I’ve written more than a few posts on food science now and it is something of a scandal how I haven’t yet talked about acids in cooking. Acid ranks right up there with salt when it comes to seasoning our food and yet I’ve skirted the issue, mentioned it here and there, but haven’t really tackled it head on. I think that this is a learned reflex. The acidity or alkalinity of a solution has a profound impact on proteins (and other large biological molecules like sugar and DNA) so protein isoelectric point calculations, pH calculations, acid-base titrations and equilibrium problems were some favourite exam question in undergraduate biochemistry. Discussion of proteins and acids thus trigger memories of long, lonely nights of desperate revision before exams.

I’m obviously a sucker for punishment because, as a postgraduate, I went into protein structure determination and so big part of my life has involved dealing with proteins under conditions of precisely controlled acidity. I think all this explains my involuntary tic whenever acids and bases are mentioned but these psychological scars are no excuse, acids are a crucial for understanding many parts of cooking and flavour and so we need to have a good look at them and that’s what I plan to do in this post.

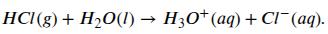

If we want to start at the beginning we should look at what an acid is and, just to make things simple, there are a three different definitions of an acid. Here though we’re going to use the simplest definition of an acid which is it’s a compound that releases hydrogen ions (H+) when dissolved in water1. An acid that you may have heard of is hydrochloric acid (HCl). When put into water a molecule of HCl will dissociate into it’s constituent parts, that is a proton (H+) and a chloride ion (Cl–). We can describe this reaction in the following formula:

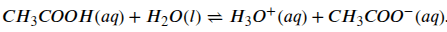

When hydrochloric acid dissociates the concentration of protons in the solution will increase (the H3O+ in the formula2). If you put a lot of HCl molecules into water all of them will dissociate and for this reason it is called a strong acid. On the other hand, when a quantity of some other acids are put into water only a portion of the molecules will dissociate and these are called weak acids. Acetic acid, the acid found in vinegar, is an example of a weak acid and it’s dissociation is reversible. This means that in water acetic acid will be in equilibrium between it’s associated and dissociated state. We can see that in the following formula:

Whether it’s strong or weak an acid will increase the concentration of protons in an aqueous solution but the proportion of a weak acid that is dissociated will depend to some extent on the concentration of protons already present in the solution.

Now there is a Yin to an acid’s Yang and that is something called a base. Like protons in acids, a base is something that will increase the concentration of hydroxide ions (OH–) in an aqueous solution. A strong base is something like sodium hydroxide (NaOH–, aka caustic soda), which, just like a strong acid, will dissociate completely in water and increase the OH– concentration:

Just like acids, there are strong and weak bases but they all act to increase the concentration of hydroxide ions in solution. We can also see that an acid will neutralise a base, and vice versa, because if you stick a proton and a hydroxide ion together you get water (H2O).

This is almost as far as we want to go as cooks but we do need to know a bit about the pH scale (and it’s inverse the pOH scale). As we’ll see the acidity of a solution is pretty important and the pH scale gives us a way of describing the acidity, or alkalinity, of a solution. The pH scale does this by quantifying the concentration of protons in water (the pH stands for “potential of Hydrogen”). The pH scale runs from 0 to 14 with 0 being highly acidic, i.e. more protons than hydroxide ions, and 14 being highly basic, i.e. more hydroxide ions than protons3. At pH 7 an aqueous solution is said to be neutral and at that pH the proton concentration is equal to the concentration of hydroxide ions (OH–)4. There’s a bit of chemistry behind all this, which I tried to explain briefly in the previous footnote, but in the kitchen if you know that a pH less than 7 is acidic and a pH greater than 7 is basic you’ll be fine.

When I first started learning this chemistry I was a bit confused. All this talk of protons and hydroxide ions was fine but, lets be honest, all I wanted to know was how an acid could possible corrode an entire body and let someone get away with murder. Not that I wanted to use it in a practical sense, but Walter White and Jessie did not talk about free proton concentrations when they were trying to dispose of a body with hydrofluoric acid in Breaking Bad. How can some protons and hydroxide ions make acids and bases the standard plot device for disposing of a body in countless movies and TV shows? Well the answer is surprisingly relevant to cooking and it all stems from the effect that all those charged species in an aqueous solution do to proteins (and other large biological molecules).

