When I was running a medical research laboratory I was part of long running research project in Issan province in the north-eastern part of Thailand. One of the perks of working on this project was frequent trips to Thailand to work with Thai and American colleagues. My first visits were close to twenty years ago now and it became clear very quickly that my local Thai restaurants back in Brisbane had been lying to me, pulling their spice punches so to speak. On those first few trips eating actual Thai food in Thailand ended badly for me. Profuse sweating, face red like carpet burn, strong feelings of despair and, to put it politely, severe gastro-intestinal difficulties the following morning. The food was so hot. So, so hot. But, despite these difficulties I loved Thai food and I kept eating it. Over time I got better but not by much. Even now any public consumption of proper spicy food requires a good supply of napkins if I’m to get away with any dignity. But I don’t care I do it anyway.

I tell you this not for sympathy but to highlight the absurdity of humans eating chillies. Chillies are specifically designed to be toxic to mammals. The mammalian digestive systems destroys chilli seeds which is dead end as far as the chilli plants are concerned. What chilli plants want is for birds, whose digestive system is kinder, to eat their chillies and disperse the seeds far and wide propagating the next generation of chilli plants. So chilli plants made the chilli toxic to mammals and harmless to birds. The strategy almost worked. Birds eat chillies with zero side effects and all mammals avoid chillies like the plague. All mammals, that is, except one absurd, bloody-minded species1. Yes I’m talking about us, humans did not take the hint, instead we made the toxic fruit of the chilli plant the foundation of some of out most popular cuisines. In a giant ‘screw you’ from humans to chilli plants, chillies are now one of the most consumed food stuffs on the planet. There’s no accounting for crazy.

The human relationship with chillies becomes even weirder when you consider that both tomatoes and potatoes, also new world imports that are now seen as staples, were at first treated with suspicion and weren’t widely accepted for decades or even centuries after their introduction. Chillies on the other hand spread like wild-fire. When chillies arrived in the old world from South America in the late 16th century, instead of people recoiling in horror from these devil fruits, it took about five minutes for them to become an integral part of old world cuisines. Can you imagine Indian, Sri Lankan, Spanish, Chinese, Thai or Korean food without chillies? So quickly and so thoroughly were chillies incorporated into our old world cuisines that it seems like we never didn’t have chillies.

There was some precedent for chillies in the old world. Before the arrival of chillies pepper was used to add spice to food and, as we’ll find out, pepper spice is similar to chilli spice. Pepper was a big business in the 16th century so there was already a taste for spice in the old world and chillies, being much easier to grow, were probably seen as a cheaper, easier pepper. The difference is that chillies, in terms of horrific side effects per pound, are very much more potent than pepper. But this potency in no way deterred their rapid incorporation into old world cuisines. Our ancestors clearly saw that for spiciness chillies were pepper on steroids and considered that a feature not a bug.

The magic ingredient that give chillies their potency is capsaicin. You’ve probably heard of capsaicin before and that’s because it is famously responsible for almost all the noxious effects we associate with chillies. Capscaicin is a small, colorless, hydrophobic and highly pungent molecule that is synthesised in the spongy membrane that supports the seeds inside the chilli. Contrary to popular belief, capsaicin is not found in the seeds but is mostly found where it is made, in this spongy membrane (confusingly called the placenta).

Capsaicin causes it’s effects by binding to cell surface proteins that are a part of the bodies nociception system (a fancy way of saying ‘pain sensing’). This system senses pain and alerts our brain when something bad is happening to our bodies. In particular it binds to a protein heat receptor called TRPV1 and by doing so it essentially dupes our body into thinking that we are experiencing noxious levels of heat, basically that we are burning. Usually capsaicin meets TRPV1 in the mouth after we eat spicy food, though anyone who has accidentally rubbed their eyes after handling chillies has learnt that TRPV1 receptors are lurking all over our body.

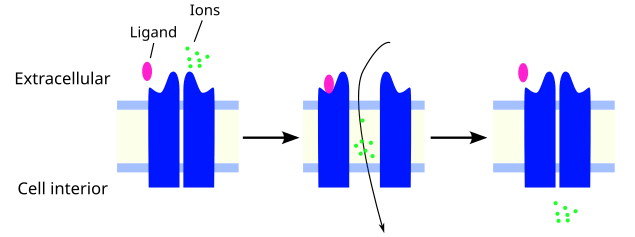

To understand how capsaicin works it’s magic we need to get a handle on how cells sense and respond to their environment and the role that a receptor like TRPV1 plays in that process. All cells are bristling with surface proteins stuck in their outer membrane. Many of these proteins are common to all cells but every cell has a subset of surface proteins that are specific to that type of cell and that are tailored to the function that that cell performs in the body. Many of these proteins can interact with exogenous molecules or are sensitive to environmental conditions and will initiate some type of cellular response when activated. Cell surface proteins like these are grouped into a broad group called receptors. There are many different types of receptors but the important ones for capsaicin bioactivity are called ion channel receptors.

