I love mushrooms. I love them in gravy, I love them roasted, I love them in stir fries and I love them sauteed on toast. I like cheap ones and I like fancy ones. Hell I can’t slice a bag of button mushrooms without eating half of them raw. Mushrooms are great but, thanks to some undergraduate botany courses, I also have an appreciation of just how really weird they are. Fungi are not plants, they are not bacteria and they are not animals, they are their own thing. They make up their own entire kingdom of living organisms. Genetically fungi are more similar to animals than plants. Like animals they do not photosynthesise and get their nutrition by digesting and absorbing organic matter. But, unlike animals, they can’t move about and they are as rooted in their place as plants are in theirs. Remarkably, for an organism that seems so simple, they may have short-term memory and the capability for decision making, enough evidence existing for which that some scientists are starting to talk about a ‘fungal mind’1.

The most cursory internet search brings up dozens of interesting facts about fungi. The largest organism on earth is a fungus covering 3.4 square miles in Oregon and it has existed for at least 2,500 years. Fungi are crucially important to the breakdown and decomposition of organic matter and the recycling of nutrients for animals and plants. Fungi can be parasites and can infect some species of insect, especially ants, and turn them into a zombie army dedicated to ensuring the survival and reproduction of the fungi. Yes, The Last of Us is a documentary if you are an ant. Fungi have been important to humans for thousands of years, Otzi the Iceman had two types of fungi in his pocket that he was probably using as some type of medicinal product. And, of course, they have always been a source of food, but don’t eat the wrong mushroom or you’ll die a painful death. Just ask the Roman emperor Claudius who was poisoned by his wife Agrippina using mushrooms, clearing the way for her son Nero to become emperor.

You could write a thousand blog posts on fungi but this is a food blog so I want to focus on fungi as food. When we talk about edible fungi we tend to think of mushrooms, so lets look at them first, but keep in mind that yeasts and molds are also fungi and I’ll get to them later in the post. All fungi that aren’t yeast are made up of fine, branching thread-like structures, called hyphae, that form a matted mass or network called a mycelium. What we think of as mushrooms are actually ephemeral structures, called fruiting bodies by biologists, that are formed by the mycelium to produce and disperse spores that will ultimately grow into new mycelial networks. It is the mycelium that is the permanent embodiment of a fungus and it can be microscopic or span acres, like in Oregon. To feed itself the mycelium secretes digestive enzymes that break down organic matter in it’s immediate environment into smaller molecules that can be easily absorbed as nutrients.

There are about 1000 species of edible fungi and in most cases we only eat the mushrooms of the fungus (which provides a certain perspective when you recognise that we are eating the reproductive organs of a filamentous organism that decomposes anything it comes in contact with). We can divide edible fungi into three broad groups based on how they go about obtaining their nutrients. Some fungi grow on decomposing plant material, either dead vegetation or the dung of plant eating animals, and this group includes well known mushrooms like button and shiitake mushrooms. Some fungi parasitise other organisms and those of dietary importance tend to parasitise plants, like, as we’ll see later, Ustilago maydis in corn. Finally, some fungi can form a symbiotic relationship with a plant that benefits both organisms. Truffles or chanterelles, for example, are the fruiting bodies of fungi that share nutrients they gather from the soil in exchange for sugars produced by the trees they are growing on.

The way that a fungus makes it’s living, so to speak, has ramifications for our ability to grow that fungus for food. Button mushrooms, for example, are relatively easy to grow, you just need to give them something to grow on, some manure, for example, and they’ll be happy. On the other hand something like a truffle is very difficult to cultivate as it requires specific trees to grow on and it is very picky about the soil and climate. It can take many years before cultivated truffles can be harvested and even then yields are uncertain. Because of this mushrooms like truffles, chanterelles and morels are still mostly wild-harvested rather than cultivated and this is why they can be so expensive.

