About Quick bites

Quick bites are shorter very specific posts that add some extra information that was too much for a regular post but which are worth knowing anyway. They can also highlight some important biological or chemical principle that can be referred to rather than explain the same thing over and over in different posts.

If you have read any of the posts on this blog you are probably starting to realise that when we are talking about chemistry in cooking a lot of the time we are actually talking about proteins. For this reason it is important that we have a clear idea of what a protein is, how it behaves when heated and what happens when you add acid or salt to proteins. So in this short post I’m going to give a broad overview of what a protein is and why they behave the way they do in certain circumstances. There is a bit of chemistry but I’ve tried to keep it brief.

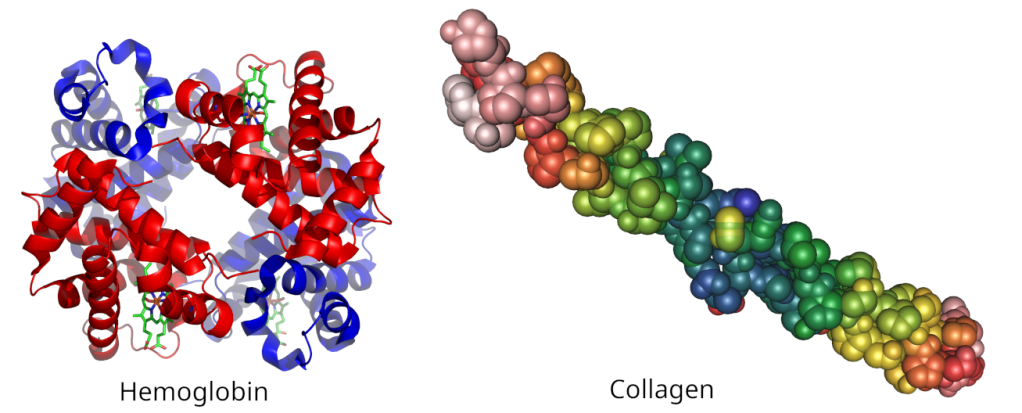

Proteins are, on a molecular level, giant molecules that are found in every living thing, including us. Proteins have a wide range of functions in a living organism. They provide structure in things like connective tissue and hair, they provide motive force in muscles, hormones and other signalling molecules are often proteins, they catalyse essential chemical reactions in the body, they act as transport molecules, like haemoglobin in the blood, and the antibodies that protect from disease are also proteins. Without proteins there would be no life.