An ion channel is a receptor that, when activated, will open and allow charged molecules, or ions, to enter the cell. Ion channels make nerve impulses possible by enabling the propagation of an electrical potential along neurons to the brain (and vice versa). TRPV1 sits on the surface of a sensory neuron and if it is experiencing a temperature greater than about 40C/104F it will open and the influx of charged ions will kick off a signal to your brain. This initial signal in turn triggers a bunch of downstream responses designed to protect our body from excessive heat (sweating and blushing for example). When capsaicin binds to TRPV1 it causes the exact same response as if the receptor was detecting heat and the body responds appropriately. To a chilli eater this makes intuitive sense, when we eat chillies we use the language of heat; our mouths burn, we flush, we sweat and we experience all the ‘symptoms’ of heat and that’s because our body has been duped into thinking it is experiencing noxious heat.

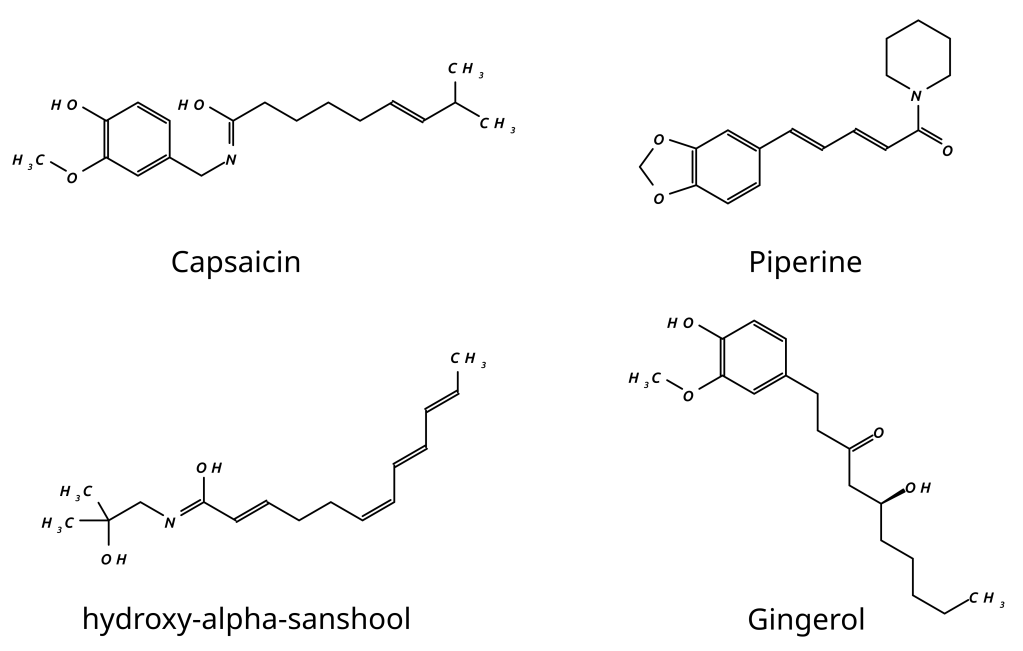

A lot of our therapeutic drugs also target ion channels, and other types of receptors, and the science of pharmacology is what helps us describe and quantify the kinetics of drugs binding to receptors. Capsaicin, for example, has a high affinity for TRPV1 (it binds tightly to the ion channel) and a high efficacy (it produces a large response for a given dosage). This explains why chillies have a strong effect that lasts for a comparatively long time, on average capsaicin is stuck in the receptor making it hard to wash away. Black pepper has a similar activity to chillies and this is because it also contains a molecule, called piperine, that binds TRPV1. But piperine has a different structure and it elicits a much less potent TRPV1 response. These binding and response kinetics also explain the responses we have to other molecules from the same family we find in our food. For example gingerol, from ginger, hydroxy-alpha-sanshool, from Sichuan peppers, and vanillin, from vanilla, all bind to TRPV1 in ways that elicit greater or lesser responses. Vanillin, for example, is a very weak agonist of TRPV1 (an agonist activates a cell receptor and an antagonist deactivates it) which is why we don’t associate vanilla ice cream with chilli burn.

Binding kinetics also informs the constant internet debate about the best way to alleviate chilli burn. If you get on the internet there are a lot of opinions but it has been studied to some extent and current scientific opinion backs up the idea that drinking milk is the best way to get rid of chilli burn. Traditionally it was thought that because capsaicin is hydrophobic a higher fat content would enhance it’s solubility (for an in depth look at why this is so see the emulsions post). But more recent work suggests casein, a milk protein and emulsifier, interacts with capsaicin and prevents binding to TRPV1. Sweetness has also been shown to reduce chilli burn, the mechanism for this is not well understood but it could be that there is a chemosensory link between sweetness receptors and TRPV1.

On the internet acid is regularly mentioned as a way of alleviating chilli burn and I’m a little bemused how this works. The usual explanation is that ‘acid neutralises capsaicin because it is alkaline’ and I’m not too clear what that actually means. Empirical evidence suggests acid isn’t a good remedy, in at least one study carbonated beverages, that increase the acidity of the mouth, were the worst at alleviating chilli burn (you can read it here). Even more damning for acid is that low pH (which means high acidity) is actually another activator of TRPV1, like capsaicin or heat. This means that rather than helping, acid could actually be contributing to the chilli burn. Bodies are complicated things though and if acid works for you then go for it.

