I’ve been catching up on the latest series of the Great British Bake Off and in one episode, amongst all the usual drama of collapsing pastries and sagging cakes, the contestants were overcooking their caramel for the Banoffee Pie technical and it made me think about sugar. In recent posts I’ve talked a lot about dissolving things but it’s mostly been in the context of things that don’t want to be dissolved. Making emulsions with oil and water for example or hydrophobic interactions between proteins in pasta. Sugar is the opposite, sugar dissolves very easily in water. You can easily dissolve up to two parts of sugar in one part water, at room temperature no less. But what makes sugar even more interesting is that a simple mixture of sugar and water has incredible versatility. With this simple mixture you can construct a dizzying array of sauces and confectionery and the ability to do this all comes down to what happens when you apply heat to a sugar solution and then let it cool down. When you do this you can end up with a simple syrup for some ice cream, a caramel for a Banoffee Pie or a hard toffee draped over an apple.

Now sugar is a huge topic and I’m not going to cover it all in this blog post. The human dependency on sugar, the way we have evolved to crave sugar and that the modern world, awash with sugar, is probably not that great for our health are all things that will have to wait for future posts. I’m going to take it for granted that we all know we shouldn’t eat too much sugar and that we need to brush our teeth if, surprise surprise, we do snack on some sugar rich food on cheat day. What I do want to do is introduce sugars at a chemical level and have a look at why something as apparently simple as a syrup can be so versatile. As part of this we will also need to develop an understanding of crystallisation, which is, for our purposes, the transformation of dissolved sugar into crystals at certain concentrations and temperatures. Mostly the science behind sugar cookery is the science of crystallisation and most sugar cookery boils down to preventing or controlling the size of the crystals that we allow to form in our syrups.

