There is probably no more feared food group than the plants that come from the Brassicaceae family. Also known as the cruciferous vegetables, this family, surely a practical joke played by God on children, includes the plants that bring us cabbage, Brussels sprouts, kale, mustard greens, arugula, turnips, kohlrabi, broccoli, cauliflower and many other childhood nemeses. If you want to disappoint a child tell them that there is a cruciferous vegetable for dinner. This also works on many adults.

Although they are feared, it is true what your mother said: the brassica1 are incredibly good for us. They help prevent cancer, they improve our heart health and they contain anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory molecules (see here for an exhaustive review of these). The problem is that the molecules that bring us the health benefits are the very same ones that give the brassica such a bad name. The molecules that are good for us are the same ones that can often make the brassica bitter and pungent. Anyone wanting to include the brassica in their diet need to come to terms with these molecules.

The fact that so many of us have bad memories of childhood meals containing cruciferous vegetables is a testament to how challenging things like cabbage, kale, Brussels sprouts and mustard greens can be to prepare. This is a shame. If you can work out how to cook them, cruciferous vegetables can become the stars of the dish. Cabbage, especially, is an incredibly versatile vegetable that is the main ingredient in kimchi, sauerkraut, okonomiyaki, golabki and coleslaw. But, yes, even Brussels sprouts can be a star if prepared the right way.

The root of the problem, when it comes to cruciferous vegetables, is the system that they have evolved to deter predators from eating them. Plants, known for their immobility, have some challenges when it comes to finding food, reproducing and protecting themselves from predators. A plant can’t bite off your arm, a plant can’t go to a singles bar and a plant can’t move to greener pastures. Plants can’t even run away. There are no fight or flight decisions for a tree.

To achieve their goals plants have instead become masters of chemistry. They produce a staggering wide array of molecules that they use to manipulate the more mobile organisms around them. Plants make parts of themselves that they don’t want eaten taste bad, in the best-case scenario, or toxic and potentially fatal, in the worst case. Conversely, if plants want animals to eat parts of them, they make those parts taste good. Fruit, for example, is the way plants tempt animals into dispersing their seeds for them. Some plants can even persuade animals to deliver their sperm to a suitable egg. Bees being the most famed animal participants in the sex life of plants.

In this vein, to protect themselves from predators, the brassica have turned some of their cells into stink bombs that release a flood of bitter and pungent chemicals when an insect starts to eat them. They manage this by synthesising a group of sulphur-containing chemicals, called glucosinolates, that they store in specialised vacuoles, a water filled “sack”, within their cells (see here for a primer on plant cell biology if you need it).

When the cell is damaged, say by an insect eating it, and the vacuole is ruptured, the glucosinolates mix with the other contents of the cell. When this occurs an enzyme called myrosinase breaks the glucosinolates down into a variety of different pungent molecules that are potent pesticides, killing or otherwise deterring many insects species that might try to snack on the plant.

What is bad luck for an insect is good luck for humans. Though the brassica have gone to great effort to develop these defences against insects, the molecules that they produce also have some beneficial side effects on humans. This is a pretty common occurrence. A willow tree doesn’t care if we have a headache2, a cannabis tree has no interest in our Saturday night and the lime tree was not thinking about scurvy in 18th century sailors. Nonetheless, all these plants have yielded molecules with beneficial, or at least interesting, effects on the human body. The glucosinolates are another example of plant molecules having fortuitous side-effects in humans.

