I’ve been to a lot of places and I’ve eaten a lot of things. I thought that there was nothing left that could give me a culinary jolt. I was wrong.

I’m in Osaka, Japan. I’m travelling with my family and another from our home town of Brisbane. We had landed at Narita Airport two days earlier and plunged into the system of subways, bullet trains and buses that seems to merge all of the cities of Japan into one giant metropolis. Swept along in this rapidly flowing mass of humanity we had finally, after a few pit stops, surfaced at Shinsaibashi-suji. A covered shopping street, that makes a gash through the Central Ward of Osaka and bleeds boutiques and large department stores.

I wasn’t too happy to be trudging along this 600 meter temple to consumerism. We have a Uniqlo in Brisbane I pointed out. But mine was a lonely voice of complaint in our little touring group. The kids, in particular, couldn’t be denied. Not with the pop culture stores in Parco and the Pokemon centre in Daimaru. So I trudged along and tried not to look too disgruntled.

Luckily, the other dad in our group had done some research and suggested we go to a steak restaurant for lunch. He said that Kobe beef was supposed to be pretty good. I’d heard of Kobe beef, of course, but I didn’t know a lot about it, some variant on Wagyu I thought, which I’d tried before. But a steak lunch did sound a hell of a lot better than standing outside the Miffy store while my child spent all my money, so I readily agreed.

We took a side-street off the main mall, went down a steep staircase between two other ground level restaurants and entered a small space containing two teppanyaki stations with seats around them. Room for twenty people maximum. I still wasn’t expecting that much, the name of the restaurant was “Oh! My Steak” which didn’t inspire much confidence, but they had beer and so I was happy. Then, twenty minutes later, 120g of carefully cooked Kobe beef and a bit of soy sauce changed what I considered a good steak forever. It was that good.

I’ve since learned that Kobe beef is the name given to waygu beef that comes, and only comes, from Tajima cattle1 born and raised in Hyogo Prefecture. To be designated Kobe beef it needs to be raised to exacting standards and is certified with a Nojigiku (wild chrysanthemum) seal and a 10 digit identification number denoting its lineage. My ignorance can, perhaps, be partly excused by the fact that it is very hard to find authentic Kobe beef outside of Japan. The Japanese understandably eat it most of it themselves. Elsewhere in the world, wagyū beef is sometimes sold as Kobe or Kobe-style, but it isn’t Kobe beef unless it has the Nojigiku seal and it is rare as a comfortable seat for dads in Parco outside of Japan.

What makes wagyū beef in general, and Kobe beef in particular, so special is the large amount of marbling. The fine layers of fat that runs all through the meat. It is this marbling that is the secret to why Kobe beef is so good and the production of Kobe beef is basically an exercise in producing meat with as much marbling as possible.

As such, Kobe beef is the archetypal example of the role that fat plays in our meat cookery. It is fat that gives Kobe beef it’s incredible buttery tenderness, the almost melt in your mouth texture. It is also fat that provides much of the flavour of Kobe beef, an intense sweet and buttery umami flavour that you don’t get with other types of beef. Although taken to it’s extreme in Kobe beef, fat plays the same roles, providing texture and flavour, in any meat that we cook and so it’s something worth understanding.

