I’ve been watching ‘Knife Edge’ on Apple TV, a documentary that follows the trials and tribulations of Michelin star hopefuls. It is a guilty pleasure; reality TV with some Michelin star gloss, but you do get to see the incredible effort that is required for a restaurant to get a Michelin star, let alone two or three. A couple of things struck me when I was watching. Firstly, why would anyone put themselves through the stress and the drama? Can you not run a profitable restaurant with a high standard of food without the Michelin approval1? It also got me thinking about flavour. Human perception is famously malleable and does the whole mythos of the Michelin guide alter the way we perceive the food in a starred restaurant? Is Michelin starred food really that much better, or do we just think it’s better?

Come to think of it, it’s not just fine dining. I have a partner who loves wine, so I’ve spent a lot of time at cellar doors in Australia and in other countries. I’ve also bought many bottles of wine at these cellar doors, bottles of wine that sadly didn’t quite live up to the memory once I got them home. Not that they were bad, normally, just not quite as earth moving as they were at the vineyard. It’s almost as if being on holidays, drinking wine in a beautiful vineyard with a bucolic agricultural vista while an enthusiastic wine maker describes why this is the best wine I’ll ever taste is somehow distorting my flavour perceptions. Is such a thing possible? Surely my coldly logical scientific mind can’t be fooled this way?

