Most of us have now heard of umami and we probably all know that umami is now recognised as the fifth of our primary tastes, formerly limited to sweet, sour, bitter and salty. You might also know that Western societies were a bit slow to the umami party. Despite being recognised in the East for many years it was really only in the early 2000s that umami was truly accepted as the fifth taste in the West. I am old enough to remember when umami first started penetrating the Western zeitgeist and it seemed odd to me. It was like scientists had uncovered the fact that we had an extra arm, or a tail, that we had never noticed. How could something so fundamental to the human experience as a whole taste have gone unnoticed all this time? The answer, of course, is that we had always had umami we just called it savoury. Umami, or savoury, flavours are in a heap of western foodstuffs: meat, tomato, mushrooms, anchovies, cheese, cured meats, peas and corns, amongst many other sources, all add umami flavours to a dish. Being Australian, Worcestershire Sauce was liberally used in our household as well as the kids perennial favourite, tomato sauce, both sources of umami.

Despite the many sources of umami, the idea of savouriness as a flavour all it’s own never really arose in the West. The word savoury denoted a kind or richness or meaty quality of savoury food but it was never really thought of as a distinct flavour. I’m speculating but in Western cuisine most of the foods that contributed umami to a dish had a distinct flavour profile of there own. Unlike sugar and salt that are unambiguously sweet or salty and, slightly less so, for things like vinegar or yoghurt, for sour, and kale, brussels sprouts or dark chocolate, for bitter. It was easy to add too much salt or too much sugar to a dish but savoury was a much more subtle thing and without any real source of ‘pure’ umami it was a little hard to over-umami a dish. If you add too much meat or too much tomato the dish just ends up tasting like meat or tomato. To over-umami a Western dish, you’d probably need to add too much parmesan, Worcestershire sauce or anchovies and that is a little harder to do than just adding too much salt or lemon juice.

In the East, however, the situation was slightly different. The Eastern diet has plenty of traditional sources of almost ‘pure’ umami. Fish sauce, Soy sauce, miso, shrimp paste, kimchi and even shitaake mushrooms are all umami bombs that are used liberally in Asian cooking precisely because of the umami flavour that they impart to a dish. Miso soup, combining miso paste and dashi for example, is almost pure umami. I’m still speculating, but I think it is fair to say that umami was something that Asian people were a lot more comfortable with. Also, thanks to the intensely umami ingredients available, it was probably a lot easier to over-umami an Asian dish than one using typically Western ingredients and this forced cooks to account for umami as a distinct taste in the flavour profile of a dish. The increased familiarity with umami by both cooks and consumers probably made it inevitable that someone in Asia would start thinking about umami as a taste right up there alongside sweet, sour, bitter and salty.

In fact the ‘discovery’ of umami occurred precisely this way; the search for umami was initiated by a Japanese chemist wondering if there was an umami flavour after eating dashi. The story goes that in 1908 a Japanese chemist, Kikunae Ikeda, noticed that his wife’s kombu dashi, a dashi made from a type of edible kelp or seaweed, had a flavour that he couldn’t really classify as sweet, salty, sour or bitter. So he boiled down 90 pounds of kelp and started isolating molecules from the resulting sludge and tasting them (chemists often used to experiment on themselves back in the day which made for some fun stories in the field of pharmacology). What he ended up with was a few grams of a brown crystalline substance that tasted of umami.

