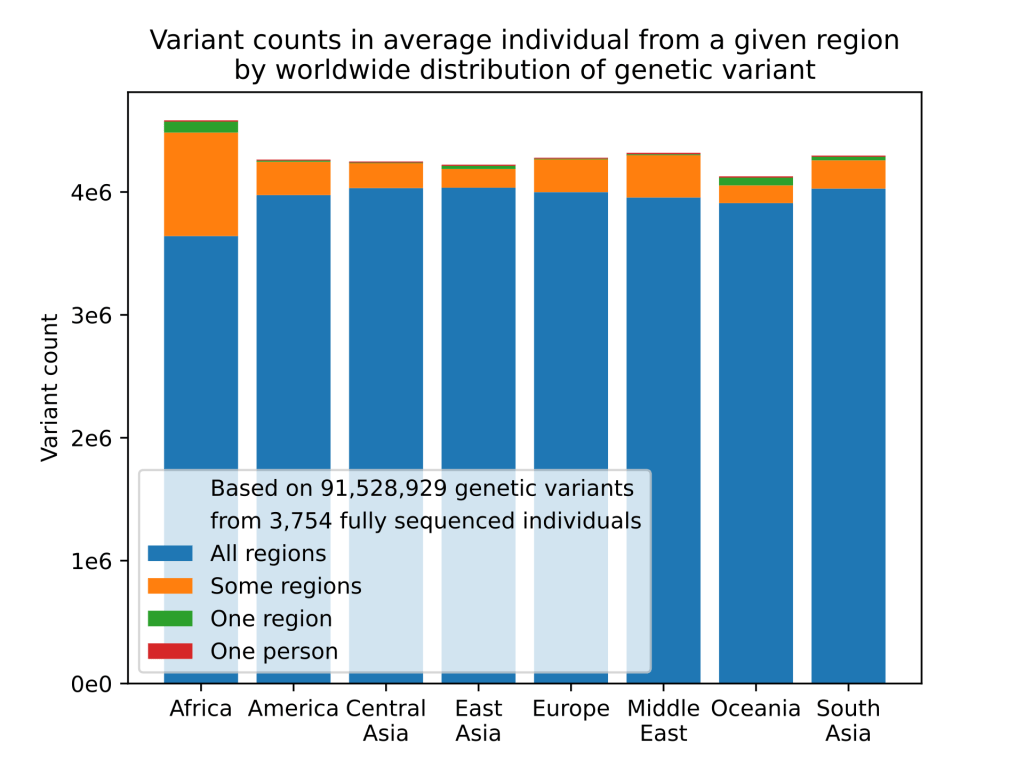

In a world that seems hell bent on pigeon-holing us into convenient advertising demographics it is worth remembering that almost every single one of us is completely unique1. Thanks to sexual reproduction and genetic recombination each of us is an experiment in what can be achieved with the raw clay of the human gene pool. Unlike a bacterium, which can have potentially trillions of genetically identical siblings, every human is alone in their unique genetic makeup. This is a great strength of our species, one of the advantages of sexual reproduction is that genetic variation provides a pool of potential solutions to problems that we, as a species, haven’t encountered yet. It provides flexibility and adaptability in the facing of a constantly changing environment.

Despite this, once a species has evolved intelligence and used that intelligence to develop modern medical science genetic variation can become a bit of a nuisance. Genetic variation, by it’s nature, means that every individual has a unique relationship with their external environment. This means that when modern medical science attempts a remedial intervention we can never be quite sure that everyone will react the same way to that intervention. This is why getting governmental approval for new drugs is so rigorous. Testing a new therapeutic on 100 people doesn’t give you any idea if, among the billions of humans, it’s going to harm some people with a specific genetic makeup. Even if it only harms 0.1% of people, that’s still 8 million people worldwide. Drugs like thalidomide, mercaptopurine, clopidogrel and even codeine have all taught us the truth of this.

Genetic variation also makes it hard for scientists studying how diet affects our health and well being. I’ve criticised observational nutritional studies quite a bit on this blog. My complaints mostly coming down to the over-reliance on self reporting and the lack of randomised design introducing the potential for confounding factors. Human genetic variation is one of these confounding factors. Without a clear understanding of the interplay between our food and our genetics it is very hard to tease out effects that are specific to our diet and make recommendations suitable for everyone in society. Does a particular dietary habit cause illness in all people or is it just a subset of people with a specific genetic makeup?