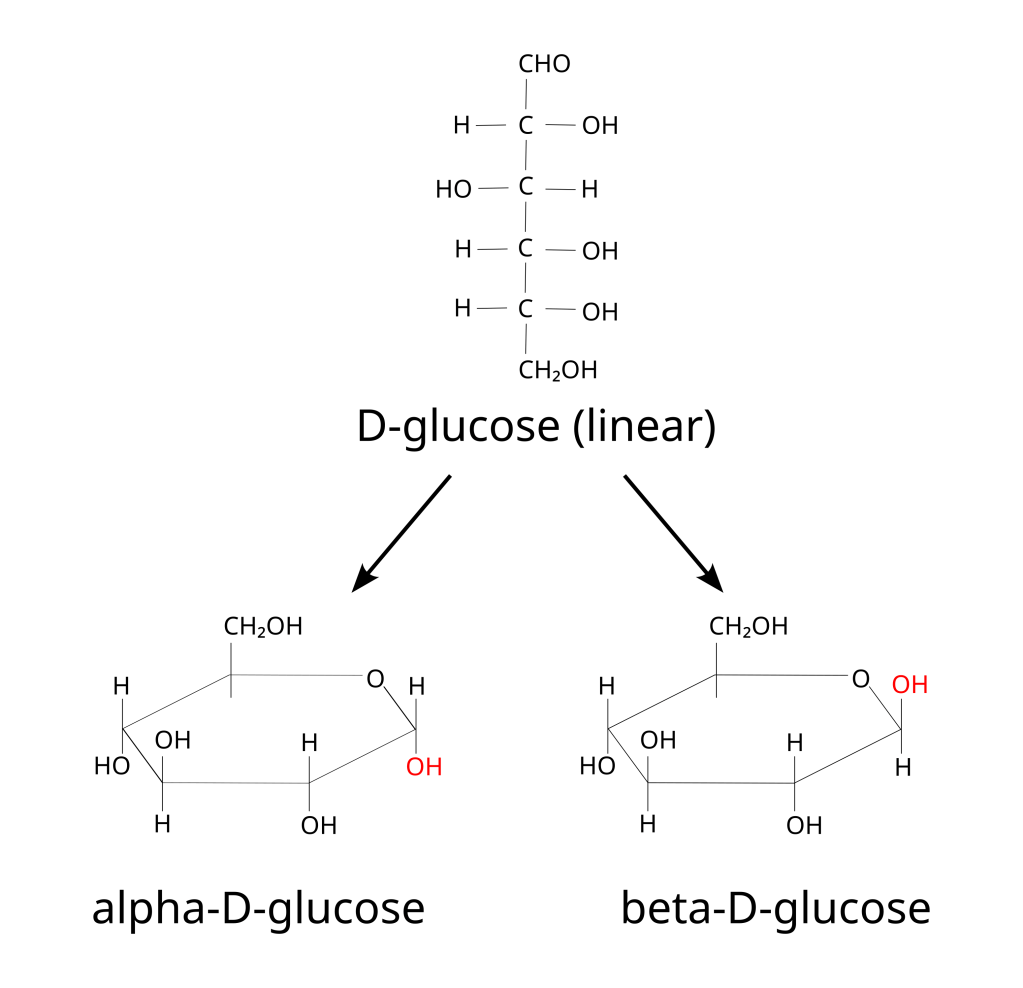

So lets start with the chemistry of sugar. The chemical definition of sugars is that they are molecules made of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) in the ratio (in chemistry called the stoichometry) of Cx(H2O)y. In biochemistry we normally refer to sugars as carbohydrates which means ‘watered carbon’ and this refers to this definition where we have some number of water molecules (H2O) for each carbon atom in the molecule. It’s a pretty loose definition, some sugars don’t precisely match this description and other molecules that do aren’t actually sugars so don’t be confused if you come across sugars that don’t have this exact stoichiometry. In the kitchen we mostly deal with common well-known sugars so it wont be much of an issue for us.

Carbohydrates are commonly divided into four broad groups according to their size. The first group, monosaccharides, are the basic building blocks of carbohydrates. They are single sugar molecules and common monosaccharides include glucose, fructose and galactose. Monosaccharides can combine with each other to form larger more complex carbohydrates and these are roughly categorised based on the number of monosaccharides they contain. A disaccharide is formed by two monosaccharides and these include things like sucrose, common table sugar, which is formed by one glucose and one fructose molecule, lactose, the sugar found in milk, which is formed by one glucose and one galactose molecule and maltose, which we normally encounter in corn syrup, which is formed by two glucose molecules. What we commonly refer to as sugar are either monosaccharides or disaccharides.

More complex carbohydrates are not generally called sugars but they are also important and we have come across some of them before. Oligosaccharides, combining three to ten monosaccharides, are often found attached to lipids or amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) and when attached to amino acids they are often the cause of Maillard reactions that make for a nice sear on a steak. Polysaccharides, any carbohydrate made from more than ten monosaccharides, are generally structural or storage molecules, one important example being starch which we have seen before as an important actor in the french fry story. Other important polysaccharides include glycogen, the primary energy storage molecule in humans, and cellulose, the major structural component of plant cell walls.

Now that we’ve got all that chemistry out the way lets look at what happens when you put sugar into water. We already know that sucrose dissolves really well in water and, if you read my post on emulsions, you can see why from the chemical structures of glucose and sucrose. All those hydroxyl groups (the OHs) in sugar molecules can form hydrogen bonds with water molecules that surround the sugar and prevent it from interacting with other sugar molecules. So when we add solid sugar crystals to water, over time, sucrose molecules will gradually stop interacting with other sucrose molecules and will instead be surrounded by the more numerous water molecules in process that we call hydration.

The ability of water to hydrate sugar relies on there being enough water molecules to surround every sugar molecule and prevent the sugar from interacting with other sugar molecules. If we continue adding sugar more and more water molecules will be needed to hydrate the additional sugar and eventually we’ll get to a point where all of the water molecules are hydrating sugar molecules and there are no more water molecules left to hydrate more sugar. When the solution gets to this point we call it a saturated solution, the amount of water in the solution can not hydrate any more sugar. If you add more sugar it will just stay in it’s crystalline form. This just doesn’t apply to sugar and water, any molecule that is soluble in a solvent will show the same behaviour, the solubility of any substance is the amount of that substance that you can dissolve in a solvent at a given temperature.

There are complications though. Notice that I just mentioned temperature. An important thing about solubility is that it is temperature dependent. Generally, if you increase the temperature you increase the ability of a solvent to dissolve another substance. This is certainly the case with sugar and water. So say we heat some water to some temperature and then add enough sugar to saturate the solution, the sugar will dissolve and everything is good. If we then remove the solution from the heat and let it cool we will have more sugar dissolved in the water than the water is capable of hydrating, when this occurs we call the solution super-saturated. As you would expect this state of affairs is not ideal from a free energy perspective and so this is where we need to start thinking about crystallisation. Because if a supersaturated sugar solution is disturbed the sugar will begin to crystallise out of the solution until the solution achieves an equilibrium between the uncrystallised sugar and the water available to hydrate it.

So what are crystals and what is crystallisation? A crystal just describes a solid in which the molecules are arranged into a regular, repeated pattern. And when something is crystallising in solution it just means that it’s molecules are interacting with each other and naturally forming a crystalline solid. Many things form crystals, salt and sugar are common in the kitchen, and compounds that do crystallise will begin to crystallise in a super-saturated solution. If a substance doesn’t form crystals then they wont crystallise but for these compounds precipitation is a similar process but I’m not going into that now.