To get a handle on this let’s use proteins as an example of a large biological molecule, the discussion about proteins is pretty much the same for sugars and DNA and other materials. In the protein chemistry post, and many others, I talked about how proteins are long chains of amino acids that are folded into a three-dimensional shape that is stabilised by chemical bonds between different parts of the protein. If we take another step out, we can see that larger structures are also formed when folded proteins interact with other folded proteins and these are held together by some of the very same types of chemical bonds.

Some of these interactions rely on a charge, or partial charge, being present on the protein. The two most important interactions for stabilising a protein, hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions, both rely on these charges. These charges often arise because some chemical groups on the protein side-chains are weak acids and some are weak bases; so a single protein can have multiple acids and bases on different parts of it’s surface. Because they are weak acids at a particular pH these acids and bases will either possess a charge or not (i.e. they will be dissociated or not). If the charge is important for stabilising the three dimensional structure of the protein and it is not present because of the pH of the solution then the protein will be destabilised.

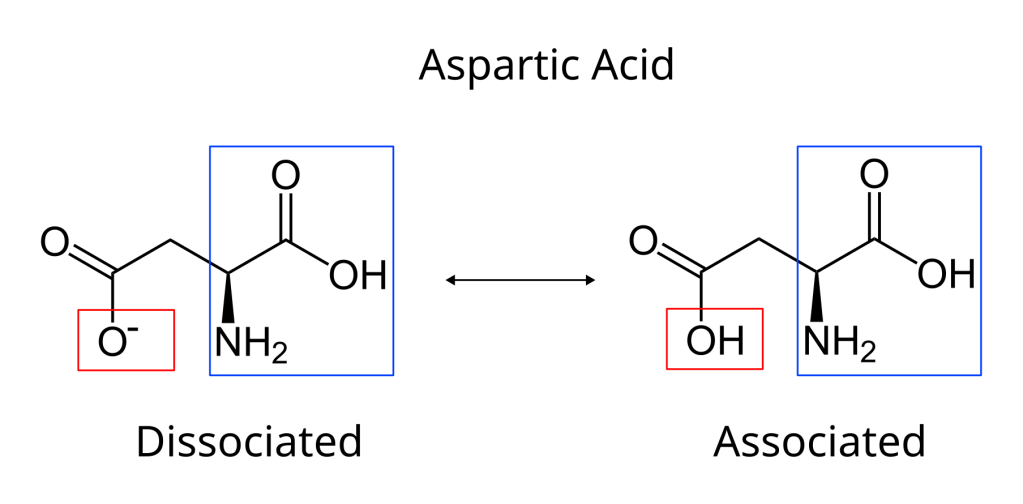

For example one of the 20 essential amino acids is called aspartic acid (easy to remember it’s an acid because it is right there in the name). Aspartic acid has a hydroxyl group that acts as an acid. So if we add a protein with this side-chain to pure water this group will donate a proton and become OH–, i.e. it will have a negative charge because it lost it’s hydrogen (see the figure below). But as we decrease the pH (i.e. increase the amount of protons) at a certain point aspartic acid will start accepting protons again and it will lose it’s charge. A basic side chain will do the reverse, when pH is low it will accept protons because there are a heap of them floating around and it will gain a positive charge. At high pH’s it will have no charge because it will have lost it’s hydrogen. In general, a protein will be positively charged at low pHs, because all basic side-chains will be positive and the acidic ones neutral, and will be negative at high pHs because all the acidic side-chains will be negative and the basic ones neutral5.

It is, of course, all a bit more complicated than this because the precise pH when an acid or base dissociates is different so the isoelectric point6 of different proteins will vary (calculating this point for a specific protein making a convenient exam question). But we don’t need to worry about this, all we need to know is that changing the acidity of a solution changes the charges on a protein dissolved in that solution. These charges are holding the proteins together so if they change the protein will start to denature, it will begin to unwind and whatever structure the protein has will start to disintegrate7. This is how acids and bases are able to corrode biological material.

