I’m no historian but I think it would be fair to say that for most of history most humans relied primarily on starchy grains and vegetables to keep themselves and their families fed. Grasses like wheat, rice, oats and barley are easy to grow and the seeds, or grains, of these grasses are rich in carbohydrates making them a reasonably cheap way of obtaining large amounts of calories. But before we could unlock this bounty there was a problem. Plants store carbohydrates in grains as starch and humans cannot digest starch in it’s raw form. Cows and other ruminants have multiple stomachs, and some helpful intestinal bacteria, to digest starch. But humans, lacking this intestinal framework, needed to find a way to break down starch into a digestible form. So, as the masters of fire, we learned how to cook our starch and by doing so we set free the digestible sugars trapped in it’s crystalline structure. But there was a bonus, we also learned that something magical happens when you cook starch in the presence of water, something that we now call gelatinisation.

Because of gelatinisation not only does cooking break down the starch and make it digestible, but gelatinisation improves the texture of starchy foods, making them more pleasurable to eat. This is great if the majority of your diet is made up of grains and vegetables. Flour, for example, can be transformed from a dry indigestible powder into pasta which, when it is cooked in water, gets it’s soft yet pliable texture via the gelatinisation of starch. Gelatinisation also turned out to be a very useful tool in preparing a wide variety of other dishes. As gelatinised starch also increases the viscosity of fluids it became an indispensable tool for thickening sauces, soups, stews, puddings and other food stuffs while increasing the nutritional value of the meal. In the modern world starch, and the science behind gelatinisation, is still essential for a whole range of foods that we can consume on a daily basis. A sobering thought is that without starch and gelatinisation there would be no such thing as a French fry.

To understand gelatinisation we need to understand the structure and composition of starch. Starch is a complex polysaccharide (see here for refresher on sugars and carbohydrates if you need it) that plants use for storing energy. Plants, being unique in their ability to convert sunlight into chemical energy, produce starch when photosynthesis produces more glucose than is needed for their current energy requirements. Starch can then be broken back down into glucose to drive metabolism when energy is in shorter supply, at night time for instance.

Starch will also be stored by plants as an energy reserve for developing offspring. Potatoes, for example, have a lot of starch because they are the main means of vegetative reproduction (a form of plant asexual reproduction) for the potato plant. New potato plants develop from the ‘eyes’ of the potatoes and use the starch in the potato as an energy source until they are able to start photosynthesising themselves. Similarly, wheat and other grains have a high starch content to provide energy to budding offspring when the seeds germinate.

