Humans have an almost unlimited capacity to endure other people’s suffering when there are large sums of money to be made1. For proof of this we need look no further than our history books. History is littered with examples of humans behaving appallingly to their fellow human while in pursuit of a quick buck. Notable for both the quantity of riches and the badness of behaviour, the spice trade is perhaps the best historical example of the liberating effect of money on human morality. Lasting for over 3,000 years, the trade in spices from their origin in the east to markets in the west featured genocide, mass murder, piracy, slavery, fraud, colonial conquest and countless other examples of bad behaviour that visited suffering on many and riches on a few.

What inspired a lot of this bad behaviour was the scramble for monopolies. Traders wanted to create and maintain monopolies on their spices. There was always a high demand for spices, so if a spice trader could establish a monopoly, they would control the supply and so the price. The riches would then flow. It’s the same wet dream Silicon Valley tech bros have when searching for patentable tech. In the spice trade, instead of patents, monopolies could be established by using any means possible to control either the source of the spice or the routes that were used to get the spice to markets. In the best case scenario you would control both.

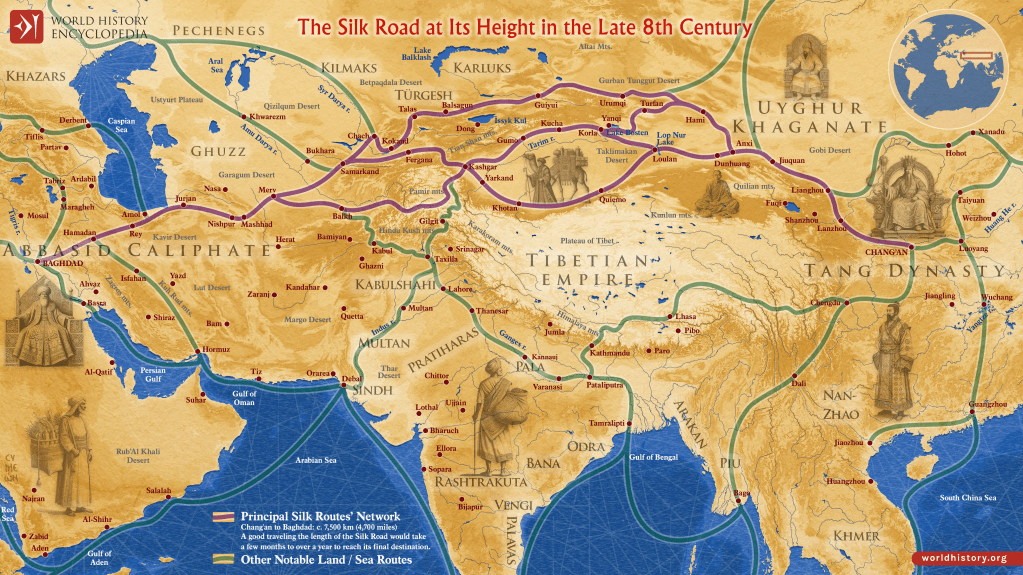

For example, the undisputed masters of controlling spice routes were the Arab traders. From around the 7th century, Arab traders managed to establish control over the routes that brought spices from the east to Europe. This gave them a near monopoly on the supply of European spices for the next 700 years. The money they made helped fund the opulence of the Islamic golden age and transformed Venice, which itself established a near monopoly on trade with Arab countries in Europe, from a cluster of huts to one of the most powerful maritime republics of the Middle Ages. It was only when the Portuguese worked out how to sail around Africa, and get their own spices, that the Arab monopoly was broken (and replaced with Portuguese monopolies).

For the Arab traders, geography was an important contributor to their monopoly. But sometimes biology lent a helping hand to budding spice monopolists. This was certainly the case when it came to the monopoly the Spanish held on vanilla. A new world spice, vanilla is the fruit of the vanilla plant, Vanilla planifolia. An unusual plant, in more ways than one, it is an orchid, that grows as a vine, and it is the only orchid whose fruit we use as a food. It was cultivated by the Totonac people, who lived about the Gulf of Mexico, for about 2,000 years until they were conquered by the Aztecs. When the Aztecs, also fans of vanilla, were conquered by Cortez2, vanilla was taken back to Europe where it quickly became the world’s favourite flavouring, arguably a title it still holds today.