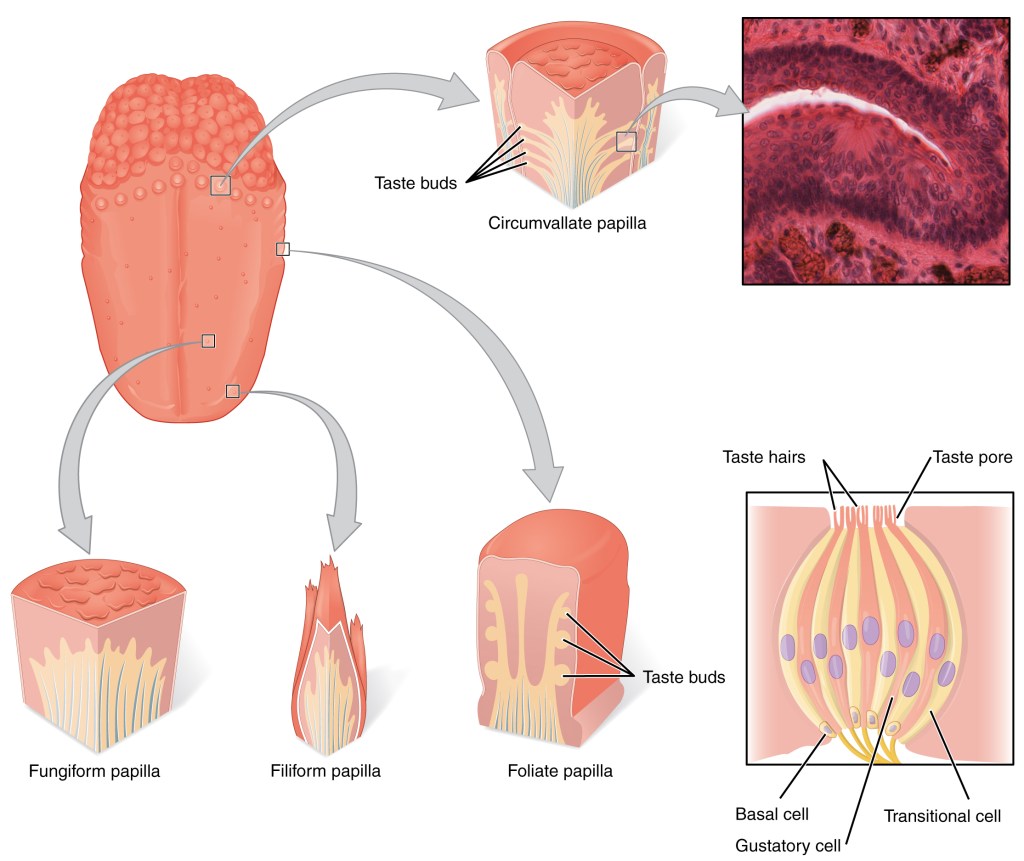

In my umami post I discussed how taste receptors on our tongue and oral cavity enable us to sense salty, bitter, sweet, sour and umami in our food. I pretty much left it at that, mostly out of laziness. Talking about a small set of receptors that stimulate a small set of tastes in our brain is easy. It makes sense and it’s easy to write a blog post on. Flavour on the other hand is a whole different proposition. Although we use “taste” and “flavour” interchangeably, taste really just applies to the five tastes, flavour is everything else. Flavour is not only the sum of all the sensory input that we receive while eating a meal but, and this is where it starts getting really complicated, our past experiences and the expectations we had for the meal can also alter how our brain experiences the flavours of that meal.

