In my mind mayonnaise has always been kind of a Jekyll and Hyde sauce. We all know what mayonnaise is and we all have a bottle of mayonnaise in the fridge. But we also have homemade mayonnaise, a sauce that can be richer tasting but which can also vary greatly depending on what oil and flavourings was used to make it. They are really two completely different things. Most people are only familiar with commercial mayonnaise and so that’s what most people think of when they think of mayonnaise.

I’m not going to take sides on which tastes better, homemade or commercial mayonnaise, I like them both and use them both regularly and interchangeably depending, usually, on how much time I have. Admittedly commercial mayonnaise has more preservatives and other chemicals in it, but I’m not eating gallons of it, it is pretty convenient and yeah it tastes pretty good, so go commercial mayonnaise. Conversely, homemade mayonnaise has a flavour all it’s own, the ingredients are fresher, it’s creamier and the lack of stabilisers and preservatives, to me at least, make it seem more wholesome.

Mayonnaise is also very versatile and there are a whole bunch of different sauces you can make with it: aioli, remoulade, blue cheese and tartar sauce being just some examples. When making these types of sauces I have to ask myself do I want the underlying flavour to be store bought mayonnaise? Do I want to be putting expensive saffron in commercial mayonnaise? My answers to those questions is usually no.

So one path to becoming a better cook is understanding how to make a mayonnaise and to do that we need to consider mayonnaise as the next step in our emulsions journey. It is important step as it is the first emulsion in which we will need to get a good grasp of what emulsifiers are and how they help us stabilise emulsions. I touched on emulsifiers very briefly in Emulsions I and in this post we are going to take a much harder look at how emulsifiers work and why they are so important in our food. We will also take a good look at egg yolks, one of the basic ingredients of mayonnaise and one of the most common and most powerful emulsifiers we have at our disposal in the kitchen.

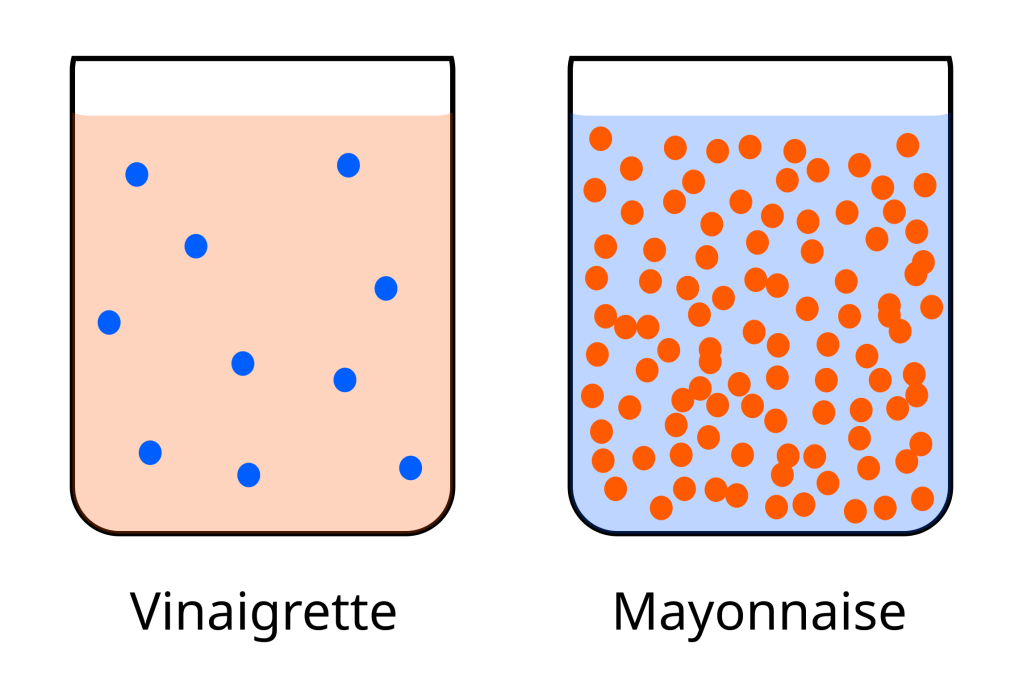

In the first emulsions post I talked about how an emulsion had a continuous phase and a dispersed phase. Which is a kind of complicated way of explaining that an emulsion is a mixture of water and oil and that you can either disperse oil through water, so there are little droplets of oil in water, or water through oil, where little droplets of water are dispersed through oil. A vinaigrette, because it is a simple mixture of oil and water without much in the way of emulsifiers, is a water-in-oil emulsion, one part water dispersed through three parts oil. A vinaigrette is thin because, when it comes to emulsions, the more dispersed phase that you get into the continuous phase the thicker the emulsion will be. A vinaigrette is three parts of oil with only one part water dispersed through the oil, so it is thin.