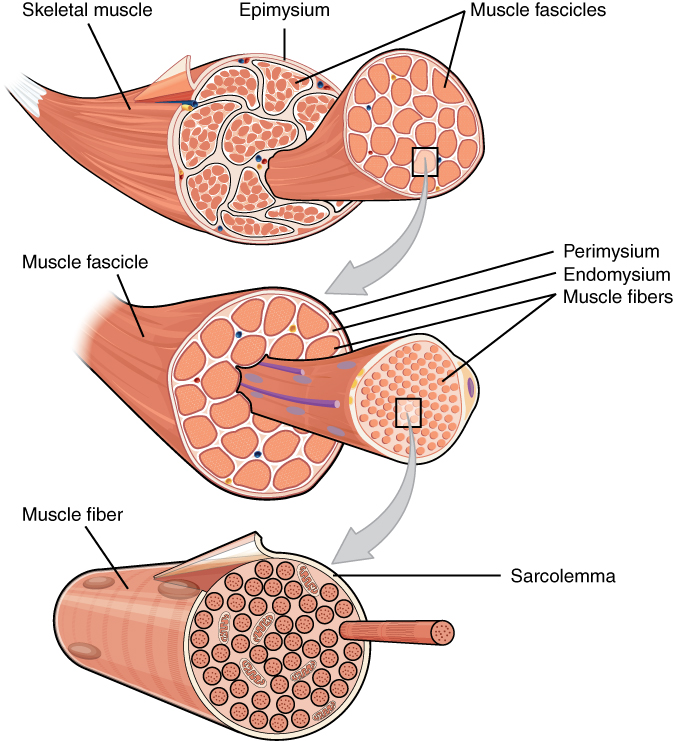

I’ve talked a lot about meat in previous posts (here and here for example), so, briefly, an animal muscle is made up of bundles of long protein-filled muscle cells, called fibres, that are themselves bundled into larger groups that make up the muscle. Interspersed between the fibres and the different bundles is connective tissue. The narrative so far has been that frequently used muscles will have larger muscle fibres and more connective tissue that secretes collagen. Together they make these muscles tougher to eat than less frequently used muscles that have small fibres and much less connective tissue and collagen.

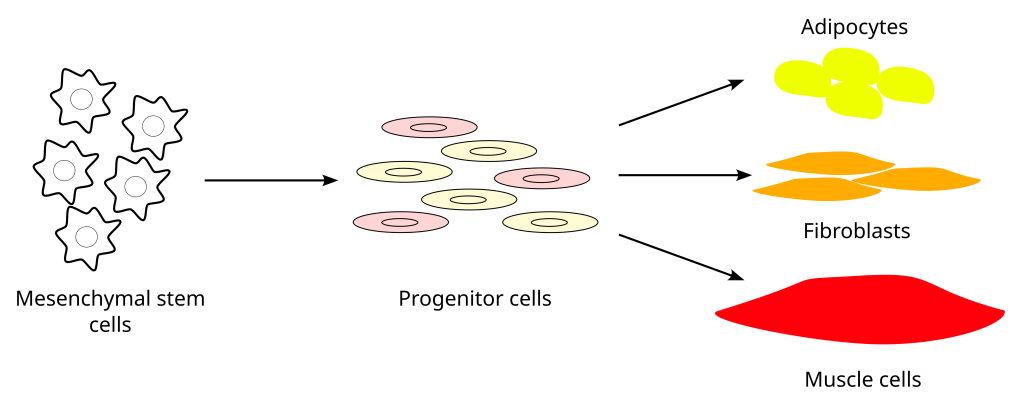

This isn’t the whole story though. To understand Kobe beef we need to understand marbling. How do you get fat to form in between the bundles of muscle fibres? Well the answer to this has to do with the connective tissue. Marbling forms from a specific type of connective tissue that is made up of cells called adipocytes, a type of cell that is capable of storing fat. Early in embryogenesis, pluripotent2 cells called mesenchymal stem cells can develop into cells with a myogenic potential, they can become muscle fibres, or with an adipogenic-fibrogenic potential. The latter cells are the ones that become connective tissue. They do this by further differentiating into fibroblasts, that make up the connective tissue that we’re familiar with, or adipocytes, that cells that form the connective tissue that causes marbling3.

For a specific organism, the decision to form an adipocyte or a fibroblast is really a question of prioritising energy storage (an adipocyte) or muscle structure (a fibroblast). Because there is a limited pool of parental cells, it is also a competitive process that, apart from genetics, can be influenced by the amount of energy available and other environmental factors. Much of this decision making occurs during gestation and in the first 250 days of a cows life (the “marbling window”, as it’s known). This means that maternal nutrition and the way that the calf is treated are absolutely critical for ensuring the formation of plenty of adipocytes that will eventually provide the marbling.

Apart from forming adipocytes (what is called hyperplasia4), you also need to fill the adipocytes (a process called hypertrophy5). You need to stuff the adipocytes with fat as an empty adipocyte will not give you much marbling. But adipocytes aren’t just in muscle tissue, they are whereever fat accumulates in an animal body. In mammals, there are roughly four places that fat is stored: visceral fat, the fat surrounding our organs, subcutaneous fat, the fat just below the skin, inter-muscular fat, fat between muscles and intramuscular fat, the marbling we’ve been talking about. In a given organism, total fat appears to be divided between these four areas with intramuscular fat, our marbling, generally receiving the smallest share.