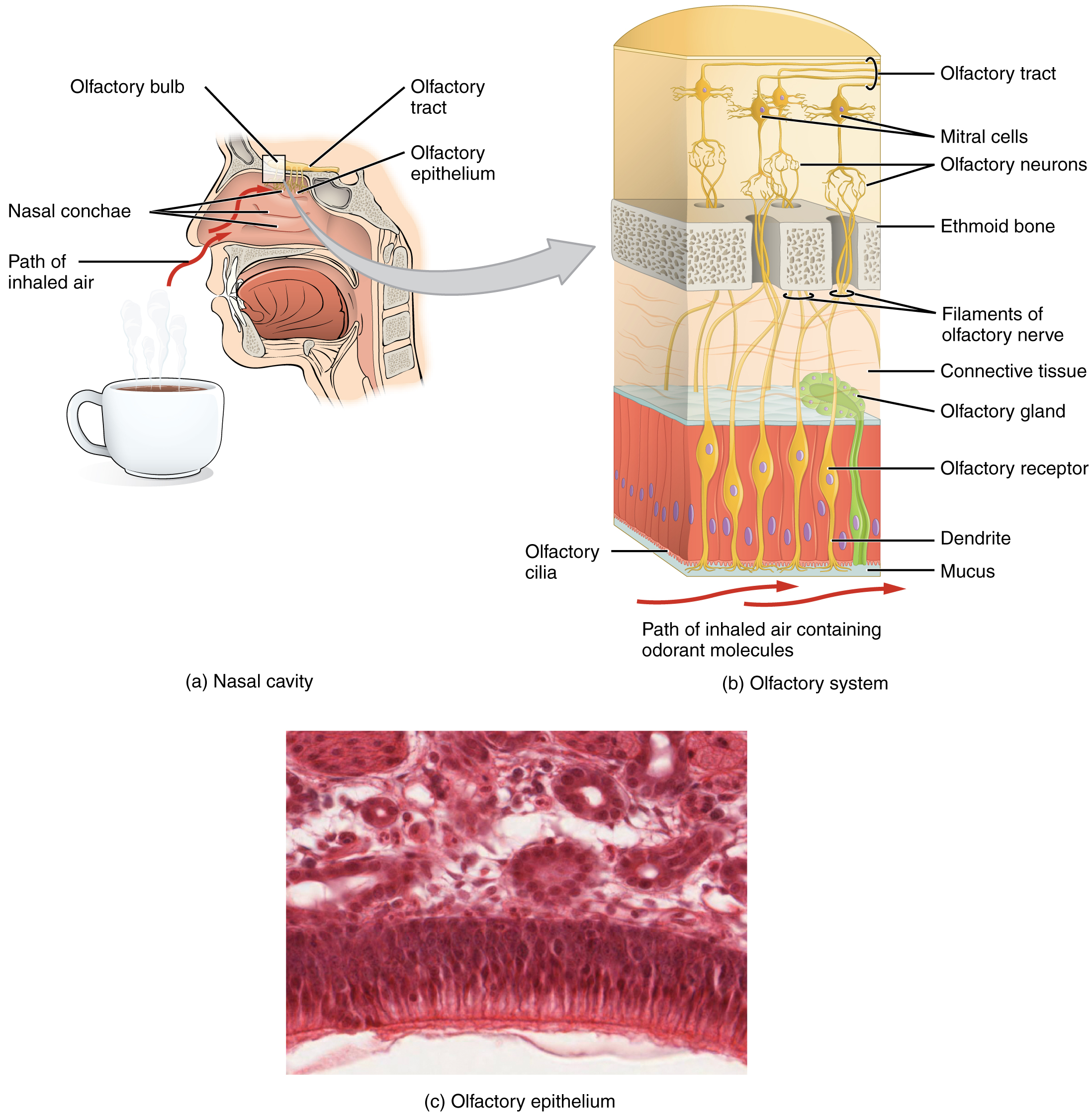

If you are a chef, or even a home cook, interested in building flavour then you need to pay attention to a whole lot more than just the taste receptors in our oral cavity. One of the biggest levers we have for influencing the flavour of a dish are aromas. Our sense of smell comes from roughly 400 receptors that are concentrated in a part of our nasal cavity called the olfactory epithelium. Air-borne molecules that we breathe in bind to these receptors which send signals to our brain that elicits the perception of a smell. Traditionally, it was thought that humans could sense around 10,000 unique smells but some recent research, that, it must be said, is somewhat controversial, suggests we may be able to detect trillions of smells2.

Regardless of how many smells we can smell, our sense of smell is crucial to our perception of flavour, and you’ll often see the statistic that 70-80% of flavour comes from our sense of smell. There isn’t much hard evidence to back up these exact figures3 but it is indisputable that smell has a major influence on our perception of flavour. For example, those who develop anosmia, the loss of the sense of smell, report a devastating effect on their ability to perceive flavour4 and, if you want to try it for yourself, just catch a cold and notice how much your flavour perception is affected by nasal congestion that prevents molecules reaching your olfactory epithelium. If your not willing to go this far in the interests of science you could also just hold your nose while eating something.

Given the importance of odours to flavour perception, it is no surprise that chefs have been all over our sense of smell for a long time. Fine dining restaurants have gone to great lengths to harness our noses in the service of their food: atomisers, smoke-filled domes covering dishes5, scented dry ice and even scent infused cutlery and charred wooden serving plates are all strategies that have been used to get aromas into our nasal cavities. But apart from these rather extreme measures, aromatics and aromas have always been an important part of cooking. Anyone who has sautéed onions and garlic has experienced the release of aromatics, and hence flavour, that this process brings to a dish. Similarly, garnishing with highly aromatic herbs, toasting nuts and spices to liberate fat soluble aromatics and using heat to cause Maillard reactions and caramelization are all designed to increase the aromatic profile of a dish.

We can even use aroma to make our dishes healthier. Chefs have long known that the aroma of fruit increases the perceived sweetness of the dish. That is aromas can make a dish seem sweeter without adding sugar. One way we can take advantage of this is by substituting small amounts of fruit, or fruit essence, for sugar in our own cooking. It’s important to realise that no, or fewer if using actual fruit, sweet receptors will be stimulated when we do this, we are relying on a purely mental association. For this reason, the person eating the food needs to already have an association with the aroma and sweetness or it wont work. This effect has attracted a lot of research interest as it is a way of reducing the sugar content of processed foods.

It doesn’t end with our sense of smell and taste though. Texture, for example, uses a combination of touch and hearing to provide feedback on the physical properties of our food. Crispiness and crunchiness are actually two different textures and it is our sense of hearing that helps us distinguish between the two. Crispness, especially, provides feedback on the freshness of our food, no one likes eating a mushy apple for example. The mouth is also one of the most enervated areas of the body and it is packed with many different sensory receptors6 one class of which are mechanoreceptors that give us our sense of touch. These receptors are not only useful for things like speaking but they also provide rich feedback about the physical properties of our food. Things like the hardness, size, viscosity and graininess of the food.