Although paling in comparison with the silver and gold that they plundered from the New World, the popularity of vanilla in Europe meant that vanilla turned out to be a nice earner for the Spanish. What really made it profitable was that they had a monopoly on vanilla, they controlled the supply, but, importantly, they didn’t have to lift a finger to protect their monopoly. The Spanish hadn’t been able to prevent vanilla plants being taken from Mexico and they were available elsewhere in the world. But the vanilla plant would only fruit in Mexico. Everywhere else the plant would flower but no fruit would develop. Nature, it seemed, was Spanish when it came to maintaining a vanilla monopoly.

This was a real stroke of luck for the Spanish. The Dutch, by comparison, had to go to a whole lot more trouble to maintain their nutmeg monopoly. They committed genocide in the Bandas Islands, they shipped the seeds in lime to prevent germination, and they expended significant military force to protect their nutmeg crops and to destroy trees on islands they didn’t control. The Spanish, thanks to biology, maintained a monopoly over vanilla for three hundred years, from the 16th to the 19th century, without any of the questionable behaviour normally required of spice monopolists3.

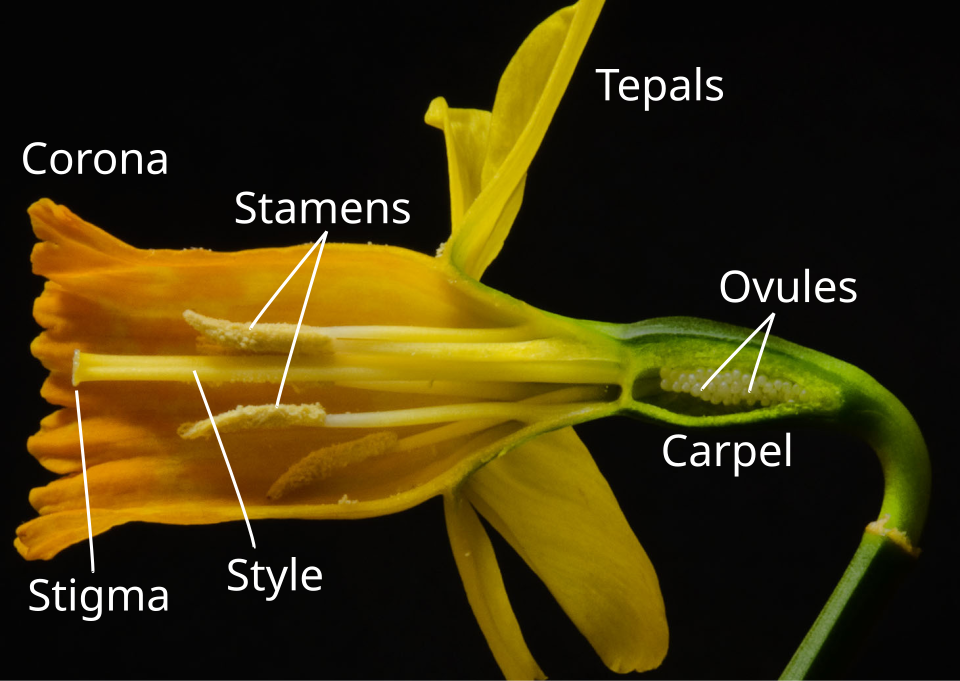

What was really helping the Spanish were some peculiarities when it came to the pollination of the vanilla plant. In flowering plants, called angiosperms by botanists, pollination is the process whereby an animal, often a bee, transports pollen, a kind of mobile plant testicle4, from the anther (the male organ) to the stigma (the female organ) of, usually, another flower. Once fertilised, a flower will develop into a fruit that contains the seeds that will grow into new plants. The vanilla pod, that we use in our cooking, is simply the fruit of the vanilla plant.