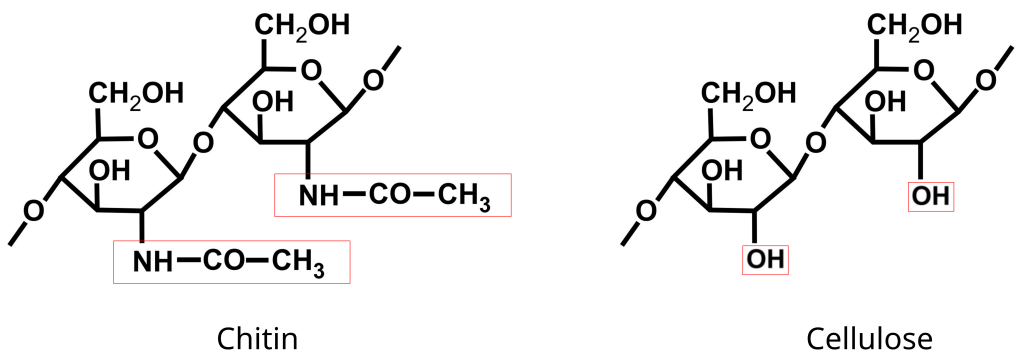

In previous posts I’ve talked a lot about the chemistry of plant and animal cells but, as I’ve tried to point out, fungi are different and so almost none of that is useful to us now. Fungi are genetically more similar to animals but they still have cell walls, like a plant, but instead of being made of cellulose, like plant cell walls, fungal cell walls are made from chitin, which is what insects use to make their exoskeletons. Chitin, like cellulose, is a polysaccharide but while cellulose is made up of glucose monomers chitin is made up of 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-glucose. Which in English means a glucose molecule with one OH group replaced by an acetyl amine group. OK, that’s not much better English but what it means is that chitin is able to form more hydrogen bonds which makes structures made of chitin stronger, or harder, than those made of cellulose. If you mentally compare the shell of an insect to, say, a stick of wilted celery you can conceptualise how much harder chitin is than the cellulose2.

Apart from chitin, the fungal cell wall is also made up of glucans, polymers of glucose, other unique polysaccharides and a class of protein called mannoproteins. These mannoproteins are proteins that also contain 15-90% mannose, a simple sugar similar to glucose. These glycoproteins are important for wine making as yeast, a fungi remember, releases mannoproteins when they die. So wines that are aged on the lees, the bodies of dead yeast cells, benefit from the release of these proteins which can improve wine in a number of ways. The mannoproteins enhance some aromas and flavours, prevent the crystallisation of potassium bitartrate and prevent cloudiness from protein haze, a problem in white wines where denatured proteins make the wine go cloudy. The mannoproteins are able to stabilise these proteins and prevent them from denaturing.

Another way of classifying fungi is by whether they have gills or not. The classic mushroom shape is a stalk with a cap that contains the thin, wavy gills. In these fungi, the gills are where the spores get released and are hopefully, from the mushrooms perspective, dispersed somewhere suitable to become new myceliums. The gills increase the surface area available for this process and they are also usually positioned to facilitate dispersal of the spores by the wind. Mushrooms with gills include matsutake, shiitake and the common button mushrooms. Mushrooms without gills have pores which release the spores and this group includes morels, truffles and chanterelles. This group also includes the oddly but aptly named ‘Chicken of the Woods’ which tastes like chicken and can be used as a chicken substitute.

Whatever their shape all mushrooms are basically water and air held within a chitinous framework. This means you need to keep a couple of things in mind when you cook them. Firstly, mushrooms have an extensive system of ‘pipes’ that allow spores produced in the interior of the mushroom access to the surface for dispersal. Because of this network mushrooms are effectively sponges and, when fresh, they will absorb any fluid they come into contact with. If you start cooking mushrooms by putting them in a pan with oil they will absorb a lot of that oil before they are cooked. Secondly, mushrooms are 90-95% water, this is a lot of water and when they get hot enough they will release all this water into your dish potentially making it soggy.