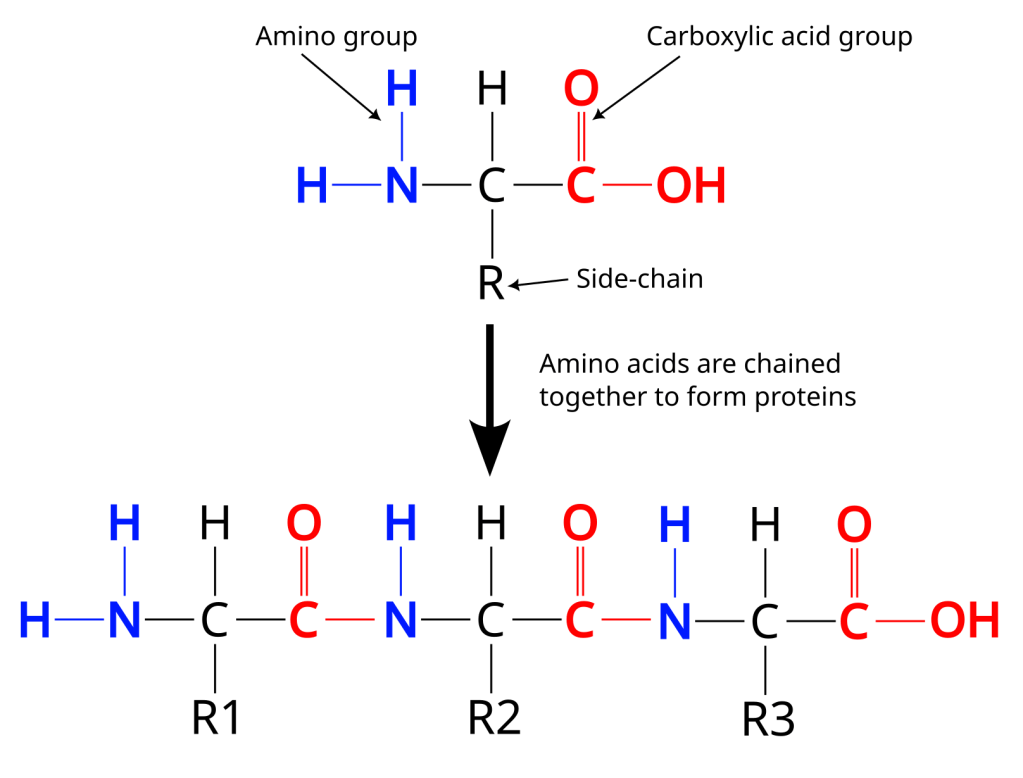

Proteins are made up of smaller building blocks called amino acids. Amino acids all have the same overall structure (see below), a central carbon atom linked to an amino group (the NH2), a carboxylic acid group (the COOH), a hydrogen atom and one of about 20 different chemical structures, called the side-chains of an amino acid (the R). Each side-chain has different chemical properties, some are positive, some are negative and some have no charge. Proteins are formed when amino acids with different side-chains are combined into long chains that then fold into some three dimensional structure. The sequence of amino acids in a specific protein is what is encoded in DNA, so DNA is the blueprint for all the proteins in our bodies, and also in the animals and plants that we eat. We can synthesise all but nine of the amino acids we need to make our proteins, so one of the points of eating is to get these nine amino acids from the food we eat.

Once formed proteins will fold into some three dimensional shape that is essential for whatever function they are fulfilling. Some are globular, they are like balls of wool, like many of the proteins in egg white and yolk, and some are long and stretched out, like proteins found in things like hair, muscle and skin. These 3D shapes are all stabilised by various chemical interactions between different parts of the protein. Proteins can also form complexes with other proteins and these are also stabilised by the same type of interactions.

There are several different types of protein interactions. Some rely on the charged areas of the protein, positive parts of the protein being attracted to negative parts of the same or another protein and vice versa. Another class of interactions are called hydrophobic interactions. In these interactions uncharged, or neutral, parts of the protein prefer to interact with other neutral molecules rather than water. In globular proteins, for example, non-charged parts of the protein chain are buried in the center of the protein away from water.

When we cook proteins we are adding enough energy to disrupt these chemical interactions causing the protein to unfold, or, using the technical term, denature. If it gets hot enough the protein itself may start to break down into it’s constituent amino acids. In really broad terms denaturing proteins is why we cook food, we are breaking up the proteins in our food, making our food more palatable and easier to chew and digest.

Because a lot of protein interactions rely on charge, salt and acidity can also interfere with protein interactions. Salt is made up of charged atoms (Na+ and Cl-) and when dissolved in water these atoms can neutralise charged areas on a protein, preventing ionic interactions with other proteins. If these interactions are important for stabilising the proteins three-dimensional shape then salt will also cause the protein to denature.

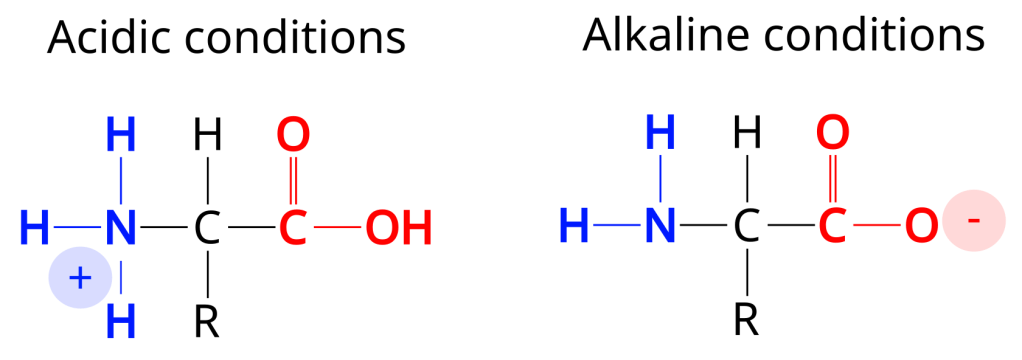

Acidity, is a little more complex to understand, but basically acidity messes with the positive and negative chargers on the protein. In highly acidic conditions parts of the protein may have an extra hydrogen atom causing it to have a positive charge, acidic groups on the protein that normally have a negative charge will be likewise bonded to a hydrogen atom so the negative charge will be neutralised. The opposite happens in low acidity (alkaline) conditions. So the effect of acidity, greatly simplified and really it depends on the protein, means that a protein will have a net positive charge in acidic conditions and a net negative charge in alkaline conditions. Either way it is likely that the complex interactions stabilising the protein will be disrupted and the protein will partially or fully denature.

There are entire textbooks written on protein chemistry so this is nothing but a crude sketch of proteins and protein chemistry. But for now it will be enough to let us get on with some cooking science. Hopefully as we continue our journey through the science of cooking we’ll refine this sketch and get a better understanding of proteins.

Leave a comment