For anyone with an even cursory interest in health and nutrition it has become very hard to avoid the gut microbiota. The collection of bacteria, and other microbes, that we all carry around in our gastrointestinal tract is proving to have an influence on our health and well-being unimaginable even twenty short years ago. Our microbial friends help us with digesting our food, they shape and regulate our immune system, they protect us from other harmful microbes and they can even influence our mental well-being via the gut-brain-axis. Given the importance of the gut microbiota it stands to reason that an imbalance in its constituents, a state known as dysbiosis, can negatively affect our health and sure enough the gut microbiota has been associated with more than a few diseases. The aetiology of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity and several cancers can all involve our microbiota in some way or another.

Although there is much left to learn, what we now know about our gastrointestinal microbes is impressive considering that less than 400 years ago we had no idea that microbes even existed. In fact, for most of human history we were completely oblivious, unaware that we share our world with a multitude of microorganisms. If we ignore the theory of panspermia1, the story of microbes goes back to the origins of life on earth, some 3.8 billion years ago2, and Homo sapiens, and their microbiota, have been knocking around for the last 300,000 of those years. This is a lot of time for us to remain ignorant of the vast world existing just beneath the limits of our perception. We have always been aware of microbial activity: the rotten food, the bad smells, the disease, the gangrene and, more beneficially, our fermented foods; but until the late 17th century we had no inkling that the common cause of these phenomena were microbes.

The problem, of course, is that it’s hard to understand something unless you can see it and to discover the microbial world we first needed the technology that would allow us to magnify that which we couldn’t see with the naked eye. Around 1670 a Dutchman named Antonie van Leeuwenhoek started producing microscopes that were good enough to do just that. A draper, or cloth merchant, by trade Leeuwenhoek started playing around with lenses so he could better view the quality of thread in his cloth. The single-lensed microscopes he came up with were such an improvement on the existing microscopes3 that he brought into focus not only his threads but a whole microscopic world formerly hidden to us. A world that he then started to systematically explore.

Although he kept his lens making techniques a closely guarded secret Leeuwenhoek, who lacked any scientific training and never published a formal research paper, communicated his discoveries in a long series of letters to the Royal Society in London. He described the microscopic structure of a bee’s mouth parts, he examined and microscopically described a louse, he observed and correctly identified red blood cells, and he described sperm from humans and other animals4. In many of his samples: rotten water, scrapings from his teeth, water from ditches and his own diarrhoea, he observed small moving objects. Working on the principle that if it moves it’s alive he named these microscopic life forms “diertjes”, or, in English, “animalcules”. Leeuwenhoek had not only discovered microbes, but by describing animalcules from his own stool I would say he had discovered the gut microbiota5.

Leeuwenhoek did meet with some resistance to his work. His lack of formal scientific training counted against him and his insistence on keeping his lens making techniques a secret also caused some grumbling. Robert Hooke, the “English Leonardo” who was also interested in microscopy, fretted that such an important technique being in the hands of one man was bad for science6. But Leeuwenhoek was always happy to entertain the scientists who flocked to his workshop, eager to view the world using his microscopes and ultimately his discovery of microbes was accepted. Now he is known as the “Father of Microbiology” and, as an inspiration to young scientists everywhere, in 2004 he was voted the fourth most important Dutchman in history.

I’d like to say that given Leeuwenhoek’s work we quickly made up for lost time and microbiology immediately took off but that wouldn’t be quite right. Microscopes were expensive and hard to get and a lot of time was wasted on dead ends like the idea that microbes spontaneously generated during disease. Edward Jenner did develop the first vaccine in 1796, for smallpox, but he didn’t achieve this with reference to microbes, rather through the observation that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox, a much less dangerous disease, were immune to smallpox7. It wasn’t really until the middle of the 19th century, almost 200 hundred years later, that microbiology really got started again. But once it got started it really got going and the period between the mid-19th century and the early 20th century is known as the golden age of microbiology. In this period the breakthroughs came quick and fast and were of such importance that they changed our approach to medicine for ever.