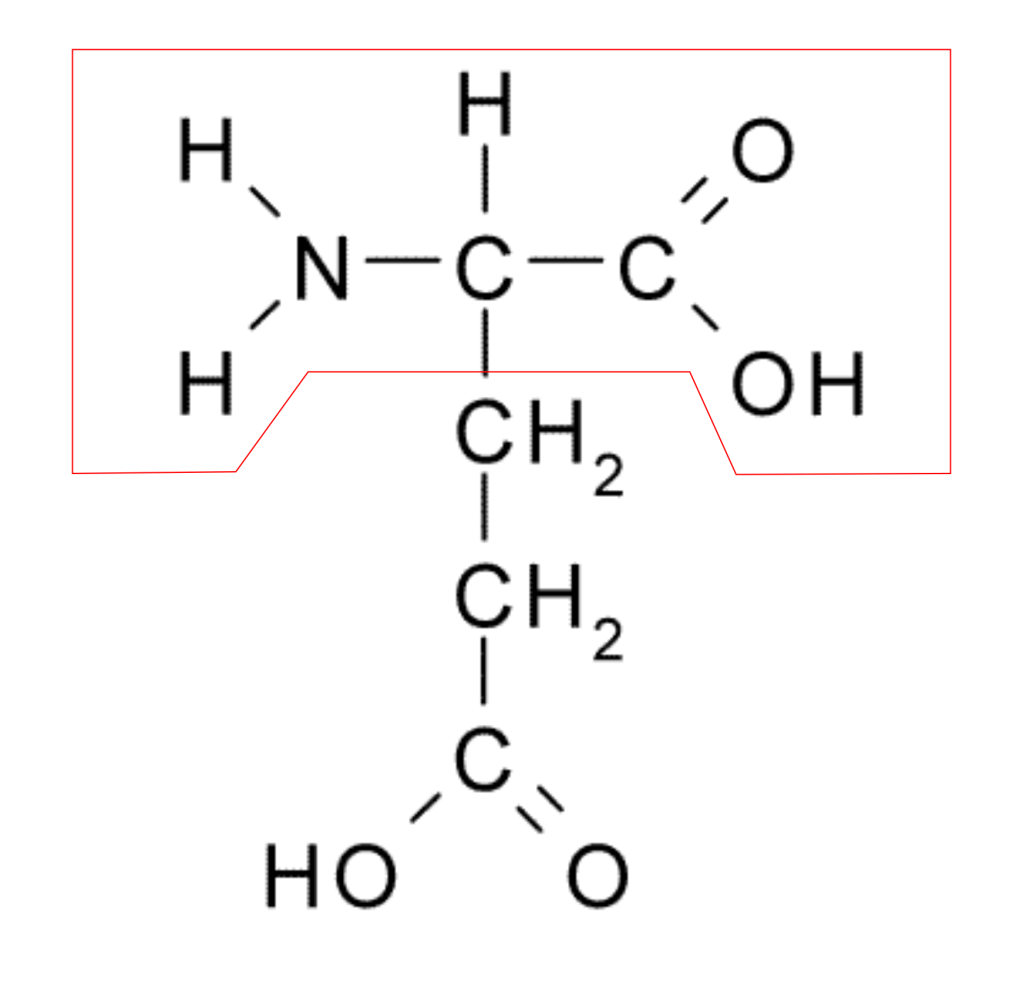

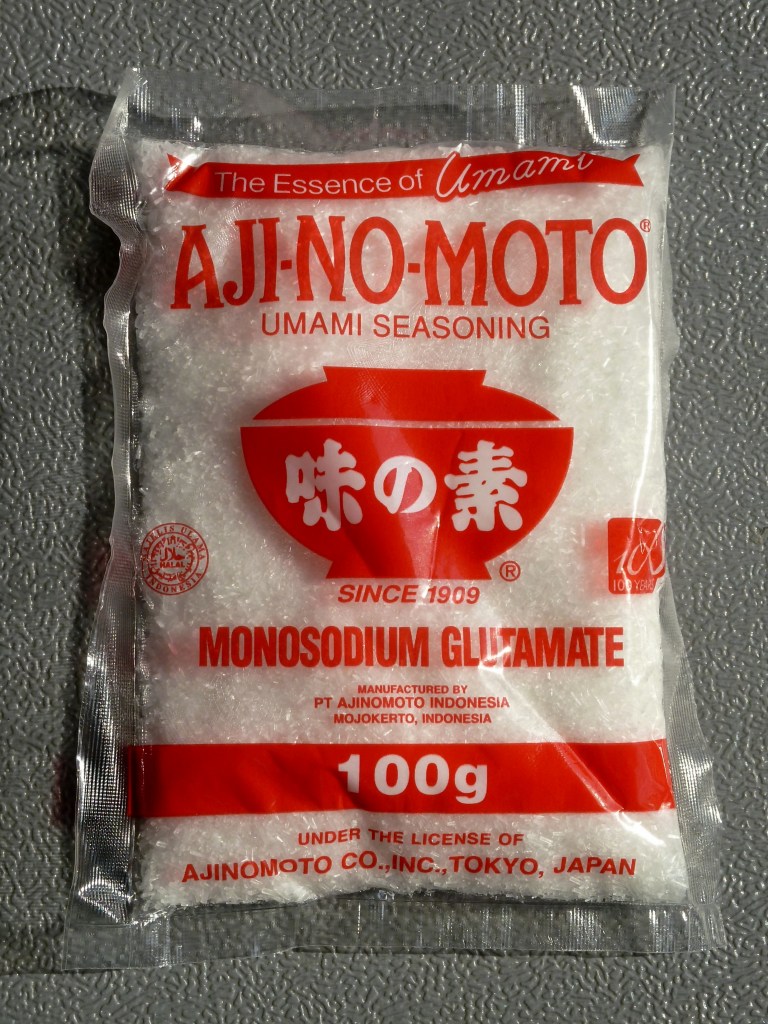

This substance ended up being glutamate, or glutamic acid, a substance that we have seen before as it is an amino acid, one of the building blocks of proteins. Kikunae developed a commercial version of glutamic acid and called it ‘Aji-no-moto’, or Essence of Flavour, and the company he created, Ajinomoto, went on to become one of Asia’s bigger food companies. It took a while for Kikunae’s work to get to the West but by the 1930’s and 40’s, with the rise in popularity of Chinese food, westerners started becoming aware of ‘Aji-no-moto’ although we gave it a much more prosaic name: monosodium glutamate, or MSG.

The typical MSG narrative now normally goes on to talk about how the West, well the US mainly but I do remember MSG fear in Australia as well, was somewhat reluctant to accept this new, exotic flavour enhancer from the East. The creation of a ‘Chinese restaurant syndrome’ from a single two paragraph letter to the New England Journal of Medicine in 1968 and the consequent fear and panic over MSG, fuelled by stereotypical conceptions of Eastern culture (yeah I’m trying to say racism nicely). But all this has been covered elsewhere (here, here and here). There is also an angle that I might revisit in a future post about some spectacularly bad science that backed some of these early ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’ claims. What I do want to do here is to look at some of the science behind taste and how we experience flavour. I still think the ‘discovery’ of umami as a new taste was pretty cool and, believe it or not, umami may not be the end of the story as there maybe a few more potential new ‘tastes’ on the horizon.