Adipocytes from different parts of the body have different physiological properties and behave differently. This is important for Kobe beef as the muscle adipocytes in Kobe beef tend to store monounsaturated fat, mostly a fatty acid called oleic acid. If you remember the post on animal and plant fats, the fatty acids in unsaturated fats are kinked and don’t pack together very well which means they will have a low melting point. Plant fats, for example, are unsaturated and typically have a melting point below room temperature, which means they are an oil. Because the intramuscular fat in Kobe beef is unsaturated it melts at around 25C, much lower than other types of fat found in the mammalian body. So, when you eat some medium rare Kobe beef the intramuscular fat literally melts in your mouth. Unsaturated oils are also better for you so, if you trim the intermuscular fat off your Kobe beef, you could almost persuade yourself it’s healthy.

OK, we can see now that the challenge for beef producers is to maximise both the number of adipocytes that form in the muscles of their cattle and the amount of fat that is deposited into these adipocytes. The strongest determinant of all this is a cows genes. The genetics of a cow puts a limit on the amount of adipogenesis (the creation of adipocytes in the muscle) and lipogeneisis (the creation of fat in these adipocytes) that can be achieved in that individual.

Having said that, producers still want to fully exploit their cattle’s marbling potential. It stands to reason that if you want fat you need to feed your cows high energy food, so grain- not grass-fed, and there is evidence that a low protein:energy ratio can increase marbling6. Likewise, there is pretty good evidence that a vitamin A deficiency also promotes marbling, at least when the cow is young7. Other potential factors are age when weaned, other vitamins like C and D, castration, age and weight at slaughter and many more. But, despite all these variables, when it comes to ensuring good marbling, the best thing you can do is treat your cow well; a stressed cow is not a well marbled cow.

Just as in humans, stress in cows causes a rise in adrenaline, and other hormones such as cortisol, that shift the metabotolic emphasis, in the muscles at least, to energy consumption rather than energy deposition. In a stressful situation you need your muscles so you can either fight or run away. So, making the intramuscular fat available as glycogen seems to be a sensible thing to do in that situation, but it is death for marbling. Even worse, cortisol might also shift the location of any fat deposition that is occurring away from intramuscular adipocytes to visceral ones8, meaning that it is harder to restore the marbling after a stressful event.

Stress can be even more harmful when the cow is young. For example if a cow experiences respiratory illness within the first 250 days of it’s life the differentiation of adipocytes will be irreversibly shutdown, in favour of fibroblasts, severely affecting the amount of marbling that is possible later in life. Stress also interferes with insulin signalling which is crucial for triggering the production of fats and their uptake by adipocytes (I wrote about this on my post about UPFs). It’s a giant topic but, in general, a stressed animal makes for poor eating, a lack of marbling being just one of the side products of a poorly treated animal9.

So, what do the producers of Kobe beef do that makes their steak so good? You might hear that they feed their cows beers and give them daily massages but, sadly, both of these are myths. The major achievement of Kobe beef producers, and Japanese waygu producers in general, is identifying and maintaining a breed of cow, the Tajima strain of the Japanese Black in the case of Kobe beef, that is able to generate extensive marbling. Without the genetics, which we poorly understand, it wouldn’t matter how the cow was treated or fed, the level of marbling you see in Kobe beef would just not be achievable. You can see this clearly in the following table, which shows that you get more than three times the marbling in wagyu breeds than you do in something like Angus cattle.

Ironically, the initial discovery of the Tajima strain, and its marbling genetics, was a bit of an accident. It may come as something of a surprise, as you wander down Japanese food streets containing one steak restaurant after another, but meat eating in Japan is a very recent development.

Throughout most of Japan’s history not a lot of meat was eaten, partly because of the tenets of Buddhism, but also as a result of government policy. Emperor Tenmu, for example, in 675 CE, banned the consumption of all meat except for deer or wild boar. A ban that was strengthened by subsequent emperors. Though religion is often cited as a reason for the ban, in a small nation with limited resources focusing consumption on renewable foods like fish and vegetables was probably also sound agricultural management.