The two giants of this golden age were Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. Between them they established germ theory, the idea that microbes cause disease, as the dominant way of understanding many human diseases (I’ve talked about germ theory in a previous post). Pasteur, probably the better known of the two today, not only conducted experiments that connected microbes to fermentation, disease and the spoilage of food but he also worked to develop practical applications of germ theory. Two of his most well-known applications being the development of techniques for removing microbes from food, what we now call pasteurisation, and the development of vaccines8 that could protect people from the microbes that cause infectious disease. Robert Koch, on the other hand, was a medical doctor who started to associate specific microbes with specific diseases. To do this though Koch had to solve a fundamental problem.

To study microbes you need to essentially grow enough of them, in a process known as culturing, so that you can perform whatever experiment you want to conduct. The problem is that many microbial samples that you come across, whether it be pond water or some sputum from a sick patient, has a community of different microbes. This makes it very hard to focus on and study a single microbe because when you culture a mixed sample you end up with a bunch of different microbes in your culture. Koch wanted to be able to expose organisms to a specific microbe, and only that microbe, so that he could associate it with a specific disease. This is very hard to do without a way of generating pure cultures.

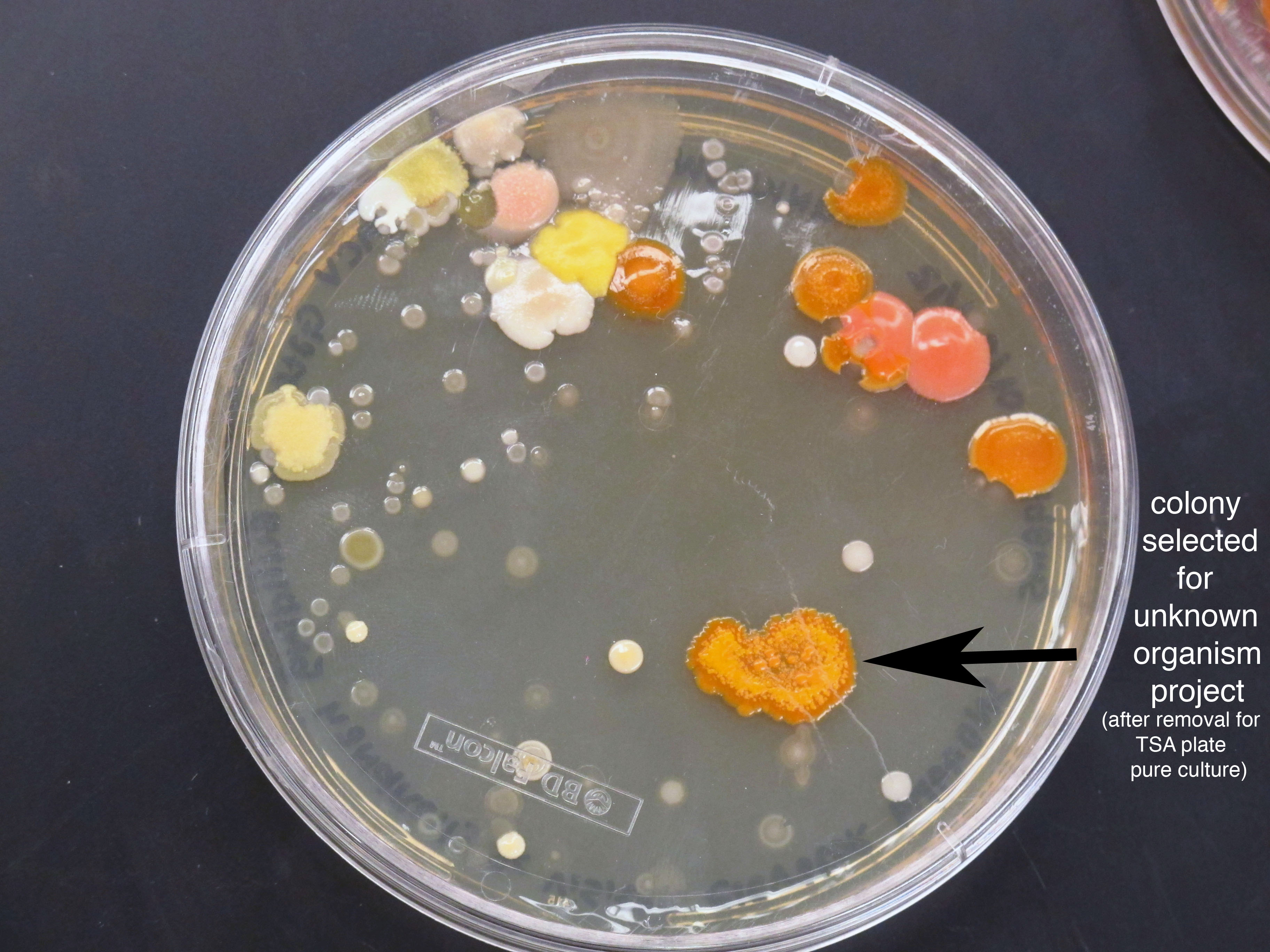

Koch, who was a meticulous researcher, developed a method of producing pure microbial cultures. To do this he took a small sample of a microbial mixture and scrapped it over a solid growth media, like agar for example9, in the hope that single microbes would be isolated on different parts of the media10. Small microbial colonies would then grow in which the microbes in the colony were all the descendants of the one ancestor microbe. You could then take these small colonies, culture them and end up with a pure sample. Using this method Koch was able to isolate and grow specific microbes and show that they caused a specific disease, by injecting them into animals for example. Using his culturing techniques Koch discovered the species of microbe responsible for tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax. Others, using his techniques, discovered many more and the culturing methods he established are still used to this day.