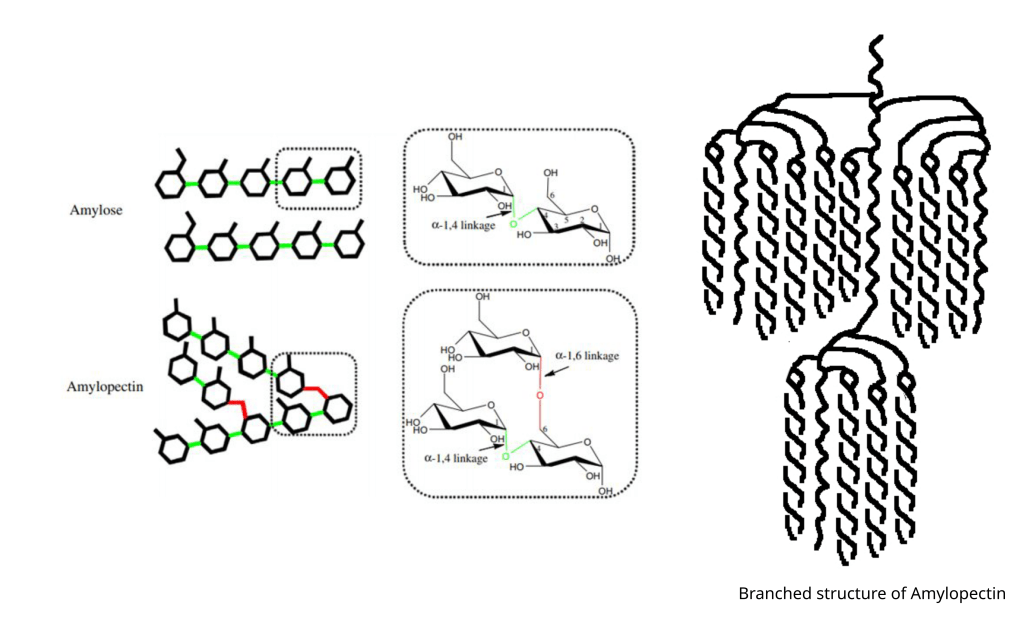

Starch is actually a mixture of two different types of carbohydrate: amylopectin and amylose. Amylose is a straight chain polysaccharide made up of between 500 and 5,000 glucose molecules linked together by glycosidic bonds (in the business known as alpha-1,4-glycosidic bonds). Amylopectin is also a polysaccharide made up of glucose molecules but, unlike amylose, the glucose molecules are occasionally bound by an alpha-1,6-glycosidic bond which gives amylopectin a branched structure. Amylopectin can contain between 500 and 20,000 glucose units with a branch occurring every 25-30 units which makes it a large and complicated molecule. Natural starches typically consist of 10-30% amylose and 70-90% amylopectin. Though some cultivated plant varieties can have starches composed of almost 100% amylopectin. Glutinous rice, for example, that is used to make Thai sticky rice has a starch almost completely made from amylopectin.

In plant cells starch is made and stored in specialised cellular compartments called amyloplasts and in the amyloplast starch is stored as insoluble particles called starch granules. The structure of these starch granules is quite complex, but simply put crystallised amylopectin forms layers interspersed with less order regions composed of amylose and the some of the branches of amylopectin (if you want to look into this further you can start here). The starch granule is what we need to be thinking about when we are using starch in our cooking because gelatinisation is the process of breaking down the starch granule into a matrix of carbohydrates that thicken and stabilise our food.

The starch granule is a pretty robust structure, in the plant there are a bunch of enzymes that are needed to break it down before the individual glucose molecules can be metabolised but in cooking we generally break it down using heat. Just like in water, carbohydrates can be held together by hydrogen bonds between partially charged hydrogens and another partially charged atom (usually an oxygen). At normal temperatures the amylose and amylopectin in a starch granule are held tightly together by hydrogen bonds between the chains. But when you start heating a granule the heat energy causes the carbohydrate chains to vibrate, hydrogen bonds can start breaking and the molecules move apart. In an aqueous environment water will take advantage of the extra space and start moving into the granule forming it’s own hydrogen bonds with the carbohydrates.

The influx of water causes the granule to start swelling and as they grow they increase the viscosity of the surrounding fluid. As heating continues the granule will grow even more and then amylose will start leaking from the granule. Finally after more heating the granule will burst apart as the amylopectin melts, releasing all the starch molecules. Once burst the amylopectin and amylose form a large complex that traps water and forms a gel (I’ve simplified a bit but if you want more details you can start here). There’s a good animation of the process below, from The Culinary Institute of America, that gives you a good idea of what I’m talking about (and also some spoilers for the rest of this post).

If all starch granules were created equally we’d only need one type of starch in the kitchen, but they are not. Starch granules from different species, or even different cultivars of the same species, can have different sizes, they can be made of different ratios of amylose to amylopectin and the amylose and amylopectin molecules can differ in size and branching complexity. This variety means that starch granules from different sources will have different properties and so will have different gelatinisation temperatures and produce different types of gels. A consequence of these differences is that different starches are better suited to different applications in the kitchen. We’ve already come across one example of this, the difference between the starch granules in waxy and starchy potatoes makes a big difference in the quality of a french fry.

One of the ways in which starches differ is in the temperature at which they gelatinise. Corn starch, for example, needs to be cooked at higher temperatures to gelatinise (from 62C to 72C with full gelatinisation at 95C), while flour has a lower gelatinisation temperature (51C to 60C). What this means is that flour will thicken your food faster at a lower temperature. I was always taught that you wanted to cook your corn starch thoroughly at a high temperature and I guess this is the reason why, and also why it is common in some Asian cooking where food is often cooked quickly but at very high temperatures in a wok.

On the internet a high amylose content is also often given as a reason for high gelatinisation temperatures. But looking through the literature amylose content was actually reported to be negatively correlated with granulisation temperature (here and here) but positively associated here, Wikipedia also went for a positive correlation but with no citation. So who knows? I guess that’s carbohydrate chemistry for you.

Another consideration is the thermal stability of the starch gel. If you are making something that is going to simmer for a good while and you add the starch early in the cooking process it is a good idea to select a starch that will not start breaking down during cooking. Potato starch, for example, thickens quickly and strongly but it will break down if kept at a high temperature for too long and you may still end up with a thin sauce at the end. Flour is relatively heat stable and rice starches are very heat stable, which is why rice starches are often used for gluten free thickening. Corn starch also has a high gelatinisation temperature but the resulting gel can break down if cooked too long. So, if you are using a starch in a long cook and you are worried about its stablity either monitor the temperature so it doesn’t get too high or decrease the cooking time.