So, when cooking mushrooms you want to start them off on a dry heat, or maybe with a little bit of water, so they don’t absorb any oil or fat. Then you want to get them hot enough to release their water and only when this water has evaporated add some oil or butter. By the time the water has evaporated some of the internal structure of the mushroom will have collapsed and they will absorb less of your cooking fat. As a general rule, high heat is the way to go with mushrooms, stir frying for example, as the lower the heat the longer they will stew in water, preventing Maillard reactions. If they are going into a stew or something that will have a lot of liquid anyway this is not so important, but you might want to take into account the water released by the mushrooms when adding a liquid.

Mushrooms are also pretty forgiving in that they are almost impossible to overcook. As I mentioned above, chitin has an enhanced hydrogen bonding capacity which means a chitin molecule can bind tightly to other chitin molecules and this increases its ability to withstand high temperatures. In fact chitin is stable up to about 300C (572F), a temperature you’ll probably only ever reach if stir frying and which you’ll never reach if braising or roasting. So mushrooms will retain their shape and texture in a wide variety of dishes no matter how long, within reason, you cook them. In comparison, cellulose is stable up to around 260C (500F) so all the plant matter in a dish will have turned to mush long before the mushrooms start to degenerate.

In terms of flavour, everyone knows that mushrooms bring plenty of umami to a dish and this is because they contain a large amount of free amino acids, in particular glutamic acid which is one of the primary ingredients of MSG. Mushrooms are also rich in molecules that can synergistically enhance the taste of MSG. At least two molecules, guanine monophosphate (GMP) and inosine monophosphate (IMP), are thought to target the same receptors as MSG and are able to amplify the umami taste caused by MSG. Shiitake mushrooms, well known umami bombs, have a particular abundance of GMP, so much so that the discovery of GMP as a MSG enhancer was made in this species of fungus.

Apart from umami flavours different species of fungus can differ radically in flavour. I’ve already mentioned the chicken-like flavour of the ‘Chicken of the Woods’ mushroom but this is just one component of the mushroom flavour rainbow. Other examples include porcini mushrooms, that provide a slightly sweet and nutty flavour, Lion’s mane mushrooms, that mimic the flavour of crab or lobster and can be used as a seafood alternative, and beech mushrooms, that bring a nutty note to a dish. Unfortunately, I have neither the knowledge or the space to describe all the flavours of the different types of mushrooms but at least one research group has attempted to define a lexicon of mushroom flavours and it is here if you want to explore further.

Mushrooms are also well stocked with molecules that contribute to an attractive aroma. When damaged mushrooms produce octenol from polyunsaturated fats which contributes to the typical aroma of fresh mushrooms. Octenol is produced mainly in the gill segments so the more mature a mushroom, and the more open the cap, the greater the amount of octenol it can produce. In the wild it is thought that octenol is produced by mushrooms to deter attack from snails and some insects. Octenol is also a component of human breath and sweat, which, for someone who likes the smell of mushrooms, has some disquieting consequences that I would prefer not to think about. But because octenol is a characteristic human odour it is a powerful attractant for mosquitoes and is often used in mosquito traps.

Similarly, the distinct aroma of shiitake mushrooms is caused by a molecule called lenthionine, a cyclic oligosulfide, that contains large amounts of sulfur. Lenthionine gives shiitake mushrooms, and garlic and onions where it is also found though in lesser abundance, a sulfurous or earthy aroma. Sulfur is an important element in human flavour and aroma detection. In it’s pure form sulfur is odourless but when combined into sulfur compounds it contributes to a variety of aromas detectable by humans. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), for example, has an aroma that anyone who has smelt a rotten egg would immediately recognise. Less offensive aromas are created when sulfur is incorporated into different molecules and these contribute to the aroma and flavour of many foods. Thiols, a sulfur analogue of an alcohol, are important in wine making, there are a bunch of sulfur containing compounds in hops and beer and the flavour of truffles is due to sulfur containing compounds like dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl disulfide.