In the great tradition of famous scientists hating each other, Koch had a long running feud with the Pasteur. Apart from Koch being German and Pasteur French, they were a contrast in styles as well as ideas. Pasteur, who was probably more interested in applications of germ theory than a systematic survey of microbial disease, used liquid cultures in which it is very difficult to get a pure sample of a specific microbe. I don’t think this mattered too much to Pasteur, he was trying to develop vaccines by weakening or, in technical terms, attenuating microbes. Attenuated microbes wouldn’t cause disease but they would prime the immune system of the recipients, providing protection when they encountered the real microbe11. Pasteur didn’t really need a completely pure culture for this; a few extra types of bacteria wouldn’t cause too many problems. In fact, Pasteur got the idea for this method after he left a sample of cholera out over a weekend and the exposure to the air attenuated the microbe.

To Koch, who probably never accidentally left anything out over the weekend, this type of thing was an anathema. Koch believed that Pasteur wasn’t being rigorous enough and he didn’t mind saying it. Koch also claimed that because Pasteur wasn’t a doctor he had no basis for understanding human disease. It certainly didn’t help that their interests in anthrax overlapped and that Pasteur’s anthrax vaccine, that Koch had publicly said wouldn’t work, ended up working in a public experiment on sheep12. Words were exchanged at scientific conferences and the rivalry between the two ended up becoming a matter of national pride for the French and the Germans. While I wouldn’t say it was one of the causes of WWI it was definitely one of the better scientific feuds that we’ve had the pleasure of witnessing.

Regardless of what they thought of each other, Pasteur and Koch both gave us the weapons we needed to start fighting back against infectious disease. Throughout human history infectious disease had been far and away the most common cause of mortality. Mostly because of infectious disease childhood mortality had hovered around 50% for most of history; that is only one out of every two children made it to adulthood because of infectious disease. It wasn’t really till the 1950s that infectious disease was eclipsed by other types of mortality. This victory was won thanks to germ theory and the consequent improvements in sanitation and hygiene and the development of antibiotics and vaccines13. Before germ theory people would sicken and die and those left behind would not have a clue what had happened, now we knew and we could start fighting back.