So our sense of touch, hearing, taste and smell are play a part in the sensation of flavour and texture. That leaves just one: sight. You may not think that sight has much to do with flavour perception but sight is the sense that, probably more than all the others, helps set our expectations of the food that we are going to consume. So what? You may be thinking. What’s expectation got to do with anything? Well it turns out that our expectation of what we are going to eat can actually influence our perception of flavour as we eat or drink. A very simple example of this would be a bowl creme anglaise. When we see some creme anglaise we are expecting a silky, smooth and sweet experience. If we detect some chunkiness when we eat we might start thinking that something is wrong. Lumpy or grainy custard may not be what we were expecting and the contradiction of our expectations alters how we are perceiving the flavour of the food.

Things become more complicated when our expectations aren’t grossly contradicted. What happens when we are expecting something great and we get something that is pretty good? Scientists have been looking at this for a long time in the context of wine. Price is a powerful expectation setter. We expect that quality rises as price increases and we expect this relationship to hold not only for cars and phones but also food and, most notoriously, wine. When it comes to wine, scientists have shown over and over again that price information affects our appreciation of a wine, even when that price information is incorrect (there is a review of many of these studies here). That is, if people are told they are drinking an expensive wine they tend to rate its flavour highly even if it is actually a cheap wine. This not only goes some way to explaining why my wine tasted better at the cellar door, but it also suggests that we build an expectation of what a flavour experience is going to be and, unless this expectation is not grossly contradicted, then we are happy to think we are experiencing what we were expecting to experience.

It’s not just wine and price though, expectations can be set by many, many different things and going through the literature it feels like a scientist somewhere has experimentally tested all of them. Packaging is something that has been extensively studied. Consumers report better satisfaction from foods that are labelled as ‘eco’ or ‘sustainable’ and the perception of the calorific content of food can be altered by labelling such as “gluten free” or “low carbohydrate“. This tendency for consumers to over-estimate the qualities of food labelled as sustainable or “eco-friendly” has been called the “halo effect” and consumers consistently say that foods labelled this way taste better7. The story does not stop at packaging, multiple studies have shown that genetics, psychological state, food colour, the environment in which food is consumed, price, social setting, how the food is plated, how hungry we are8 and even how hungry someone else is could all affect our expectations of food and how we rate the flavour of that food.

I don’t think we have really worked out what is going on though. It can be hard to design a good experiment when we are dealing with things like self-reported “satisfaction”9. A lot of the studies are examining hedonistic impressions, that is how much the subject “likes” the food, rather than specific biological changes that can be quantified. But even when quantitative experiments are attempted, say measuring differences in brain activity, a subject stuck in an MRI machine is likely to be having very different experience than if they were sitting in a nice restaurant. In the wine studies there are other problems: wine can be “squirted” into subjects mouths which means they are missing out on the aroma of the wines10 and the subjects, often university students, may be biased towards price because they just don’t know a lot about wine; wine connoisseurs do much better in these studies than lay people11. When it comes to experimenting on human perception I’m glad I’m a chemist because it is really hard.

Nonetheless, there does seem to be a lot of evidence that flavour is affected by a whole lot more than just our sense of taste and smell. What we find in the literature also accords with what we have all experienced in daily life. Food does taste better when I’m hungry, wine does taste better when I’m sitting in a lovely vineyard and, despite my attempts at objectivity, food does seem to taste better when I’m experiencing all the ritual of a fine dining restaurant. A meal is an experience, engaging all our senses, and it is affected by our previous experiences, our expectations and our mood. There is even evidence that if we miss out on this experience, because we’re watching TV or scrolling on a phone, it interferes with our levels of satiation and we become hungry again sooner12.