Roughly speaking, mayonnaise, just like a vinaigrette, can also be three parts oil and one part water, but, crucially, mayonnaise is an oil-in-water emulsion. In this case there are three parts of oil dispersed through only one part water. This makes mayonnaise much thicker than a vinaigrette because a large part of the emulsion, by volume, is in the form of oil droplets dispersed through the water phase. As we learned in Emulsions I keeping hydrophobic molecules dispersed in water is very energetically unfavourable and left to itself a mixture of oil and water will soon split and separate into two phases. In mayonnaise, the amount of oil that is dispersed through the water phase would be impossible to achieve without using emulsifiers to stabilise the emulsion.

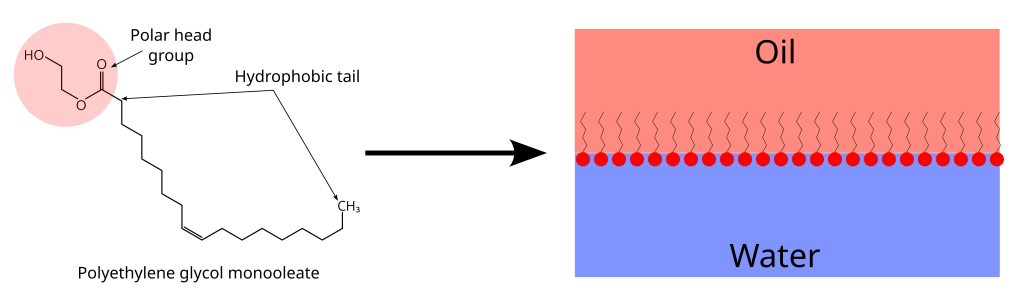

The theory behind emulsifiers is pretty simple. An emulsifier is a molecule that has a charged part and a non-charged, or hydrophobic, part. Emulsifiers work because they are able to interact with both water and with other hydrophobic molecules, like oil. So at any interface between, for example, oil and water emulsifiers will arrange themselves with their hydrophobic bit in the oil and their polar bit in the water. So instead of oil and water butting up against each other at their interface they are now separated by the emulsifiers. It’s probably easiest understood diagrammatically below.

Emulsifiers help us form emulsions in two ways. Firstly, emulsifiers reduce the surface tension of water which makes it easier to mix the oil and water. If you remember when we were looking at the vinaigrette we needed to put energy into the mixture to get the oil and water to mix. We needed to force the water into the oil, so to speak, breaking the bonds between water molecules and getting the water droplets surrounded by oil. Emulsifiers make it easier to get the oil into the water.

Secondly, once the emulsion has formed emulsifiers stabilise the emulsion by forming micelles. Micelles are just spherical structures consisting of an outer shell of emulsifers surrounding a droplet of the dispersed phase, in mayonnaise this is oil for example. The whole emulsion is more stable because the dispersed phase is no longer directly interacting with the continuous phase. The emulsifier is the go between, the Ned Flanders of the chemical world keeping everyone happy. A less anthropomorphic explanation is that micelles have a lower free energy so the second law of thermodynamics drives their formation and lowers the free energy of the whole mixture (see Emulsions I if you want to learn more about free energy). For our purposes you can think about it either way, we’re cooks not physicists.

Mayonnaise, in it’s simplest form, is just oil and egg yolk, the yolk being the water phase. So where are the emulsifiers coming from? Clearly it has to be the egg yolks and it turns out that egg yolks are a rich source of emulsifiers. I talked about eggs in one of my first posts and in that post I said that the egg yolk is a bag of water with proteins in it but that isn’t quite right. It is a bag of water with proteins in it but it also has a lot of little oil or fat droplets and that should sound familiar. Egg yolks are also an oil-in-water emulsion and, luckily for us, they are stuffed with emulsifiers that stabilise the egg yolk emulsion but they can also be used to stabilise other emulsions. When we make mayonnaise with egg yolks we are hijacking these egg yolk emulsifiers and putting them to work emulsifying our sauce.