Despite the breakthroughs of germ theory, when it came to characterising our gut microbiota there were problems. It turned out that some microbes were not easily cultured; we couldn’t work out what conditions were suitable for their growth and so we couldn’t easily study them. We were kind of lucky that the disease-causing microbes that Pasteur and Koch worked with, those causing cholera and tuberculosis for example, had been relatively easy to culture but many bacteria were a lot harder to please. The gut microbiota in particular were a fussy lot. We know now that this is because most of the microbes in our gut are anaerobic, that is they grow in the absence of oxygen, but this meant that research could not really move forward until we had worked out new ways to culture these anaerobic microbes.

People were still thinking about intestinal microflora though. Pasteur, and other eminent scientists such as Élie Metchnikoff, a groundbreaking early immunologist, and Theodor Eschericha, more on whom below, all believed that our gut microbiota would prove to have an important role in normal human physiology and in disease. Metchnikoff and the inventor of corn flakes, John Harvey Kellogg, were both advocates of a theory known as autointoxification in which toxic products from our intestinal microbes are thought to re-enter the body and cause disease. Although the theory is now mostly discredited14, Kellogg came up with an entire holistic approach to the imagined problem, prescribing yoghurt enemas15, laxatives, vegetarianism, sexual abstinence and other more or less weird practices designed to clear intestinal flora. Some of his treatments actually sound pretty reasonable, exercise and giving up smoking for example, but a broken clock is right twice a day and not a lot of Kellogg’s theories were based on solid scientific evidence.