Even after harvest mushrooms are metabolically active and a lot of the flavour and aroma molecules can be produced by enzymatic activity long after the mushrooms have been picked. For this reason the flavour of just about all mushrooms will intensify if they are dried before cooking. If cooked fresh and at high heat, the enzymes that produce the flavour molecules don’t have time to produce a large amount of the flavour molecules. But when slowly dried more flavour molecules will be produced as enzymatic activity is retained over a longer period of time. The drying process also results in Maillard reactions and the evaporation of water acts to concentrate the flavour. Drying mushrooms is not only a convenient way to preserve and transport mushrooms but also a very effective way to enhance their flavour.

Finally, I want to wrap up with a quick word about molds. Molds are not things that we associate with food, usually they are something you are trying to clean off your bathroom tiles. But they are fungi and there are some interesting cases where we have found a way of making them into food. My favourite, because it makes a delicious wine, food-related mold is Botrytis cinerea. This fungi is usually a pest that infects and forms a grey mold over many fruits and vegetables. But, if used in a controlled way during wine production, the water loss from the grapes caused by the infection concentrates the sugars in the grapes. When used to make wine these grapes will produce a very sweet wine but one that is also quite acidic, which contributes a zest to the wine that balances out the sweetness. Sauternes, from France, are the classic example of a botrytis wine, though Trockenbeerenauslese, from Germany and Austria, and Tokaji Aszú, from Hungary, are other examples. The importance of Botrytis for the production of these wines is summed up in the name given to the infection: ‘la pourriture noble’, the noble rot.

Although Botrytis is important for the wine production process we don’t actually consume the mold itself. But there are some examples of edible molds. Huitlacoche, also known as corn smut, is caused by a mold, Ustilago maydis, that infects corn. The infection causes the kernels to swell up into a structure known as a ‘gall’ which is a combination of swollen plant cells, the hyphae of the mold and a bunch of blue-black spores. When cooked the galls have the consistency of a mushroom and a sweet, smoky flavour. It is a delicacy in Mexico where can be incorporated into almost any dish, often as a meat substitute, and has been eaten since Aztec times. A fungus from the same genus, Ustilago esculenta, does something similar to an Asian wild rice species, Zizania latifolia, where it forms galls in the stem. These galls can be harvested and are a delicacy in China, Japan and other parts of Asia. I haven’t had the opportunity to taste this mold but apparently it tastes somewhat like bamboo (according to Harold McGee).

There is so much more to the fungi world, their sex life is particularly fascinating, but I’ve gone on for too long yet again. I hope I have inspired some enthusiasm for fungi in general and as ingredients in our food. I want to finish up with a warning though. Here in Australia the courts are dealing with a murder of three people by someone using wild-picked mushrooms and this is a good reminder of just how deadly some of these mushrooms can be. Fungi really don’t want things eating their reproductive organs, mushrooms are for producing more fungi not for flavouring our pasta dishes. For this reason mushrooms produce a whole bunch of molecules that are designed to stop other organisms from eating them. That some of these molecules make them tasty to humans is just an unfortunate accident from an edible fungus’s perspective. But a lot of mushrooms are not edible and are actually quite effective at deterring mammals from eating them and, in humans, they can cause serious illness or death.

So unless you really, really know what you are doing don’t go mushroom picking yourself. Mushrooms come in all shapes and sizes but some deadly species look a lot like edible species. Agaricus xanthodermus is one mushroom that causes a lot of poisoning cases because it resembles other, edible, mushrooms, and there are more like this. So leave the mushroom gathering to experts and enjoy the fungi available at your local market that, unfortunately for them, aren’t quite so good at stopping us eating them.

Footnotes

- Somewhat controversially it must be said. See here for a scientific review and here for a lay description of this issue if you want to make up your own mind ↩︎

- Chitin is also the primary material of crustacean shells, crabs and prawns, for example. Though in this case chitin is combined with calcium carbonate to make an even harder exoskeleton. ↩︎

Leave a comment