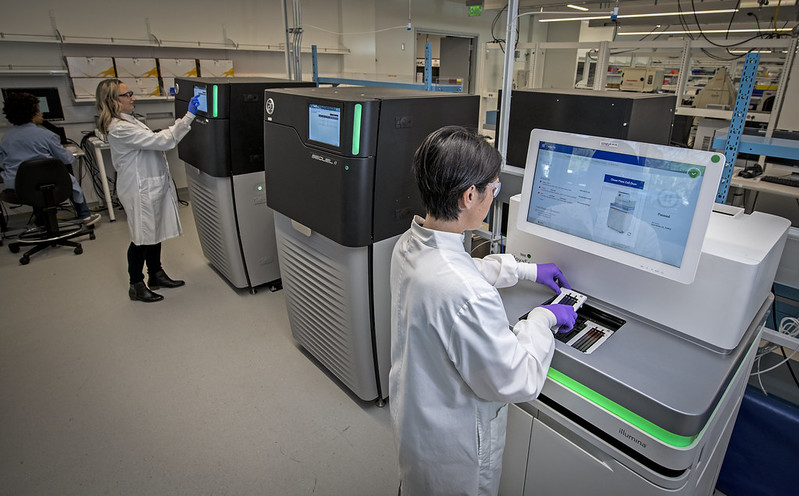

This is not an original idea and over the last decade or so a new field of science has arisen looking at exactly this issue. The way that diet and genetics interact. How does diet affect the expression of our genes and how do our genes influence the effects of our diet on our health? This new field is called nutrigenomics and it is really a product of technologies like genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics that have allowed us to start profiling the genetic variation possessed by individuals. This is very powerful as it potentially allows us to start taking into account the genetic makeup of individuals in nutritional studies and eventually tailoring dietary interventions to the genetic signature of each individual.

The history of humans experience with vitamin D is a brilliant illustration of these ideas. Vitamin D refers to a group of five different fat-soluble secosteroids2, the most important for our health being D2 (also called ergocalciferol) and D3 (or cholecalciferol). Vitamin D is considered an essential vitamin (i.e. one that we need but can’t make for ourselves) but it is interesting because, unlike the twelve other essential vitamins, humans do actually have the capacity to synthesise vitamin D3. In the lower levels of our epidermis, upon the absorption of UV-B from sunlight, humans can synthesise vitamin D3 in greater quantities than we can normally obtain from our diet.

So if we can make vitamin D in sufficient quantities why do we classify it as an essential vitamin? Well the catch is that we need the UV-B and in the modern world we often do not get sufficient exposure to sunlight to make enough vitamin D. The culprit can be climatic, parts of the world that experience low sunlight are obviously problematic, but vitamin D deficiency is also common in areas such as the Middle-East, Asia, Africa and South America where there is normally loads of sunlight. This seemingly counter-intuitive situation can be partly explained by our lifestyles: we wear more clothing, public health guidelines often recommend restricted exposure to sunlight to avoid skin cancer and sunlight can be blocked by air pollution.

Another important factor is that melanin in the upper layers of the epidermis can limit the amount of UV-B that can be used for vitamin D synthesis. When combined with modern lifestyles darker skinned people can be more vulnerable to vitamin D deficiences and worldwide, it is estimated that more than one billion people are deficient in vitamin D. This current situation is something of a reversal of what occurred over the course of our evolution. Current theories suggest that dark skinned ancestors who moved into areas such as northern Europe were put under severe evolutionary pressure because the lack of sunlight in these climes favoured lighter skinned individuals who could synthesise sufficient vitamin D. This explains my pasty complexion and propensity to burn when exposed to minute amounts of sunlight, my ancestry is northern European.