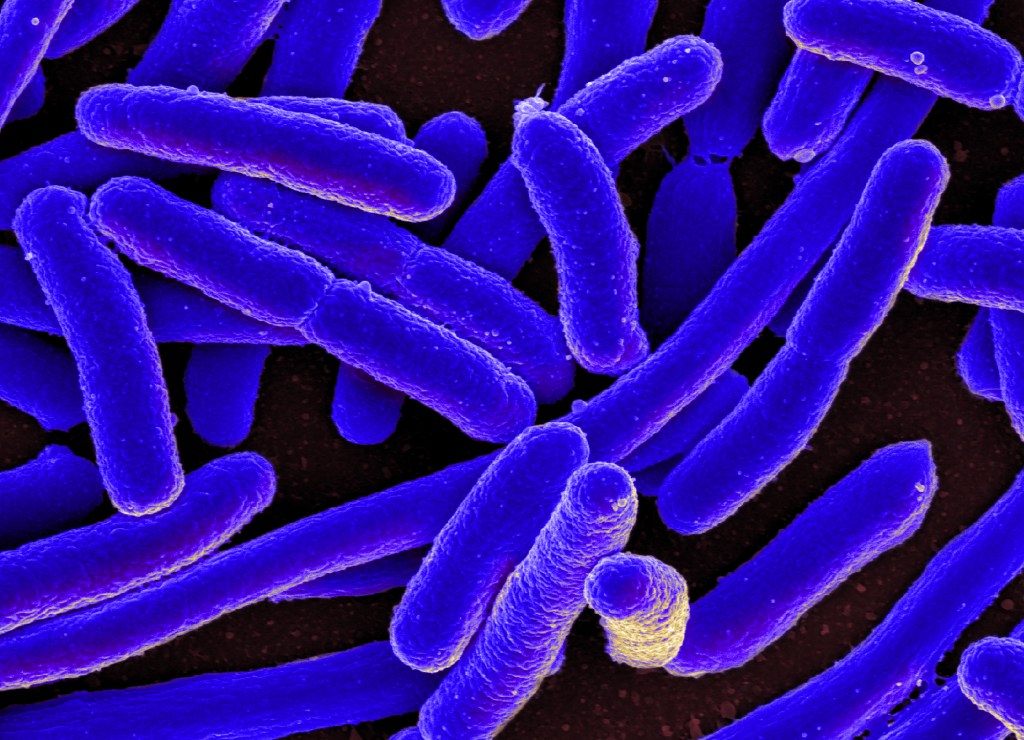

Getting back to the realm of proper evidence, in the late 19th century, Theodor Eschericha did a large amount of work on the bacterial content of infant faeces and discovered a common gut bacterium that was posthumously named after him: Escherichia coli. Most people have heard of E. coli as a bacterium that that can give you a pretty severe form of food poisoning. Although most strains of E. coli are harmless, and are a common constituent of our gut microbiota, some strains produce Shiga toxin that causes bloody diarrhoea and other severe gastrointestinal symptoms. Contamination of food with these Shiga-producing E. coli strains remains a serious public health issue16 but if you think it a bit odd that Eschericha has been commemorated by naming this feared public nuisance after him, other strains of E. coli have been the workhorses of molecular biology labs since at least the 1940s. E. coli is routinely used as a model organism and is frequently used as a tool for gene cloning and recombinant protein production17. I think Eschericha, or any self-respecting microbiologist, would be proud that their bacterium turned out to be so useful.

At the turn of the century, Henry Tissier made some advances in anaerobic culturing and discovered the Bifidobacterium genus of bacteria. Tissier also successfully used these bacteria as a treatment for infantile diarrhea, and they are still used today as common probiotics. In 1912, during WWI, another German scientist, Alfred Nissle discovered a strain of E. coli that could protect people from dysentery. A corporal deployed to an area where dysentery was common seemed to be immune to the disease and Lissle, working with the soldier’s stool, discovered the E. coli strain that inhibited the growth of pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella. Lissle cultured the strain and sold it as a probiotic called Mutaflor that you can still buy today. Lissle not only demonstrated, for the first time, that the gut microbiota can protect you from other nastier microbes but he also proved that if a microbiologist expresses an interest in your poo you should hand it over for the greater good of humankind.

This has become a long post so I’m going to leave the story here. In the second part we’ll look at how our understanding of gut microbiota took off during the 1960s, with advances in anaerobic culturing, and how DNA sequencing technology has really turbo-charged microbiome research in the last 20 years. I’ll also have a look at how the microbiome affects how health and what we can do to look after our microbial friends.

Footnotes

- One variant of this theory is that life on Earth arose from microbes that hitchhiked from elsewhere in the universe on asteroids, meteors, comets or spacecraft. To say this theory is controversial is an understatement. ↩︎

- I’m going to use the word microbe a lot here but that word is disguising a lot of variety. All life can be divided into two broad groups: the eukaryotes and the prokaryotes. The prokaryotes are what we would consider bacteria and they are characterised by a lack of internal structures, like a nucleus. The prokaryotes are further divided into two kingdoms called the eubacteria, containing most of the bacteria we are familiar with, and the archaea, who tend to hang out around ocean vents and other inhospitable areas. Every other organism is a eukaryote and we have membrane bound internal structures in our cells, nucleus and mitochondria for example. The term “protist” is a loose term referring to eukaryotes that aren’t animals, plants or fungi, many of which are unicellular. Things like amoebas, kelp, algae and plasmodium, the cause of malaria, are typical protists. Microbiologists are interested in all these organisms as well as single celled fungi, aka yeast, and viruses that aren’t considered to be a living organism. I’m going to use “microbe” for all of this diversity except where I’m describing something specific to a particular group. ↩︎

- The first microscope was developed by a father and son team, Hans and Zacharias Janssen. Though an impressive achievement the compound microscopes that followed had some serious limitations that restricted magnification to around 20 times. Not quite good enough to get a good look at microbes that just appear as dust or dirt at that level of magnification. ↩︎

