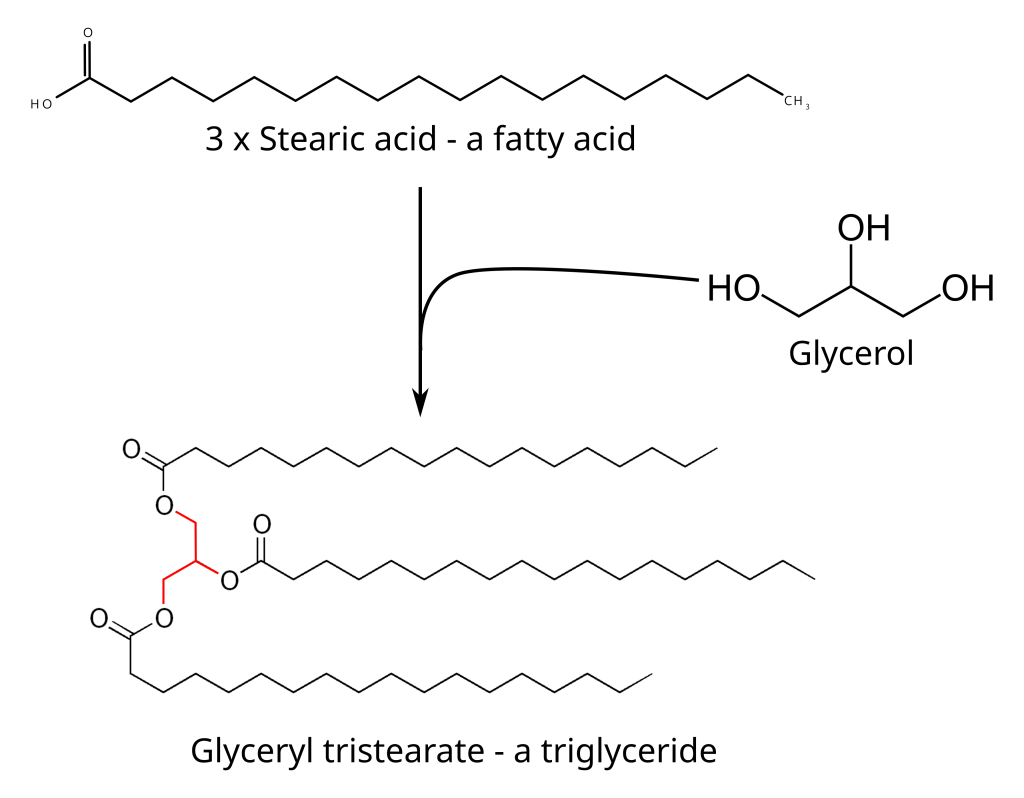

Fats are a subclass of a class of molecules that are called lipids. Lipids include things like fats, waxes, fat-soluble vitamins, glycerides and phospholipids, amongst others. All of these molecules are of vital importance to human biology as fuel for cellular metabolism, energy storage molecules and as structural molecules. For example, every cell in our bodies, and cells from all other living organisms, has a cell wall and this cell wall is made up of phospholipid bilayers. Human body fat is a type of lipid called a triglyceride which is a molecule (technically called an ester but don’t sweat the chemistry too much) composed of a glycerol molecule and three fatty acids. A fatty acid is also a lipid and it contains an acidic head and a long chain of carbon atoms. There are many different types of fatty acids and a triglyceride can have any combination of fatty acids.

Fatty acids can be classified according to several different characteristics but a common way, and the way most of us have heard before, is by whether the long carbon chains contain double bonds or not. Carbon, along with a few other elements (mostly in the second period of the periodic table like oxygen and nitrogen) can form double bonds in which they share four electrons with another atom. When carbon does this can still only form four bonds and the double bond counts as two bonds. So in a specific fatty acid carbon chain you could get no double bonds, one double bond or more than one double bonds. When a triglyceride is formed with three fatty acids, if there are no double bonds in the carbon chains it is a saturated fat (because all the carbons have the maximum four bonds two with hydrogen atoms), if there is one double bond it is called a mono-unsaturated fat and if there are more than one double bonds it is called a poly-unsaturated fat.

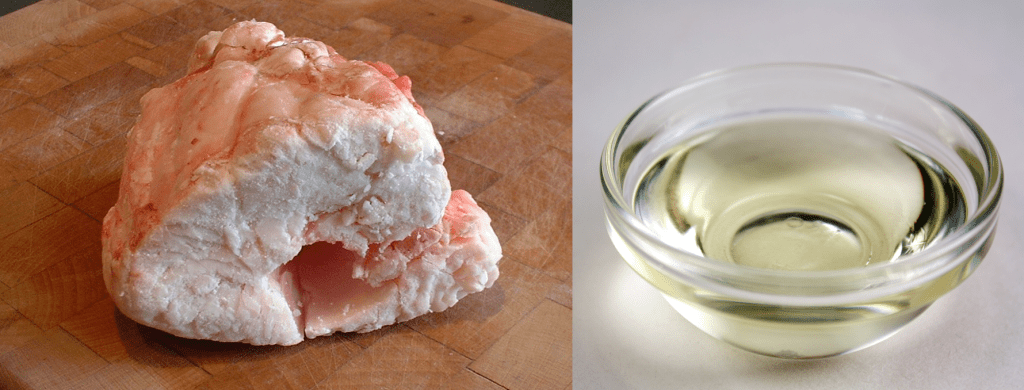

In general animal fats tend to have more saturated fats and plant fats more unsaturated fats. From our own experience we know that animal fat tends to be solid at room temperature, the fat on a steak or in bacon, and plant ‘fats’ come as oils, canola and sunflower oil for example. The reason for this is that when there are no double bonds in the fat molecules they don’t have any kinks and so they can pack together more efficiently. This makes them solid at room temperature. The double bonds in unsaturated fats do cause kinks in the carbon chains meaning they don’t pack together as well and at a given temperature they are more likely to be an oil than a solid.