The flowers of the vanilla plant, like 90% of other angiosperms, contain both an anther and a stigma. That is, they contain both male and female sexual organs and are hermaphroditic5. Because they possess both pairs of sex organs, hermaphroditic plants are potentially able to fertilise themselves, and many do. This reduces the dependency on pollinators and makes fertilisation a more certain prospect, but it can be a dangerous strategy as it reduces genetic diversity which can have dire consequences for the survival of a species (see the post on bananas for a discussion of this).

For this reason some hermaphroditic plants have evolved ways to prevent self-pollination. Plants can employ self-incompatibility mechanisms, where the stigma rejects pollen from the same plant. The anther and the stigma can mature at different rates so that the same flower is not producing pollen when the stigma is receptive. And, sometimes, they just keep the anther and the stigma far away from each other to minimise the chance that pollen from the same flower will come in contact with the stigma.

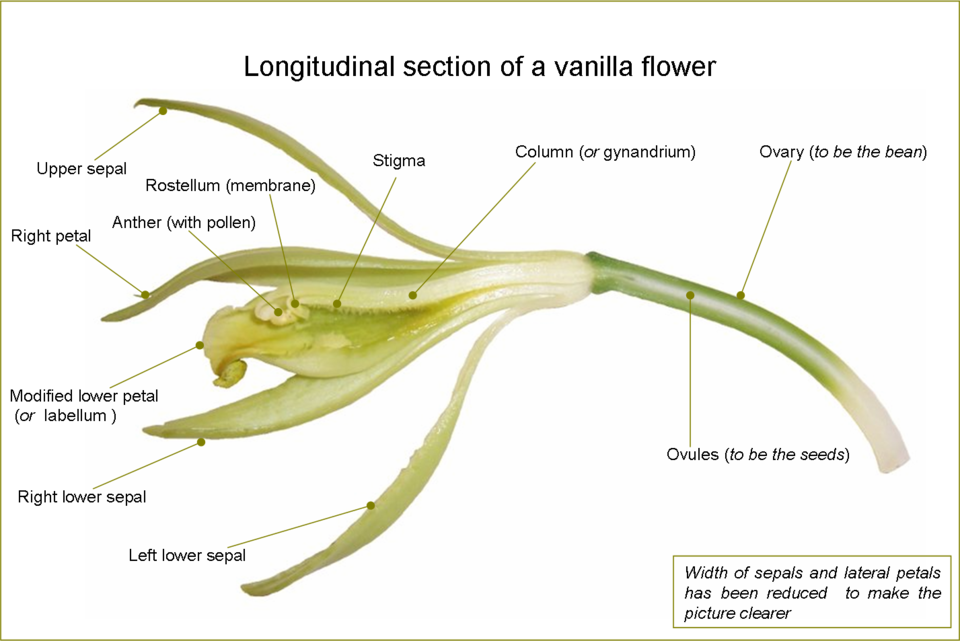

The vanilla plant prevents self-pollination by physically separating the anther and the stigma of the same flower with a membrane, called the rostellum. This makes it very difficult for the vanilla plant to pollinate itself. In a natural setting, the only way that a vanilla plant can be pollinated is by a pollinator.

Crucially for the Spanish monopoly, the only pollinators that can bypass the rostellum are small stingless bees from the Meliponia genus that only live in Mexico. Without Melipona, no vanilla plant outside of Mexico could produce fruit because no other bee was capable of dealing with the rostellum and getting to the pollen. This is a classic case of two species co-evolving over time: the vanilla plant to prevent self-pollination and Melipona bees to develop the smaller size and strength necessary to obtain the pollen.

Given that Melipona were highly specialised to their local environment and unlikely to establish themselves anywhere else in the world, it seemed the Spanish monopoly was secure. But there was a small chink in their armour. The vanilla plant could self-pollinate, it just never happened naturally because the rostellum was too formidable a barrier. But, with the large amount of money at stake, you can bet that people were trying to work out how to get vanilla pollen onto vanilla stigmas.