- Microbiology involves a lot of bodily fluids, human and otherwise. So if you’re squeamish this may not be the essay you’re looking for. ↩︎

- Because scientific attributions can often be quite complicated it should be noted that Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit priest, actually observed “little worms” in the blood of plague victims using a microscope in 1856. He also speculated that disease could be caused by microscopic pathogens in his book Scrutinium Physico-Medicum in 1658. Despite Kircher’s accomplishments Leeuwenhoek gets all the praise because he systematically studied and experimented on his microbes laying down the foundations of microbiology. Still a bit rough on Kircher if you ask me. You could also say that Robert Hooke was the first to observe a microbe when he described the microscopic detail of Mucor, a type of fungi called a mold, in 1665. It depends if you classify Mucor as a microbe I suppose, considering it is multicellular organism. You can see why many a scientific feud has erupted over who made an initial discovery, a much more recent example of that being the fight over CRISPR technology. ↩︎

- He was probably right and you couldn’t get away hiding the details of your work like that today. Hooke was actually a great supporter of Leeuwenhoek so I’m sure that although Leeuwenhoek’s secrecy was also bad for Hooke, it was only an incidental concern. ↩︎

- Although Jenner’s achievement was a wonderful thing I would not have wanted to get too close to him as a young boy. To prove his theory, he inoculated an eight year old boy with material from a milkmaid’s cowpox sore. He then deliberately infected the boy with smallpox to see if he contracted the disease. He didn’t, which was lucky as smallpox is a serious disease with a mortality rate of about 30% (by way of contrast one estimate of COVIDs mortality rate among unvaccinated people is around 4.9%). I wouldn’t have wanted to be that boy and I don’t think you’d get ethical clearance for that experiment today. ↩︎

- As recognition for Jenner’s achievement developing the vaccine for smallpox Pasteur coined the terms “vaccine” and “vaccination” derived from Jenner’s use of vacca, Latin for cow. ↩︎

- Agar is a jelly-like substance made from red algae. It is a gelling agent much like gelatin and it is often used an a vegan alternative to gelatin. ↩︎

- In the process of developing this technique one of Koch’s assistants, called Julius Richard Petri, invented the petri dish. Another assistant, Walther Hesse, had wife called Fanny who was the person who actually suggested using agar in the petri dishes. A sign of the times perhaps, but she was never credited with the idea but you can read her fascinating story here. ↩︎

- We still use this technique today. Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, yellow fever, varicella, and some influenza vaccines, amongst others, are all made from attenuated microbes. ↩︎

- I miss the days when scientists would conduct public experiments under the eyes of the media and the world. It would make a nice change from the UFC and it would be fun watching celebrities pea-cocking around waiting for the experimental fun to get going. ↩︎

- A victory that some leaders in the Western world now seem intent on undoing. ↩︎

- A notable exception to “mostly” is auto-brewery syndrome in which microbes in the gut can start producing alcohol from carbohydrates resulting in alcoholic intoxication. Cases of this extremely rare syndrome have occurred in the UK and in the USA, though there is evidence the Japanese people may have a predisposition to the syndrome because of the common occurrence of a dysfunctional aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 enzyme in that population. ↩︎

- Well, half the yoghurt was administered as an enema the other half was meant to be eaten. Addressing the problem from both ends so to speak. ↩︎

- For example, as I write this in November 2025, there is a serious E. coli outbreak occurring in Germany, affecting hundreds of people as well as linked cases in the USA, Netherlands, Italy, and Luxembourg. ↩︎

- This author has spent more than a few hours streaking E. coli onto agar plates while trying to clone genes for bacterial expression of proteins. The distinctive smell of a lab culturing E. coli, a ‘poopy’ smell that is caused by the production of indoles by the bacterium, is not something quickly forgotten. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Teresa 何 Robeson Cancel reply