So, is culinary excellence a fools game? Are Michelin starred restaurants just hoodwinking us with their elaborate rituals and food presentation? Well, of course not, and I’m not just saying that to stop Gordon Ramsay coming around to teach me a lesson. A good restaurant should be able to make food that tastes13 better than what we can make at home: they can source the best ingredients, they can make their own stocks, they can develop interesting dishes and they have the people and the equipment needed to get the parts of a meal together at the same time without leaving bits of it sitting in a warm oven while the rest comes together. Most importantly they should be able to make the same dish to the same standard over and over again (so much so that this is one of the criteria for a Michelin star14). These are the reasons you go to a good restaurant, and a Michelin starred restaurant is just the same, but better (in the Michelin guide’s opinion).

The Michelin guide specifically excludes ambience from the judging criteria, but restaurateurs go to great lengths to build exactly that in their restaurants. Why do they do this? My guess is that restaurateurs understand that food is an experience. If you went to a farm-style restaurant or a BBQ joint you’d be a bit surprised if small portions of artfully arranged haute cuisine started arriving at the table. Likewise, if the restaurant looks like an art gallery with a maître d and immaculately turned out wait staff, you’d be surprised to see a salad bar lurking in the corner15. Restaurants create a space that builds an expectation of the type of food that they serve and then they try not to disappoint those expectations.

When you think about it it’s a bit of a risky game, disappointed expectations are death for a restaurant but, if you can satisfy them, the experience created is likely to increase the perceived quality of your food. A successful Michelin starred restaurant is really a place that creates an expectation of fine, and creative, food and manages to satisfy that expectation in their customers. And they can do it over and over again. So, a Michelin star is kind of a guarantee that you are going to have a good experience and, unless you are an expert taster or the restaurant really mucks up your order, you’ll likely find the food delicious because that is what you are expecting. It’s all about the theatre, but, you know, I’ve yet to go to a fine dining restaurant that has replicated the experience of a cold beer on a hot day while cooking a steak on a grill in my backyard, maybe that’s an idea for a restaurant?

Footnotes

- A question at least two people in the show answered in the affirmative. ↩︎

- Whether it’s 10,000 or a trillion it’s still a bit of a mystery how our 400 receptors can stimulate such a wide variety of unique smells but part of the answer may be that molecules are able to bind multiple receptors, producing many unique patterns of interactions and thus stimuli to the brain. ↩︎

- See here for an in depth discussion on that issue. ↩︎

- Though, interestingly, those who are born without a sense of smell seem to develop the ability to perceive flavour regardless, suggesting the brain is able to compensate in some way. ↩︎

- The dome is called a cloche and if filled with smoke it is a smoking cloche. ↩︎

- We’ve come across one class of these when we looked at chillies that activate heat sensitive receptors in our mouth. ↩︎

- I hope that I am not being too cynical when I suggest that companies are very interested in this research because it also shows that the halo effect also make consumers happy to pay more for these foods. ↩︎

- There is even evidence that when we are hungry our body is more receptive to bitter tastes, i.e. potentially bad food tastes better. This paper describes differences in brain function related to flavour in starved mice for example. ↩︎

- See the post on experimental design in nutrition studies for a discussion of this topic ↩︎

- Which we now know is very important. ↩︎

- In fact I suspect anyone that is trained to distinguish or rate food and wine along objective criteria would be less susceptible to expectations. As is so often the case people who develop a very high level of expertise in something can probably only be judged properly by people with an equal level of expertise. When it comes to food and wine this means mere mortals, like me, probably don’t even know how good, or bad, something actually is. ↩︎

- The idea is that the distraction interferes with the proper establishment of a memory of the meal. ↩︎

- In the tasting of flavour sense! ↩︎

- The Michelin criteria are: the quality of the ingredients, mastery of flavour and cooking techniques, the chef’s personality in the cuisine, value for money, and consistency across the menu and over time. ↩︎

- Unless it was an ironic salad bar with super expensive and well presented salad bar items. ↩︎

Leave a comment