Acids and bases also have a few more tricks up their sleeve. Firstly, depending on the acid, the chemical species released when the acid dissociates can have some bad effects. Hydrofluoric acid (HF) is an example of this. Although it is a weak acid in dilute aqueous solution8 it is still a highly hazardous chemical because of it’s ability to penetrate deeply into tissue where the fluoride ions (F–) released by it’s dissociation bonds with calcium and magnesium9. These bonds play havoc with cellular functions but it also means that fluoride can draw the calcium out of bones and remove calcium from the blood stream causing hypocalcaemia and potential heart failure. It’s also a gas at 19C so it’s easy to breathe in, something you do not want to do.

The dissociation of strong acids is also a very exothermic reaction. I’m not going to get into the thermodynamics of acid/base reactions but when a strong acid goes into water its dissociation releases a lot of heat. This means that a strong acid will also burn whatever it is corroding. When you are using strong acids in the lab you need to be very careful, never add water to acid (it will explode) and very carefully add acid to a water when you want to make an acidic solution (the same goes for strong bases). The dissociation of weak acids is usually endothermic, it takes energy from the environment rather than releasing it, so you don’t need safety goggles when mixing vinegar and water in the kitchen.

Everything I’ve said for strong acids also works for strong bases. A strong base will neutralise positive charges on the protein, effectively destroying ionic interactions and hydrogen bonds just like an acid. In fact if you are a budding serial killer the bases are probably more effective at disposing a body. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) is probably more effective at dissolving a body according to various internet sources. If you are interested there is a good thread here and a good article here on chemically breaking down a corpse but this is a food blog so we should get back to food.

You’ll often hear that acids cook food and from what we’ve seen this is not so far from the truth. Remember from the frying an egg post that whenever we cook proteins we are aiming to denature the proteins, in that case using heat. An acid does exactly the same thing but it does it by altering the electric potentials of a protein and disrupting the bonds that holds it together. It also stands to reason that anytime we want some protein structure acid or base will be our enemy. We’ve seen this with pasta and other doughs, where we want a strong gluten network, we’ve seen it in egg white foams, where we want egg proteins to stabilise our air in water mixture, and we’ve seen it in milk where acidity can denature casein proteins and cause the milk to curdle.

Conversely, because acid kind of cooks proteins (and other biological macro-molecules), we can use it when we want to disrupt biological structures. So to make meat more tender we add acid to marinades where it will begin breaking down the proteins in the muscle. Ceviche is a classic example of using acids instead of heat to cook finely sliced fish (or other seafood). The challenge when using acid, for marinading and making ceviches, is timing. Acid will turn your protein to mush if you leave it too long so you need to work out what time works for different situations. With ceviche there is the added complication of how thick to slice your seafood, too thick and the acid will turn the outside to mush before it does anything to the interior (there is a good article on the timings for ceviche here).

Although I’m talking about cooking using acid we need to be aware that cooking with heat also kills any microbes that may have contaminated your food. Acid will not have the same sterilising effect. Heat kills bacteria, see the bacterial growth post, but acid will often not get rid of all contaminating bacteria or parasites. Not so important if you are marinating whole meats, that you are going to cook with heat anyway, but if your making ceviche you absolutely need to have the freshest, food grade fish you can get because the acid won’t kill all the microorganisms that may have contaminated the seafood.

We’ve seen that bases have pretty much the same effect on biological material as acids do but we don’t make ceviche with sodium hydroxide, we always use an acid. The reason for this is that acids and bases are also flavours. In the umami post we had a look at some receptors that, when the interact with molecules in our food, cause the different flavours: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami. It turns out that the molecule that activates our sour receptors are protons (it’s like having little pH meters in our mouths). The more acidic something is the more sour it will taste.