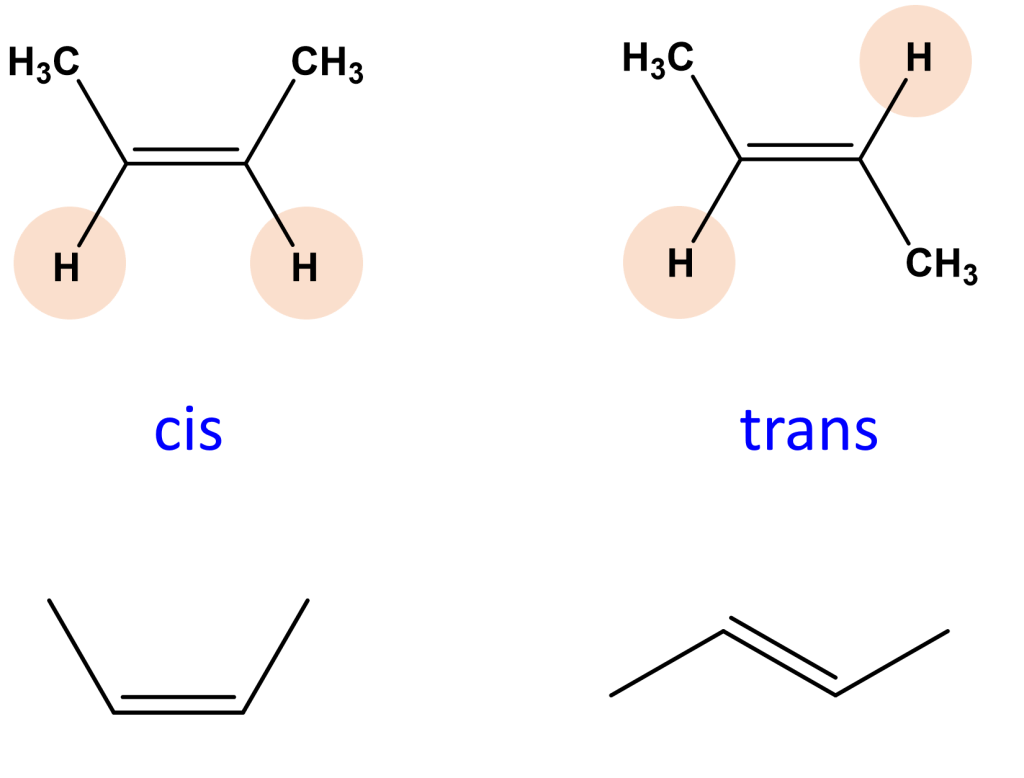

This brings us to trans fats and there is one more bit of chemistry we need to know so we can understand these types of fat. When two carbons are involved in a double bond in a carbon chain they can be in a ‘cis’ or ‘trans’ conformation. One way of thinking about this is that when there is a carbon double bond the two carbons involved will have two bonds with each other, another bond with the previous or subsequent carbon atom in the chain and one bond left for a hydrogen atom. The carbon atoms in the double bond can rotate about the bond which means that the hydrogens attached them can be on the same side of the double bond (cis) or different sides (trans). The figure below shows it better than I can explain it. One of the main consequences of having a cis or trans bond is that you get a much bigger kink in the carbon chain with a cis bond than you do with a trans bond.

Trans fats came about because people wanted to make the vegetable oils solid, like margarine. To achieve this food scientists we’re able to use a chemical reaction called hydrogenation to remove double bonds from the fatty acid chains of vegetable oils. Because the double bonds are what cause the kinks in the fatty acid carbon chains, by removing them you can make plant oils solid at room temperature. But a side-effect of this process is the introduction of some trans bonds into the fatty acid chain (hence the name). This is fine for solidifying the oil, because trans bonds are less kinked, but it turned out not so good for our health because trans-fats, as we’ve slowly discovered, are quite bad for us. This is ironic as one of the benefits of trans fats was meant to be that we could replace saturated animal fats with plant fats (i.e. margarine for butter) and because plant oils are better for us it was assumed that the trans-fats would be better for us too.

I’ll leave the reasons why the various fats are thought to be good, bad and moderately bad for us to another post. Except to say that it has to do with the levels of low-density (LDL) and high-density lipoproteins (HDL). In the Emulsions II post I went through how LDLs and HDLs are micelles that transport hydrophobic fats (and cholesterol) around the body. Consuming different types of fats appears to change the ratio of good (HDL) cholesterol and bad (LDL) cholesterol in the body. Too many LDLs leads to heart disease and strokes and consuming plant oils are thought to cause less LDLs than saturated (animal) fats and trans-fats seem to be really bad for your LDL levels (and have been banned in many countries, but not Australia sadly). It’s not so much that trans fats are ‘evil’ fats it’s just that our bodies evolved to deal with natural plant and animals fats and they probably just doesn’t know what to do with these fancy new trans fats. I don’t think the science is all worked out yet and a lot of the focus has moved to sugar, but this is all starting to sound like a topic for another post.

Lipids and their chemistry give undergraduate biochemists headaches so if you got this far you did well . Unfortunately we’ve barely wet our toes in the subject but it is a start and we’re not aiming to be biochemists just better cooks.

Leave a comment