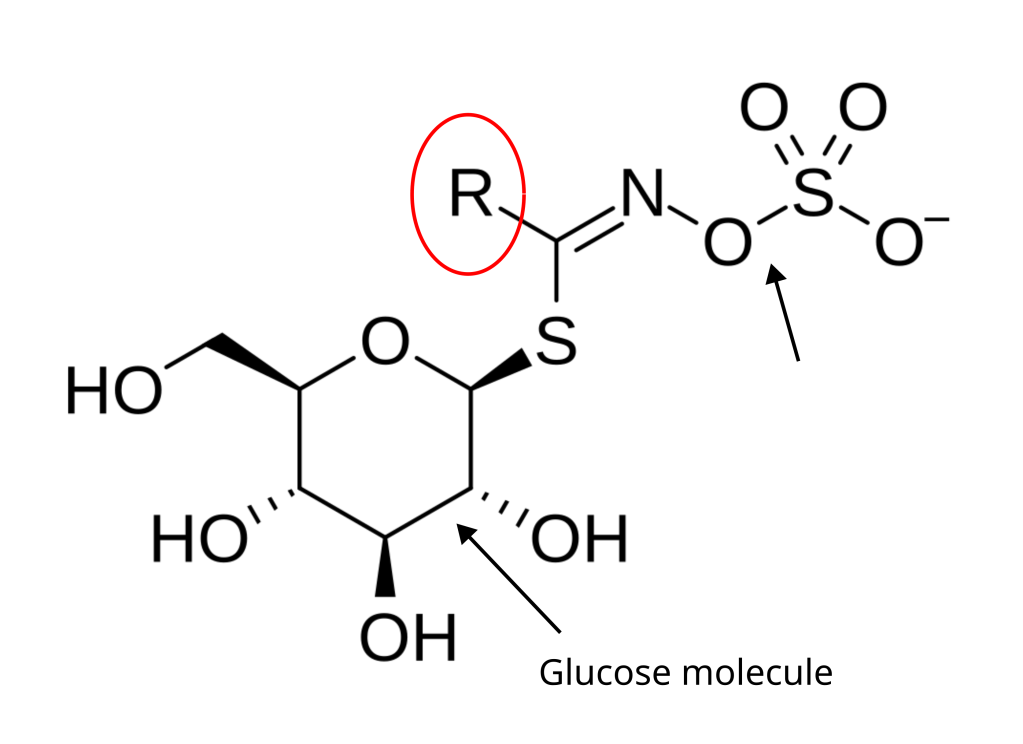

There are about 120 glucosinolates found across all species of the Brassica. Each plant contains a subset of them and the mix of glucosinolates that a plant contains contributes to the flavour profile of that plant. Each glucosinolate is synthesised from a molecule of glucose and an amino acid (molecules I’ve had a bit to say about here and here). Though they all share a similar chemical structure, different glucosinolates differ in the composition of a side group that gives them, and their break down products, unique chemical properties (you can see this in the figure below).

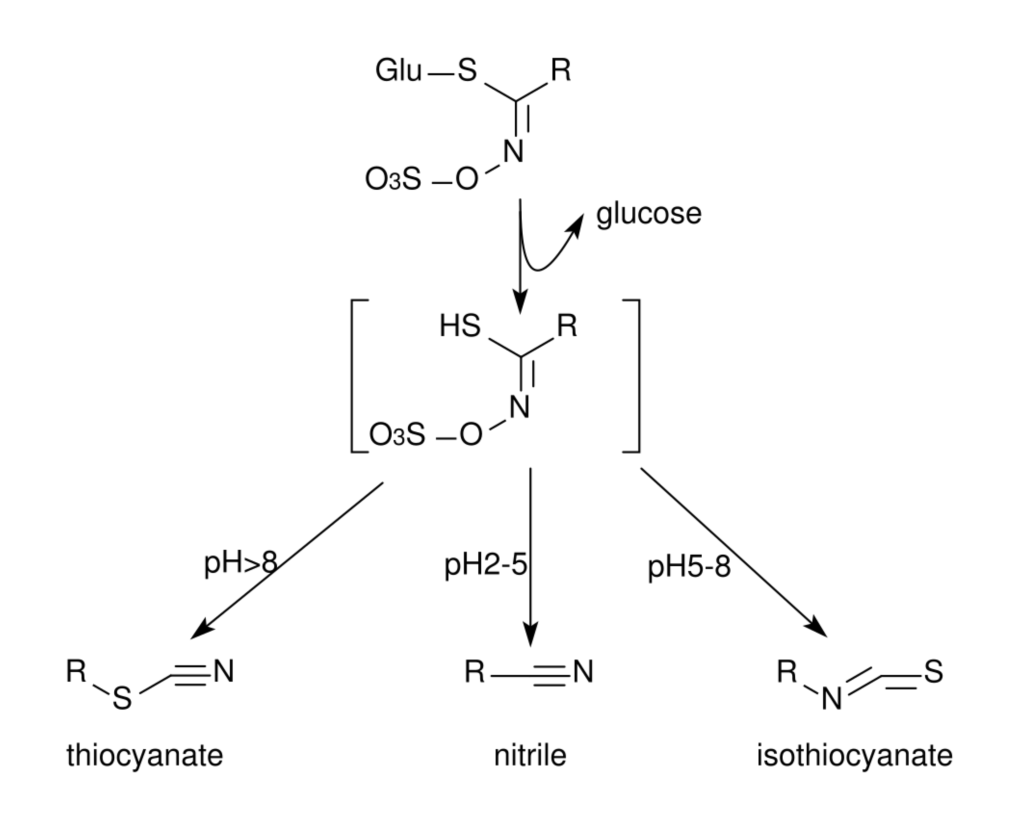

When a glucosinolate is exposed to myrosinase it is hydrolysed3 releasing a molecule of glucose and another short-lived molecule (called thiohydroximate-O-sulfonate if you want to show off at dinner parties) that spontaneously breaks down into a range of different molecules based on the surrounding conditions; heat and acidity having the greatest effect on what products are created. In general, though it’s not always the case, the intact glucosinolates contribute to the bitterness of the brassica and the breakdown products to the pungency.