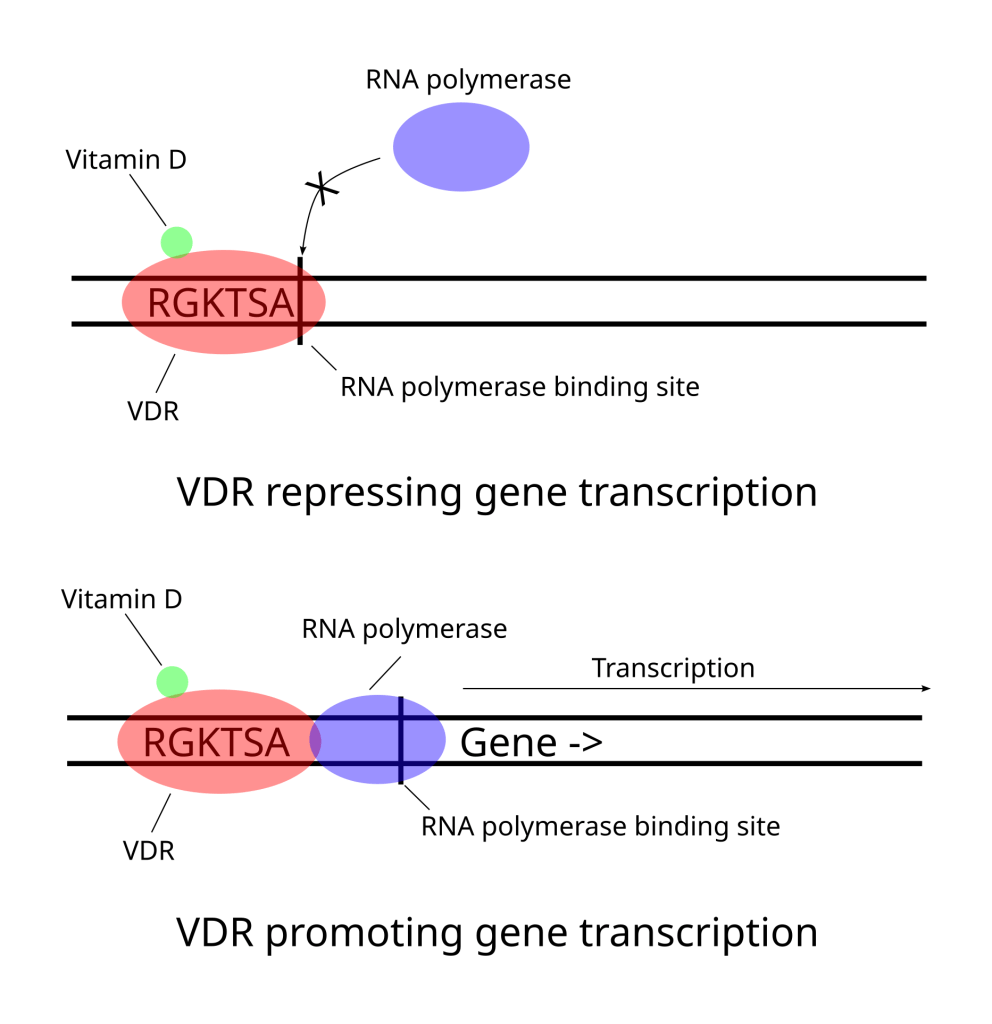

To understand why vitamin D deficiency can be a problem we need to have a quick look at some genetics. The central dogma of genetics is the idea that information encoded in our DNA is transcribed into RNA and then translated into proteins. Proteins are the primary agents of biological activity performing a wide variety of jobs in our bodies. They act as structural molecules, they catalyse important biochemical reactions and they serve as signalling molecules for cell-to-cell communication, among many, many other activities. All our proteins are encoded in our DNA but our development from an embryo to a grown human, and our continual good health, rely on a precise orchestration of gene expression to ensure that the correct proteins are available in the right place at the right time.

One of the ways this delicate balancing act is achieved is through transcription factors. Transcription factors are proteins that bind to sections of DNA adjacent to genes and either inhibit or promote the transcription of that gene into RNA. It is a way for the cell to turn specific genes (and thus their proteins) on or off. Vitamin D is a crucial part our metabolism because it is an essential co-factor of a transcription factor called vitamin D receptor (VDR)3. Once VDR is activated by vitamin D it promotes the expression of some genes and stops the expression of others. VDR influences processes as diverse as calcium and bone homeostasis, cell growth and differentiation, immune system regulation, circadian rhythms and DNA repair (if you want to get into the weeds see here). Without vitamin D enabling the function of VDR we are not able to produce the proteins we need when we need them.