This science can also help us out a bit when trying to fix an over-spiced dish. If you’ve added too much chilli, my first move would be to add some milk or yogurt. We’ve seen that the milk protein casein seems to be the best at alleviating chilli burn and luckily casein is heat-resistant and will generally survive the cooking process. By adding milk or yogurt some of the capsaicin in your dish will be bound to casein which means it wont bind to your TRPV1 receptor. Fats and oil might work, capsaicin will be dissolved in the fatty part of the food and may be less likely to interact with TRPV1. Adding more fats and oils isn’t normally something you want to do but butter could work and in things like Thai curries you could add more coconut milk. Finally, as we saw above, sweetness helps reduce chilli burn so add some sugar.

The picture I’ve painted of capsaicin so far is pretty simple, it triggers pain receptors and that’s why it burns. But like most things in biology the full story is much more complicated. There is not enough space here to go into all these complications but there are a few things worth noting. Firstly, as any chilli eater knows you seem to get better at eating chilli over time and there is a biological basis to this. From the very first mouthful of spicy curry biochemical process are triggered that immediately start reducing TRPV1s sensitivity to capsaicin. When TRPV1 is activated the receptor cell sends the “I’m burning” message but it then makes it harder to send the message again. This is a pretty common mechanism in neurons to avoid excessive receptor stimulation though. To be honest though, this rapid and transient desensitisation doesn’t seem to help me that much when eating spicy food.

Apart from this acute desensitisation, capsaicin also exhibits tachyphylaxis. Tachyphylaxis is a pharmacological term for when a drug rapidly stops working after a single high or repeated doses of the same concentration. So when repeated doses of capsaicin are administered (or eaten) TRPV1 receptors become desensitised to capsaicin and this desensitisation can last for days or even months. Why this happens with capsaicin is poorly understood but it has led, paradoxically, to a lot of interest in capsaicin as a treatment for chronic pain, especially for neuropathic pain (pain caused by damage to the nervous system). For us chilli eaters though it explains why we get better at eating spicy food over time. If you regularly eat spicy food you’ll induce tachyphylaxis to capsaicin and be able to eat spicy food with less discomfort.

The final thing we should consider is the question I started with. Why do humans like eating chillies even though they do horrible things to us? I’d love to say I have an answer to this but the science is inconclusive. There are plenty of theories though. Some theories focus on human psychology. For example we eat chillies as way of expressing machismo, anyone who has seen professional chilli eating competitions or even drunk friends daring each other to eat hot chillies would agree with this. Similar to this is the idea of eating chillies as low-risk ‘risk-taking’ behaviour and there have been studies that suggest that chilli consumption is highest amongst those with sensation seeking personality traits (you can read one of these studies here).

Other theories focus on physiological factors. The sweating caused by capsaicin could have driven the popularity of chillies in hotter climates (the ‘capsaicin-as-air-conditioning’ theory). Consumption of capsaicin also causes endorphin release as part of the bodies response to perceived tissue damage. Endorphins target opioid receptors, the same receptors targeted by heroin and morphine, and could thus provide a natural high that could drive a continuing fondness for chillies (the ‘capsaicin-as-a-drug’ theory).

Yet other theories suggest that the mild anti-microbial activity of capsaicin may have provided a way of preserving food (the ‘capsaicin-as-a-refrigerator’ theory). Finally, it has been suggested that inflammation in the mouth, again caused by the bodies response to perceived tissue damage, could make the oral cavity more sensitive to other sensations. This could make eating a spicy dish more intense as our sensation of the other ingredients such as salt, acid, alcohol and carbonation is increased. Our mouth becomes so sensitive that it makes, as Harold McGee puts it, ‘inhaling room-temperature air like a refreshingly cool breeze’.

None of these theories explain everything and some of them explain very little so I suspect it’s a combination of the individual and a whole bunch of different factors that contribute to our love of chillies. From a genetic viewpoint about 18-50% of the variation in capsaicin sensitivity in humans can be explained by the genetics of the individual so those who really like chillies might just be genetically predisposed to liking them. We don’t really know to be honest. The only thing we do know is that we complicated, boastful and confused humans will continue eating chillies for as long as there are chillies.

Other stuff

Further reading

I’ve really only scraped the surface of capsaicin but it’s a start and this blog is about food science not pharmacology so hopefully we are bit better armed when we are using chillies in the kitchen. If you disagree and want some more capsaicin knowledge this review is a good place to start. It is very long though.

Footnotes

- OK – that is not quite correct. There is one small mammalian species that lives in the forests of South and Southeast Asia called the Tree Shrew that can and does eat chillies. This was only discovered in 2018 (you can read the paper here) but Tree Shrews have a genetic mutation in the TRPV1 receptor that makes them much less susceptible to capsaicin. So this species is more like birds in that they are not that bothered by capsaicin. The point that humans are definitely bothered by capsaicin but continue to eat it stands. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Jason Mulvenna Cancel reply