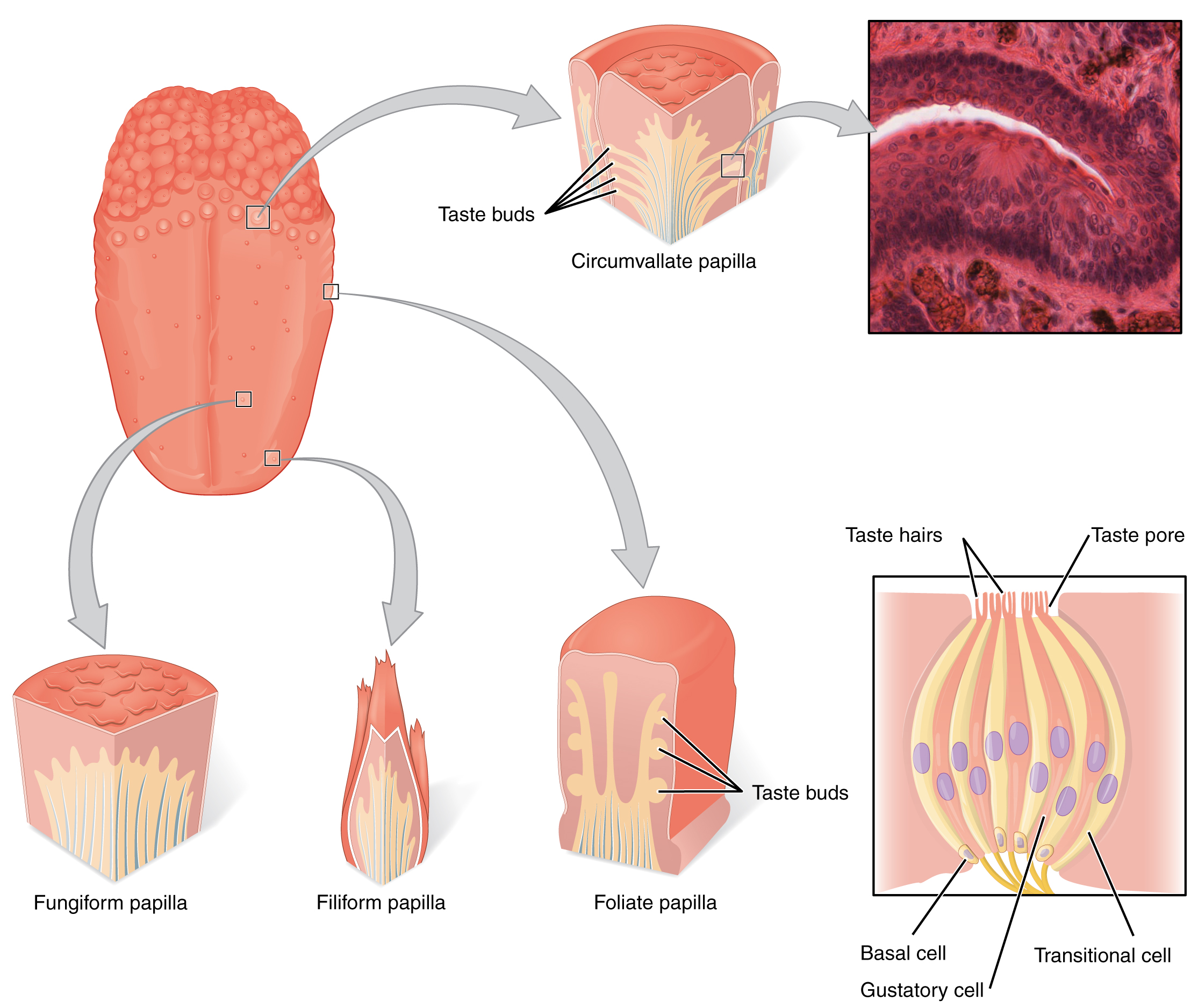

The way that humans perceive taste is incredibly complex and in some respects it is very poorly understood. But at the most basic level, taste is the interaction of molecules in our food with taste receptors on our tongue, palate and throat. These taste receptors are on the surface of cells within structures known as taste buds, which are, in turn, grouped together within structures known as papillae. Papillae are the little bumps you can feel on your tongue and they are also found on the cheeks, palate, throat and epiglottis. When we eat, food molecules are dissolved in our saliva and they enter the papillae via a ‘taste pore’. In the papillae food molecules then come into contact with the receptors on the taste buds which triggers a cascade of intracellular events that, ultimately, results in nerve impulses that are used by our brains to construct the sensation of taste.

This concept of food molecules interacting with receptors on the surface of cells is not completely foreign as we’ve covered it before when looking at chillies. In that post we learnt that capsaicin molecules activate TRPV1 heat receptors that signal a burning sensation to the brain via nerve impulses. But the TRPV1 capsaicin receptor isn’t classified as a taste receptor because what makes a receptor a taste receptor is that it can be found in a taste bud. This doesn’t mean taste receptors can’t be found outside taste buds, for example they can be found expressed on cells in the early parts of the GI tract, and some taste receptors have also been found in the lungs. So a general rule of thumb is that a receptor is a taste receptor if it is found in a taste bud, even if it can occur elsewhere.

Each taste buds has multiple different types of taste receptors and can detect multiple different types of tastes and every part of your tongue can detect all tastes. Previously it was thought that the tongue was divided up into a sweet zone, a bitter zone and so on. You might even have seen diagrams of the tongue divided up into zones corresponding to the four different tastes but you should forget that idea right now. It’s old news. Each taste bud has all full complement of taste receptors though the number and ratios between each type of receptor may vary between taste buds.