In a background, then, of limited beef consumption, Tajima beef was “discovered” in the 1860s when Westerners were granted access to Yokohama port. Being westerners they wanted beef and because eating beef was rare at the time in Japan, cattle from the relatively isolated Tajima province were shipped to Yokohama. I bet the westerners in that port couldn’t believe their luck when they had their first Kobe beef steak and I’m assuming more orders quickly followed. The farmers, noting that the westerners liked fat cows, started feeding their cattle barley and, just like that, Kobe beef was born.

The relative isolation of Tajima meant that the cattle there were a reasonably pure breed, with little genetic input from outside the region. Beginning in the early 20th century the lineage of cattle in the region started to be meticulously recorded and managed to maintain the marbling qualities that make the beef so special. A part of this management was prohibitions on breeding with other types of cattle. Kobe beef can only come from pure bred Tajima cattle with a documented lineage. These policies have been so well implemented, and documented, that the three major blood lines in the Tajima region, accounting for 90% of Tajima cattle, can be traced back to a cow called Naka-Doi, a sire10 born in 1920.

As we learnt when considering bananas, all this genetic purity can have its downside. Inbreeding is a concern for all wagyu cattle, especially since the 1980s when demand for wagyu beef really took off, but the problem is even more pronounced in Tajima. One recent study found that 95% of all calves in the region are descended from only 20 different sires. This inbreeding has led to congenital health problems like cryptorchidism, the fancy word for undescended testicles, that can impact the fertility of the herd.

It’s not just genetics though. To produce Kobe beef cows need to be raised according to strict guidelines, mostly focused on the things we considered above: diet and the reduction of stress. Tajima cattle remain with their mothers for a longer period than other cows and farmers maintain a calm and stress free environment including plenty of fresh air, clean bedding, gentle handling and, sometimes, regular brushing11.

Their diet is a strictly controlled and consists of rice straw, for fibre, and corn and barley, for energy and a slow build up of fat. Sometimes sake kasu (sake lees) are used though this is more for flavour than for fat development. To allow time for the buildup of intramuscular fat, Tajima cattle are also allowed to live for longer. Generally they are slaughtered around the 30-32 month mark, contrasting with 18 months which is a very common age of slaughter in Australia.

After all that, the beef from Tajima cattle is graded and only that beef that meets the highest standards of quality and marbling receives the Nojigiku seal, the mark that all officially verified Kobe beef must display. It must be a tough job, producing Kobe beef, though it is reassuring to think that there is something that is still made to exacting standards12. Where quality has been maintained and prioritised despite the temptation to increase production and profits but comprise on quality. It certainly was a wonderful surprise for me on that day in Osaka, but now I’m going to have to fly back every year to get my fix. Maybe I’ll finance it by reducing my child’s shopping budget, how many Pokemon trinkets does one person need?

Footnotes

- A purebred strain of Japanese Black cattle. It is one of the six cow breeds that are native to Japan and it is one of the four breeds that are collectively known as Wagyu, a word that basically translates as “Japanese cow”. ↩︎

- A pluripotent cell is just one that can develop into one of several different cell types. ↩︎

- I’ve simplified this greatly but you can read more about it here ↩︎

- A general term that indicates an increase in the size of an organ caused by an increase in the number of cells. ↩︎

- The increase in the size of an organ caused by an increase in the size of the cells as opposed to their number. If you are lifting weights, for example, your cells are undergoing hypertrophy. ↩︎

- Presumably by causing a small protein deficiency the emphasis will be on fat deposition and not muscle development. ↩︎

- As a cow ages vitamin A can actually inhibit intramuscular fat deposition so it’s a bit of a balancing act when it comes to vitamin A. ↩︎

- Stress and cortisol have been long thought of as important in human obesity as well. Though it is unlikely that obese humans have great marbling as cortisol promotes the deposition of visceral fat meaning an increase in the amount of abdominal fat. ↩︎

- See here for a good review on the effect of stress on meat quality. ↩︎

- If you a breeding cattle, a “sire” is the male parent of a cow and the “dam” is the mother. ↩︎

- Which may have given rise to the myth that Tajima cattle are massaged. ↩︎

- There only about 3000 head of Tajima cattle produced annually. ↩︎

Leave a comment