It is the glucosinolates, and their breakdown products, that are so good for us but they are also the molecules that make the brassica such a challenge to use in our cooking. The bitterness you find in something like a Brussels sprout, which has an enormous amount of glucosinolates, is not something that can be ignored.

Like starving soldiers eating their boots, humans generally like to boil something till it tastes good (if this doesn’t work, brine it then try fermentation). Sometimes, this works fine. Onions, for example, lose their astringency and become sweet when cooked for a long time. The brassica, of course, are too awkward for that. When boiled the glucosinolates leach out of the plant and into the water. Although this was often seen as a positive thing, a way of decreasing the bitterness of brassicas, we know now that a lot of the nutritional benefits of the plant leave with the glucosinolates.

There is another problem with boiling your cruciferous vegetables. Boiling inactivates myrosinase and instead the glucosinolates undergo thermal breakdown into nitriles. These molecules, apart from not being quite as good for us as the isothiocyanates, contribute to the musty aromas you get when you boil a brassica, think of the smell of boiled cabbage. If you go too far, which many people still do in an effort to remove bitterness, these sulphur containing nitriles breakdown further into the rotten egg molecules dimethyl disulphides. The result is a smelly, mushy dinner and some childhood trauma.

In theory, if we want to maximise the health benefits of the Brassica, we should eat them raw. Chewing breaks up cells and stimulates the breakdown of glucosinolates and provides the full complement of breakdown products that can work their magic on your system. You’ll also get the full effect of their bitterness and pungency. So be prepared if you are eating something like Brussels sprouts or mustard greens. Good luck getting the kids to eat a raw Brussels sprout too.

Cutting and slicing cruciferous vegetables will also cause the breakdown of the glucosinolates as the cells are damaged. The more cutting you do the more cells will be damaged. Once cut, rinsing in water can reduce the bitterness and pungency as liberated molecules are washed away, though you are losing some of the goodness when doing so. Treating something like cabbage with acid after cutting can increase the amount of pungent molecules. After the initial breakdown of the glucosinolate by myrosinase, higher acidity promotes the formation of isothiocyanates, the molecules that give mustard its punch, over less pungent and mustier smelling nitriles.

These days, instead of boiling, high heat is the recommended way of cooking a lot of cruciferous vegetables. High heat methods, like steaming, roasting or stir frying, result in a much lower rate of degradation of the glucosinolates, so it’s better for our health, but crucially it brings in other flavours that help to counterbalance the bitterness. In particular, Maillard reactions bring nuttiness and savoury flavours and caramelisation of the natural sugars of the plant that will enhance its sweetness. This is a great way of dealing with Brussels sprouts where, because they have both bitter glucosinsolates and bitter break down products, it is almost impossible to escape bitterness in some form.

You can, of course, use flavour in many other ways. At least four out of the five basic tastes can help reduce bitterness. Salt suppresses bitterness (which I covered in this post) so make sure to season your Brussels sprouts. Salt may also enhance sweetness, and it seems obvious that by adding sweetness, i.e. sugar, this will help mask any bitterness. I don’t really like adding too much sugar in my cooking but a sweet sauce could do the trick.

Acid seems to be able to reduce bitterness by interfering with bitterness receptors (see here for my post on the taste receptors) and, in the case of the brassica, acidity plays an important part in what breakdown products are formed after the breakdown of glucosinolates by myrosinase. So acidity may result in fewer bitter break down products. Finally, fat can also reduce bitterness without affecting the saltiness or sweetness of a dish. We aren’t too sure why this happens but it definitely happens. A good example of this would be the mayonnaise in coleslaw maybe tempering the bitterness of raw cabbage.

The brassica have been an important food source for thousands of years. The Romans loved cabbage. So much so that Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, suggested that babies be washed in the urine of cabbage eaters to prevent weakness and improve health. Make of that what you will but it is undeniable that the brassica are very good for us, when eaten that is. As is usual in this world, that which is good for us is so often not the best tasting but with a little care and attention to detail things like cabbage, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower and broccoli can actually be tasty as well as nutritious. Just don’t boil them.

Footnotes

- The Brassica is technically a genus within the Brassicaceae which contains many of these plants. But things like radish, rapeseed, horseradish and, for the scientifically minded, the model organism Arabadopsis thaliana are all contained with different genera in the Brassicaceae. I’ll just refer to the ‘brassica’ because it’s shorter than typing Brassicaceae over and over and that genus contains most of the plants I’m talking about. ↩︎

- Aspirin was developed from a molecule call salicin that was originally found in the willow tree. ↩︎

- If something is hydrolysed it means that a water molecule is added to the molecule, normally resulting in a splitting of the molecule. The opposite is a dehydration (or condensation) reaction where two molecules are joined by removing an -OH from one and a -H from another, -OH and -H add up to H20 of course. ↩︎

Leave a comment