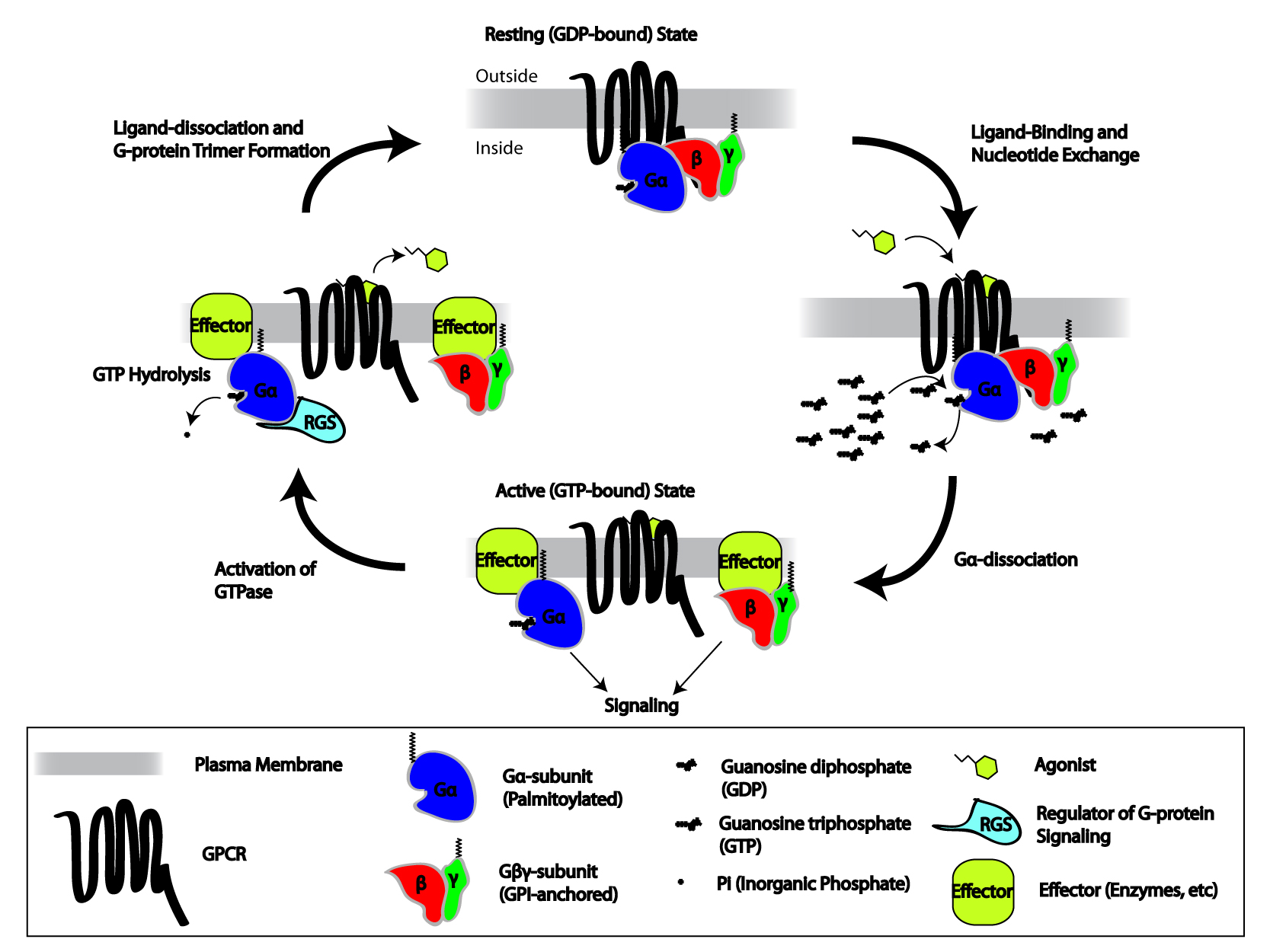

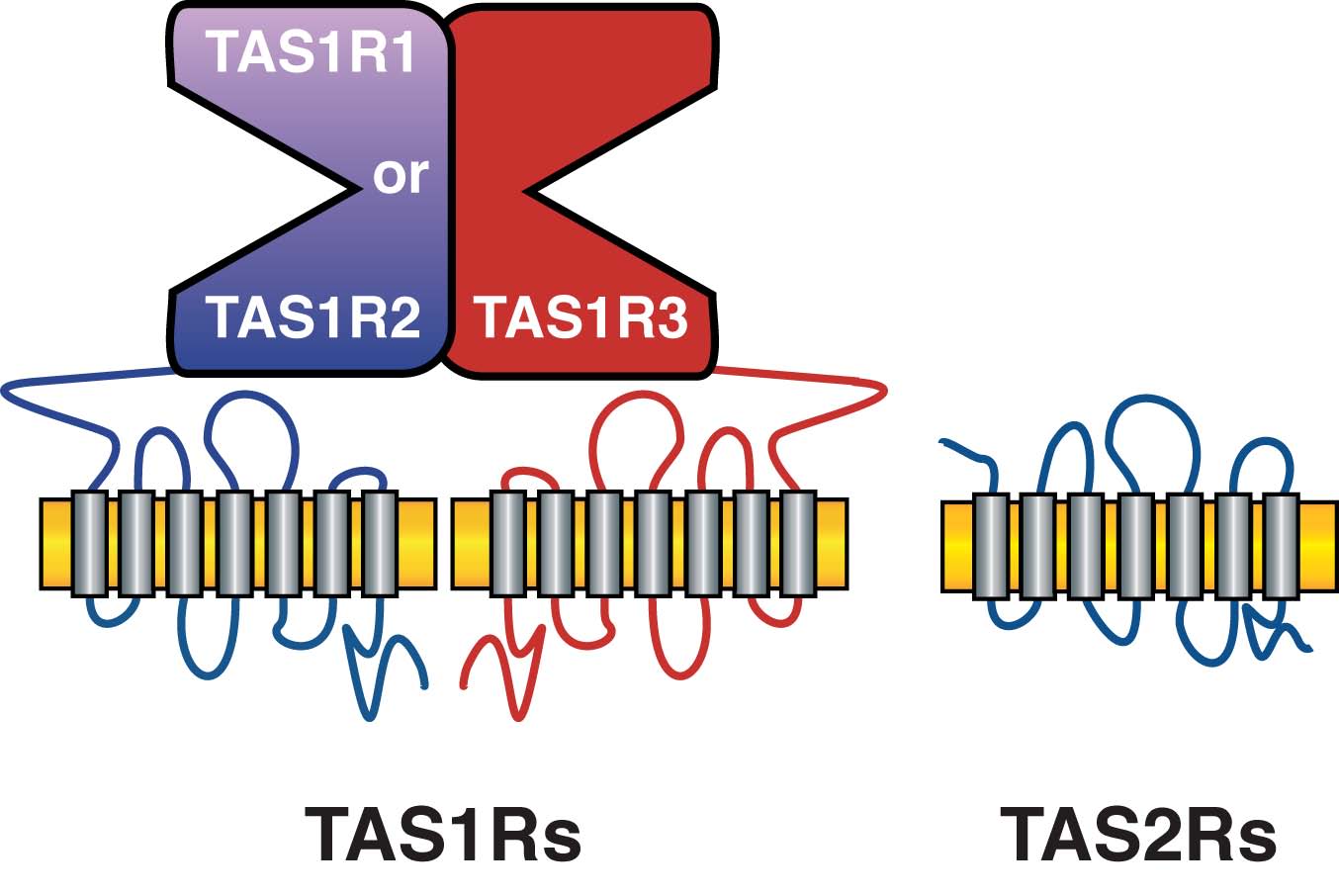

Receptors for sweet and bitter are the best characterised though, surprisingly, even these receptors were only characterised at the turn of the century. There are three sweet receptors (the TAS1R genes) and a massive 25 bitter receptors (the TAS2R genes). The receptors encoded for by these genes are all G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). We haven’t come across GCPRs before, the capsaicin detecting TRPV1 capsacian receptor is an ion channel receptor, but a GPCR spans the cell membrane and has a part of the protein outside the cell membrane and a part of the protein within the cell. The internal part of the protein is able to interact and activate with a specialised protein, called a G-protein, when a molecule binds to the receptor on the outside part of the protein. This triggers a pathway, often called a transduction pathway, that results in some cellular effect. In the taste receptors it results in the release of neurotransmitters by the cell that trigger a nerve impulse that shoots off to the brain.