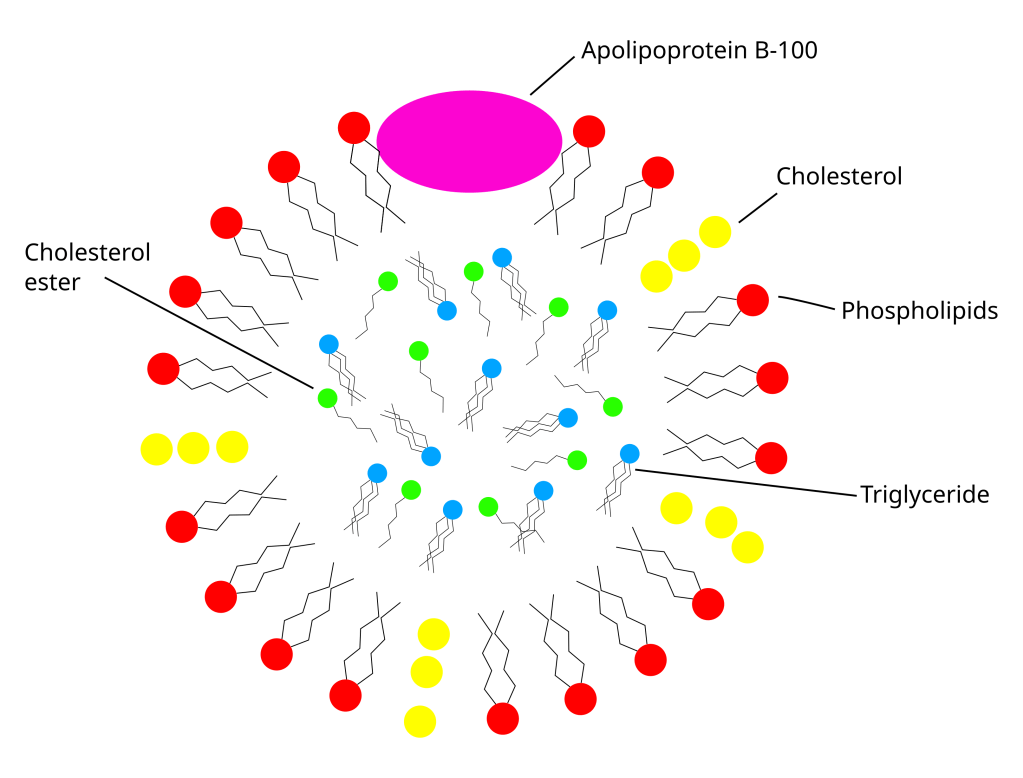

Much like blood you can easily separate egg yolk into a thin, clear yellow solution (referred to as plasma) and solid particles. The plasma mostly contains particles called low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) and if you squint at one of these particles you can see that they are actually kind of like a micelle. In the human body LDLs are formed in the liver where they are packed with cholesterol and set to circulating through the blood system (so blood too is an emulsion). As they circulate through the blood stream cells that need cholesterol will take them up as needed via specialised receptors on their surface. They are commonly known as the ‘bad’ cholesterol because excess amounts of circulating LDLs may lead to heart disease and stroke. Because egg yolks are packed with LDLs it was thought that they could contribute to health problems but if you like eggs don’t worry as eating eggs doesn’t seem to increase circulating LDLs in humans, despite what what was thought twenty years ago (if you want more on this see here). The solid particles in egg yolks contain another micelle like structure called HDL (high-density lipoprotein) that differ from an LDL by the amount of protein embedded in the micelle.

It appears that the LDL particles are the constituent of egg yolks that provide a lot of their emulsification power. I went down a bit of a rabbit hole with this as I wasn’t sure how a micelle could emulsify anything, it’s already emulsifying its load of cholesterol, but what is likely occurring is that the LDL particle breaks down at the oil/water interface liberating it’s load of hydrophobic molecules into the oil and the phospholipids and other emulsifying proteins of the micelle then emulsify the oil droplets. How this exactly happens is still not really understood but if you want to go down my rabbit hole you can start here. HDLs in their particle form aren’t as good emulsifiers as LDL but salt will dissolve HDLs freeing phospholipids and proteins that are good emulsifiers. So adding some salt to your yolks is a good strategy when making mayonnaise or using egg yolks as emulsifiers.

Even if we still don’t really understand the fine details of egg yolk emulsification we do know that they work and for centuries chefs have known from experience that egg yolks make great emulsifiers. As Harold McGee points out a single egg can emulsify dozens of cups of oil. A lot of cook books, internet sites and even Google’s Gemini AI say that a single egg yolk can only emulsify one cup of oil. But this is wrong. One egg yolk on its own will only emulsify one cup of oil (roughly speaking) but this is because the egg yolk is also the water phase and any more oil will overload the water phase. If you keep adding oil and, importantly, water to maintain the ratio of oil to water (roughly about 3:1 oil to water) you’ll end up with gallons of mayonnaise from that one egg yolk (Harold McGee describes his experiments on this here). When it comes to emulsification the egg yolk is a superstar.