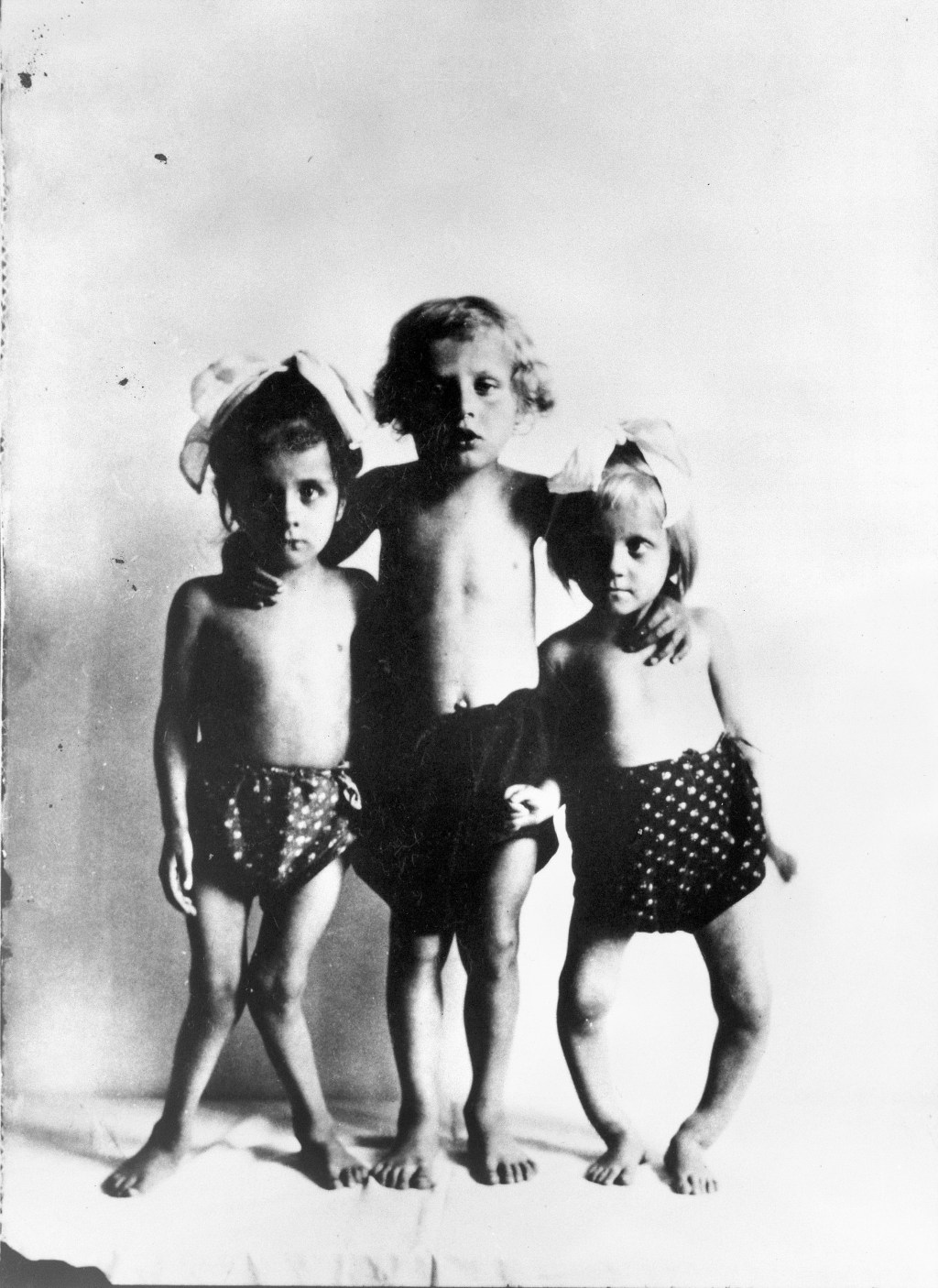

The most well-known consequence of vitamin D deficiency is rickets, a childhood disease that first rose to prominence in the urban ghettos of northern Europe during the early industrial revolution of the 1600s. Living in close set houses under the pall of pollution from industrial coal burning children could not get enough sunlight and rickets become a serious public health problem. Children with rickets cannot make strong enough bones and as they grow, and gain weight, their bones start to bend causing limb deformities, delayed growth, muscle weakness, and dental problems. By 1900 it was estimated that an amazing 80–90% of children living in Northern Europe and in Northeastern United States had suffered from rickets.