To make one sweet taste receptor you need two TAS1R proteins working in concert, specifically TAS1R2 and TAS1R3, and they can bind a whole bunch of sugars and sugar substitutes. To make a umami receptor you also need two TAS1R proteins working in tandem, but in this case it is TAS1R1 and TAS1R3. This complex of two proteins is able to bind amino acids, especially glutamic acid. Bitter receptors don’t need to form a complex to act as bitter receptors but the proliferation of bitter taste sensors highlights the evolutionary importance of being able to detect bitterness. Many poisons and toxins, especially plant toxins, are bitter. So as omnivores, who eat both meat and plants, being able to detect a wide range of bitterness is a good way to protect ourselves from harmful food stuffs. Carnivores could be expected to have fewer TAS2R genes because they don’t eat a lot of plants and sure enough cats, for example, have only three full copies of the TAS2R genes (see here for more on the evolution of bitter taste receptors).

We’ve only really begun to explore the mechanisms of taste perception and the roles of all these different genes, but I’m willing to bet that genetic variation in TAS2R genes, and other taste receptors, can explain differences in the perception and preferences for different types of food by different people. It is also interesting that TAS2R bitter receptors are also expressed throughout our airways and gut. Bacterial, and even parasitic molecules, can activate these receptors triggering an immune response against pathogens. Our immune system is often called our sixth sense because it is able to ‘sense’ pathogens in our environment and react accordingly. So, in a weird way, it makes sense that sensory receptors could also be used in this capacity, we ‘taste’ the bacteria that threaten our well being.

The other tastes, sour and salty, also appear to be receptor mediated with a variety of ion channel receptors identified as actual receptors or potential receptors, though they are not as well characterised as the sweet/bitter/umami receptors. Interestingly we may not be done with other flavours either, a ‘fat’ receptor has been proposed, called CD36, a carbonation receptor (which has been identified as an enzyme attached to the sour receptor) as well as alkaline (the opposite of sour), metallic, watery and ammonia chloride (think spoiled fish or meat) receptors all being proposed as a way of providing new tastes (see here for more on this).

This proliferation of potential taste receptors makes sense, the whole reason that we have a taste system, called a gustatory system by scientists, is so we can identify what is in our food. We need this to not only avoid substances that may harm us but also to identify foods that are a good source of specific nutrients. Our gustatory system has evolved to allow us to work out what is in food by it’s taste, carbohydrates are sweet, proteins are umami and bitter things are potentially toxic and so on. Picking on cats again, cats cannot taste sweetness and this is because they are carnivores and have no need to know if they are eating something that is high in carbohydrates so they have lost the capacity to sense sweetness over the course of evolution (see here for an easy read on the evolution of taste in various animals). So it makes sense that we could have a taste that alerts us to spoiled meat and a ‘fat’ sensor that lets us detect fatty acids in a potential food source; in the modern world though maybe we should disconnect them so we can resist Big Macs when we are hungry?

I should probably mention one more thing. The gustatory system isn’t my field, neither is neurobiology, so after reading about taste receptors I was a little confused. Given that a receptor will interact with a food molecule and shoot off an impulse to the brain how can the brain decipher which tastes are being triggered by what receptors? Can a single nerve fibre signal more than one taste or do you need multiple nerve fibres signalling specific tastes? Turns out no one actually knows yet, though there are two competing models. The “labelled line” model requires distinct neuronal pathways for each taste while the “across-fibre” model allows for a combinatorial approach by the brain which is able to detect patterns of flavour across multiple neuronal inputs. To say that this is complicated stuff and way beyond the scope of this post is an understatement but if you want to go deep this here is a pretty good review and starting point (that I’ll be using for future posts as well).

I haven’t really done justice to this complex topic but it is a good starting point for later posts. I’ve really only talked about our taste buds but they are only a small part of what we experience as taste. Anyone who has lost their sense of taste when they have a cold knows that the olfactory system plays a huge role in flavour. And sight and even hearing may play a role in how we experience the flavour of dish, Heston Blumenthal for instance used to serve a seafood dish with headphones and any wine lovers know that a wine tastes better at the cellar door than when you get the case back home.

Leave a reply to Are Michelin Stars All in Our Mind? – The Science of Food Cancel reply