As usual I’m 2000 words in and we still haven’t made a mayonnaise so lets start with an egg yolk, some neutral oil and a whisk. What we want to do is start dispersing the oil in small droplets through the egg yolk and give the emulsifiers a chance to start forming micelles that will stabilise the sauce. If you just dump all the oil into your egg yolk there is no way that you are going to break up the oil into small droplets and get it dispersed through the water phase. So you need to add oil to the mayonnaise slowly, a little bit at a time, beating vigorously as you go. As more and more oil droplets are formed you’ll be able to start adding more oil each time as the existing droplets help disperse the new oil. There is nothing wrong with a mayonnaise with just egg yolks, oil and a bit of salt but often you want to add more flavour. But when adding flavourings remember if you add a water based ingredient, vinegar or lemon juice for example, you will need more oil to maintain the thickness of your sauce. When you’re happy with the consistency of your emulsion that’s it you’ve made mayonnaise.

It’s worth making a mayonnaise this way, with a whisk, at least once, if only to experience the pain and gain an appreciation for our recent ancestors who didn’t have access to immersion blenders. Judging by the amount of YouTube videos on the topic, it’s pretty well known now that you can make mayonnaise using an immersion blender and avoid all that whisking. To do this you put your egg yolk, salt and flavourings in a tall jar and then pour your oil on top. Let the oil settle at the top for a little while and then put your immersion blender flat on the bottom of the jar and turn it on. The immersion blender causes a vortex that gradually pulls the oil down into the water phase and the rapid mixing disperses the oil through the water phase. I’ve put put one of the YouTube videos below and in this you can see it takes about fifteen seconds to make mayonnaise. I imagine there are a lot of older chefs who weep while watching it but it also shows that there is no excuse for not trying to make your own mayonnaise at least once.

So that’s it really, a lot of science and fifteen seconds with an immersion blender and you have some mayonnaise. The only thing left to talk about is how to care for your new emulsion. Probably the most important thing to talk about is food safety, whenever you are dealing with raw egg products you need to take the possibility of salmonella infection seriously. You can get pasteurised eggs, which is one option, but if you don’t have access to these you should use fresh, uncracked eggs and keep the mayonnaise refrigerated as much as possible. I’m also conservative when it comes to storing homemade mayonnaise. It’s so easy to make and it’s just a cup of oil and one egg yolk so I feel pretty comfortable just throwing out leftover sauce. If I just want a bit for a sandwich or something, well that’s where commercial mayonnaise is useful.

The other consideration is how to keep your mayonnaise emulsified. One simple error is putting a mayonnaise-based sauce on something that is too hot. If you remember my frying an egg post, yolk proteins will start coagulating at around 60C/140F. Coagulation is the process where proteins, when heated, start to unwind and lose their structure. Some of the most effective emulsifiers in egg yolk are proteins so if you put your mayonnaise into an environment that exceeds this temperature your going start losing emulsifiers and the oil will break free of it’s emulsified droplets and run free. This can easily happen if you put some mayonnaise on something you have just taken off the heat so let things cool down before adding a mayonnaise based sauce or it will split.

That’s it for mayonnaise and the second step in out emulsions journey. I’ve barely scratched the surface of mayonnaise, what oils to use, the different types of flavourings, how it behaves when frozen (not well), making mayonnaise with something other than egg yolks and lipid bilayers are all topics for a later day and you could write a whole post on the LDLs as bad cholesterol issue as well as the science behind commercial mayonnaise. But it’s a fascinating subject and emulsification is such an important part of not only food production but also basic biology. The movement of hydrophobic substances around the blood system and the importance of lipids and cholesterol to living beings are all massive subjects that rely on some of the same science as our humble mayonnaise. Having said that I think we have covered enough for today so I’m going to go and have a sandwich.

Other stuff

SciHub

I’ve struggled with how to link to academic papers that are behind a paywall. I have very strong opinions on this that I’ll address elsewhere but if you want to read more about the science behind egg yolk emulsification I’ll give you the DOI references of the papers. DOI references are a permanent address of a documents online location. If you have institutional or private access to these documents you can find the papers using these strings. If not you can go to SciHub and get access to them there, they are on SciHub because I checked. The legality of doing this is a bit grey, it’s like the Pirate Bay for academic papers, so it is up to you. The DOI strings for the papers I’m referencing above are ‘10.1016/s0308-8146(03)00060-8’ and ‘10.1021/jf0719398’.

Leave a reply to Jason Mulvenna Cancel reply