It took around 200 years before a connection between sunlight and rickets was made and it wasn’t until the early 1900s that the role of vitamin D in the development of rickets was established. Public health campaigns encouraged parents to get their kids in the sun but it was also realised that if you can’t get vitamin D from sunlight then you need to get it from your diet. So fortifying foods, particularly milk, with vitamin D became common. In fact adding vitamin D to food became something of an obsession with all manner of foods getting the vitamin D treatment, including custard, hot dogs and even beer. By the 1930’s the combination of public awareness of the importance of sunlight and the supplementation of many food stuffs with vitamin D led to the eradication of rickets.

There was a problem though. Long-term over use of vitamin D can lead to a condition called hypervitaminosis D one of the symptoms of which is hypercalcaemia, high blood concentrations of calcium in the blood. Hypercalcaemia can cause over-calcification of bones and soft tissues including arteries, heart and kidneys and, if left unchecked, can culminate in kidney failure and eventually death. In the 1950s several high profile cases of what appeared to be hypercalcaemia led to the banning of vitamin D supplementation in the UK, closely followed by the rest of Europe. Bans that are, for the most part, still in effect with some limited supplementation of milk allowed in a handful of countries. Ideally, given the high levels of vitamin D deficiency, it would seem that supplementation of basic food stuffs would be a good strategy. But the question health regulators wrestle with is what is the optimal daily intake of vitamin D?

The problem is that there is an assumption that one size of vitamin D supplementation can fit everyone in society, a common assumption when discussing dietary issues. But evidence is building that this is not a valid assumption. Firstly, it was likely that the cases of hypercalcaemia that led to the ban were actually a condition known as Williams syndrome, one of the symptoms of which is an extreme sensitivity to vitamin D. Williams syndrome is a relatively rare genetic condition and clearly those with Williams syndrome have a different vitamin D requirement than other members of society. But in recent years it has become clear that variations in vitamin D sensitivity are not limited to sufferers of Williams syndrome and sensitivity to vitamin D can vary significantly from one person to another. That is we may all have a personalised response to vitamin D.

As vitamin D is directly involved in the expression of genes there is ample scope for genetic variation in peoples response. Not only in the transcriptional machinery that vitamin D interacts with but also the genes that it regulates. And, though the molecular biology is poorly understood, several studies (here and here for example) have found that individuals can indeed be divided into low responders and high responders to vitamin D. Low responders need higher daily doses of vitamin D while high responders need less for a similar effect. This doesn’t appear to be a matter of people being more or less efficient at producing vitamin D. Rather it is at least partially attributable to the extent that vitamin D exerts it’s regulatory activity in an individual’s genetic context.

The ongoing debate about an optimal dosage of vitamin D is a sure sign that there is a lot more we need to work out. But vitamin D is a good case study in nutrigenomics because it directly affects the expression of a whole class of genes while displaying a sensitivity to the genetic variation found in an individual. To my mind vitamin D has shifted from being a dietary component to displaying characteristics of a drug. Drugs like warfarin display differential sensitivity, that are at least partially attributable to genetics, very much similar to what I have just described for vitamin D. The question now is what other parts of our diet have a significant genetic component that mediates an individuals response to those compounds? And that question should keep scientists busy for some time to come.

Footnotes

- My apologies to identical twins, triplets etc. You are almost unique. ↩︎

- A steroid is characterised by a four ring structure and a secosteroid is one in which one of those rings has been broken open. ↩︎

- More accurately, vitamin D3 is first metabolised to a form called 1,25(OH)2D3, also called calcitriol, which is the actual co-factor of VDR. Although a very important distinction for regulation of vitamin D production, for our purposes, we can ignore this detail. ↩︎

Leave a comment