The French, in particular, were especially keen to break into the vanilla trade. But, even after botanists worked out why the vanilla plant wouldn’t flower outside Mexico, no one could come up with a economic method of forcing self-pollination. The flowers were too fragile to mess around with too much and if it took too long to manually self-pollinate vanilla you could never pollinate enough plants to make it a viable economic option.

Oh, and there was another problem. Vanilla plants flower for a single day and the flowers only open for 8–12 hours, from early in morning to the afternoon. If not pollinated during this time they will wilt. So, growers were also on the clock. Using manual pollination to produce a vanilla crop meant an incredibly fiddly job had to be performed on a large number of plants in a very short period of time. For a long time, no one could develop a method for manually pollinating vanilla plants that was simple and quick enough to cultivate vanilla plants without Melipona bees and so the Spanish monopoly held.

Ultimately it was a twelve-year old slave boy, called Edmond Albius, on the French-controlled island of Réunion who worked out a method for pollinating the vanilla plant. In 1841, he worked out that if he used a small stick to lift the rostellum and pushed the anther and the stigma together with his thumb it would pollinate the plant.

The technique, which is still the primary way of pollinating vanilla today, revolutionised the industry, broke the Spanish monopoly and turned Réunion, and the nearby island of Madagascar, into major centres of vanilla production for the French. This was the spice trade though, and Edmond Albius, far from profiting from his breakthrough, died penniless in 1880. I’m sure he’d be comforted, or maybe not, by the many statues of him to be found on Réunion today.

Though the monopoly was broken vanilla remained the second most expensive spice, after saffron. Producing vanilla was, and still is, a lengthy, arduous and time consuming process. Apart from pollination, the pods need to be extensively processed to develop flavours and become the vanilla bean we would recognise in our kitchen. Today, most natural vanilla comes from Madagascar (sometimes called Bourbon vanilla, ultimately named so after the French ruling house of Bourbon), Mexico, Indonesia and Tahiti. Yet, even with these centres of vanilla production, only 1% of the vanilla flavouring used in the world actually comes from a vanilla plant.

How this situation came to be is an interesting story in itself; the story of vanilla is so much more than just its role in the spice trade. But the story is way too big for a single post on this blog. So, in part two, we’ll get back into areas I’m much more qualified to talk about, the biochemistry that demands a complicated fermentation and curing process before the vanilla pod yields its flavour, the chemistry behind the flavour of vanilla, and how, once the chemists got involved, the monopoly of the vanilla plant itself over vanilla flavouring was broken.

Footnotes

- This is considered by some to be the way of the world, but these people are rarely the ones doing the actual suffering. ↩︎

- I feel that Cortez, surely the possessor of the prototypical spice trader personality, would have done very well in Silicon Valley. ↩︎

- Not that the Spanish were not indulging in very morally questionable activities elsewhere at the time. It’s just they didn’t have to take time to commit additional morally questionable actions when it came to maintaining the vanilla monopoly. ↩︎

- Technically pollen is a living multicellular organism called a gametophyte. The gametophyte, once it gets to the right place, will germinate and produce sperm cells. This makes plant sperm more resilient as pollen can suffer adverse conditions, such as a lack of water, and remain viable. Human sperm, for example, can’t survive in the environment until it finds itself an egg, a good thing for woman I’d say. For simplicities sake pollen is often called plant sperm but a more accurate simile to mammalian reproduction would be to say that pollen is more of a mobile, free-living testicle. ↩︎

- There is some terminology around plants and their sexual organs. Dioecious plants are those where individual plants have either male or female reproductive organs, just like humans. Monoecious plants are those where individuals possess both male and female reproductive organs but, in the flowering plants, they can occur in separate flowers. Hermaphroditic plants are monoecious but have both male and female sexual organs in all their flowers. This means that all hermaphroditic plants are monoecious but, not all monoecious plants are hermaphroditic. ↩︎

Leave a comment