Bases on the other hand tend to taste soapy and they also tend to trigger bitter receptors, the receptors that are often trying to suggest that we shouldn’t eat a particular food. Almost all of our food is acidic rather than basic so it’s likely we’ve evolved to prefer acidic foods more than basic compounds. This is why we tend to use acids rather than bases in our cooking. If we used bases our food would taste pretty bad. When we do use bases in cooking it tends to be for a specific chemical reaction. For example, when we use baking soda (NaHCO3 or sodium bicarbonate) in bread we are counting on it reacting with an acidic ingredient, buttermilk for example, to produce carbon dioxide that will leaven the dough and expand when it cooks in the oven.

Every chef in the world knows that one of the secrets to making restaurant food taste better than home food is to use an appropriate amount of acid. We all probably under use acid in our home cooking and we can add some pizzazz to our home cooking by using it more. Acids balance out richness, they activate our palate by stimulating saliva production and they counter sweetness and bitterness making for a more balanced dish. Personally, using acids in my cooking was a bit of a revelation so I’m a convert to seasoning with lemon juice, vinegar or whatever nice tasting acid I can find (verjuice, a highly acidic juice made from unripe grapes, is another one). All this is starting to get into the art of cooking which I’m not competent to advise on so I’ll leave it here, hopefully where we all have a better understanding of how acids and bases can help us in our cooking and in the disposal of inconvenient corpses.

Footnotes

- This type of acid is known as an Arrhenius acid. Broader definitions of an acid include a Brønsted-Lowry acid, which can donate a proton to another compound, and a Lewis acid, which is a compound that can accept a pair of electrons. We don’t really need to worry about the two broader definitions though if you read the post on oxidation/reduction reactions you’ll recognise the Lewis acids can be quite important in those chemical reactions. ↩︎

- In this formula I’m depicting the liberated proton as the hydronium ion which is the stable form of protons in water. We don’t need to worry about that too much but you’ll commonly see it when acids are being discussed so it’s worth knowing if you want to do more reading. ↩︎

- Formally the pH of a solution is the negative log of the H+ concentration. In equation form it is ‘pH = −log[H+]’ where [H+] is the molar concentration of the protons. We don’t really need to worry about this too much except to realise the low pH means acidic and high pH means basic. ↩︎

- The theory behind the pH scale is probably a bit more than we need but a quick explanation involves the the fact that water itself is both an acid and a base. In pure water a very small amount of water will dissociate into a proton and a hydroxide ion. At a given temperature there will be a small amount of each and their concentration will also be equal (because water is just a proton and a hydroxide ion). The equilibrium constant for this reaction is called the ion product of water (Kw) and at 25C it is 1.0 x 10-14. What this is saying is that the concentration of protons times the concentration of hydroxide ions will always equal 1.0 x 10-14 so if you add an acid and the proton concentration goes up then the concentration of hydroxide ions will decrease. You can see from this that the pOH is just the inverse of the pH, and vice versa, and at pH7 the proton concentration and the hydroxide ion concentration are the same. ↩︎

- OK, I’m sorry. I’ve tried to keep the discussion limited to Arrhenius acids and bases, i.e. compounds that increase the proton or hydroxide ion concentrations. But the basic amino acids are all Brønsted-Lowry bases, that is they don’t dissociate into hydroxide ions but they accept a proton. By taking a proton from water they leave behind a hydroxide ion which is why they increase the pH. Arrhenius was working in the late 19th century and we didn’t know a lot about proteins then, or acids and bases for that matter. ↩︎

- The pH at which a molecule, a protein or an amino acid for example, has a net neutral charge. ↩︎

- We are mostly talking about ionic bonds here but hydrogen bonds are also very important in protein folding and they are also disrupted by free protons and hydroxide ions. ↩︎

- Though it is significantly more acidic at higher concentrations because of a process called homoassociation. At higher concentrations HF molecules cluster together to form polyatomic ions like the bifluoride ion (HF2–) and protons. The complications with acids and bases never stop! ↩︎

- The type of bond is a chelation where two or more separate bonds form between a ligand, F– in this case, and a single metal atom (yes calcium is a metal). So HF chelates calcium and magnesium. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Gary Cancel reply