Starches also bring flavour to a dish and the classic example of this is a roux. Traditionally a roux is made by cooking equal amounts of fat and flour over medium heat and it can form the base of a dish or be added later in the cooking process. A roux can be cooked for a minute or two, known as a blonde roux, and it is used primarily to thicken a sauce. But, because flour has proteins as well as starch, if you continue to cook the roux you will start getting our old friends the Maillard reactions and the mixture will brown and develop nutty flavours. The longer you cook a roux the less thickening power it will have, because of the starch will breakdown, but the more flavour it will impart to the dish.

The well-known example is the brown roux made for gumbo. In this case the flavour of the roux is more important than it’s thickening power as file powder and okra will help thicken the sauce towards the end anyway. Because the Maillard reactions are between a sugar and a protein, if you try this with pure starches, like corn starch, you’ll still get a thickening agent but no browning as pure starch doesn’t have the protein content that flour does.

The workhorses when it comes to thickening are the amylopectin molecules. Because of the size and ‘branchiness’ of amylopectin it does a good job of increasing the viscosity of a sauce. But what it doesn’t do well is impart strength to the sauce because the branches prevent the molecules from packing together too tightly. It is similar to what we saw with saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. The kinks in the unsaturated plant fatty acids prevents them from packing too tightly together which makes many plant fats oil at room temperature. Amylose, a much smaller compact molecule without extensive branching, is able to form a much tighter association with other amylose molecules and this can impart more strength to a starch gel. When serving a hot sauce or mashed potatoes, for example, this is not much of a consideration as you are aiming for viscosity not a strengthened gel. But this does become an important consideration when a starch gel begins to cool and this is because of another important starch process called retrogradation.

Retrogradation occurs when you let a fluid thickened by gelatinisation cool down. Gelatinisation is not reversible, that is once you cool down the mixture the starch granules will not reform. But what does happen is that the carbohydrates start to associate with each other again instead of with water. This contraction in the carbohydrate matrix reduces the space available for water in the starch matrix which forces some water out of the gel. The amylose molecules start associating again quite quickly and because of their compact nature they associate closely. Amylopectin takes a bit longer to reform some structure and when it does it tends to pack together much more loosely because of its branching structure. The consequence of this is that a starch gel low in amylose, made primarily of amylopectin, will be loose and runny while a lot of amylose will give you a much stronger gel thanks to the tight structures formed by the association of the amylose molecules.

Retrogradation is often desirable in the production of things like bread cereals, low carb rice and dehydrated mashed potato. But for the home cook it isn’t something that will matter straight away, if you thicken a sauce with starch or make mashed potato you wont be serving them cold but, as I said above, it becomes a consideration when food is allowed to cool. For example, the new structures that amylose forms during retrogradation alter the texture of leftovers. Leftover mashed potato is stiffer and grainier than when first served and this is because of retrograded amylose structures. Similarly, long-grained rice becomes hard when refrigerated over-night because of amylose. Sometimes the new structures formed during retrogradation are more stable than the original starch granule and this can be used to reduce the amount of digestible starch in food. If you cook and then cool things like pasta, potatoes and rice the retrograded amylose will be resistant to digestive enzymes in the gut. Essentially you are turning starch into fibre and so you are getting less calories and potentially reducing the glycemic response to the starch content of the food (if your interested here is one paper on the topic).

Retrogradation is also important to home cooks when the food will be cooled before eating. If you are making sushi, for example, the very low amylose content of short-grained rice means that they will retain some softness and stickiness when cooled, unlike long-grain rice. A cold long-grained rice sushi roll would be a little tough on the teeth with all that amylose conglomeration. Conversely, if you are making a pie that will be eaten cold then amylose is your friend. Apart from getting the thickening and timing right so that you don’t kill the starch gel with excessive heat, if you use a starch low in amylose you might end up with a runnier pie filling than you wanted. Bread also retrogrades after baking and this is how, over time, it goes stale. The starch molecules in the bread contract, force out water and the amylose molecules form their tight association; the net effect of this is dry, hard stale bread. Putting bread into the fridge only accelerates this process as the colder temperatures accelerate the re-association of the starch molecules.

Carbohydrates have a bad reputation, whether or not they deserve it I don’t know (but I guess it might make up a future post), but without them most of humans through history would have gone hungry. And, in moderation, they are not only nutritious but extremely useful for all sorts of applications in the kitchen. So having a good grasp of the behaviour of starch when preparing food is essential knowledge for any home cook.

Leave a comment