For chemists crystallisation is a crucially important technique, primarily as a way of purifying compounds from mixtures containing impurities. I’m really simplifying things, but by heating a mixture, and evaporating the solvent, you can force the concentration of your compound above its saturation point and obtain pure crystals once the mixture is cooled. Crystallisation is used to purify chemicals in research laboratories and during chemical, pharmaceutical and food production. Sugar and salt are both purified using crystallisation and if you’ve watched Breaking Bad then you’d recognise crystallisation as what Walter White was using to purify his compound of interest. But, although chemists are usually trying to make crystals, for anyone working with sugar the opposite is true. In general cooks either want to stop their sugar crystallising at all or want to ensure small very fine crystals. In confectionery crystals generally mean graininess and the larger the crystals the worse the graininess.

Now when we are making syrup or caramel we don’t calculate the solubility of sugar and add enough to saturate the solution. What we do is bang some sugar into water and start heating it. If we are making a simple syrup we just wait till the sugar is dissolved and take it off. We don’t need to worry about crystallisation because we haven’t saturated or super-saturated our solution we’ve just used the heat to make it dissolve faster1. But what if we continue to heat our sugar solution, what happens then? Well we all know that if we boil water it starts to evaporate and as the water evaporates from our syrup the sugar becomes more concentrated. The boiling point of a sugar solution increases as the concentration of sugar increases so we start to get well over 100C/212F and our water continues to boil off which increases the concentration again and so the temperature increases again. This is why you can lose control of your caramel really quickly, the rate of the temperature increase increases so things can get very hot very quickly and you can go from a pale caramel to burnt in no time.

We can stop this process at any time and the amount of water that is left in the solution dictates how runny our cooled syrup/caramel/hard candy will be and thus what we can use it for (there is actually a nomenclature about this but I didn’t have the space for it, if you are interested see here) . But we may also have a supersaturated solution and once we start cooling we want to be able to control the crystallisation and the most important things to know about crystal formation is that they need a nucleation site to begin forming, that higher temperatures produce bigger crystals2 and that stirring reduces the size of crystals3. So when we are cooling our solution we want to either not allow any nucleation sites at all or only allow them once our solution has cooled to a temperature that will give us crystals of our desired size and then stir vigorously. This is why when making fudge you let your syrup cool down before initiating crystallisation by stirring and continuing to stir until it’s cooled down and no longer workable.

I kind of brushed over nucleation sites but in technical terms a nucleation site is a place where a substance can start to undergo a phase shift. In our case it’s a place where sugar can come out of solution and become a solid crystal. Nucleation sites can be microscopic scratches in pots or pans, dust particles, tiny air bubbles, tiny crystals formed from splatters onto the side of the pan that are stirred back in, metal spoons can conduct heat away from local parts of the solution making them supersaturated and even just agitation or stirring can encourage crystallisation by knocking the sugar molecules together. What this means from a practical standpoint is that when we are cooling our syrup down we want to avoid agitating the solution, wipe away any dried sugar from the side of the pan and stirring implements and use a wooden spoon4.

We’ve only really only talked about sugar/water solutions but typically confectionery can have a lot of different things added and a lot of these additives can also help prevent crystallisation. Traditionally, you would add glucose and/or fructose which interact with sucrose blocking other sucrose molecules from crystal formation. Honey was probably the first thing to be used this way but in modern times corn syrup is generally added to prevent crystallisation, which is why you’ll see more than a few fudge recipes using corn syrup on the internet. Likewise, milk and cream with their rich cargoes of fat and protein will tend to reduce sucrose crystallisation and because they are added while the syrup is still hot Maillard reactions will occur between the sugars and the milk proteins. This not only stops excessive crystallisation but also adds some delicious Maillard flavours. Think caramel sauce for example where the sweetness of the sugar is combined with Maillard flavours and the mouth-feel of milk fats.

Finally, the other thing that is happening at high temperature is the breakdown of sugar itself. When you get to 165C/340C your solution will be almost 99% sugar and the sugar itself will start to break down and caramelise. So things like toffees and caramels will be coloured and have a distinctive flavour because of the new molecules that are being formed by the breakdown of the sucrose molecules. This is similar to the Maillard reaction but, unlike when you ‘caramelise’ your steak, this is true caramelisation which is a sugar only event. The browning you get from the Maillard reaction depends on the interaction of proteins and sugars (specifically reducing sugars which are monosaccharides with a free hydroxyl group that can donate electrons). So saying you are caramelising your steak is probably the wrong thing to say. Maillarding your steak?

As per usual I’ve barely scraped the surface and there is plenty more science that is applicable to confectionery. But understanding how sugar and water interact, how super-saturating solutions are formed and why they can cause crystallisation is a solid first step into the science of sugar.

Footnotes

- In fact you don’t need to heat a syrup at all, you can make a syrup by just putting some sugar into water and letting it sit for a while. A 1:1 mixture of sugar to water will take about 15-20 minutes to dissolve whereas a 2:1 mixture will take about 45 minutes (Serious Eats has a good article about it). The downside is that if you are going to store your syrup and you don’t heat it you can end up with a syrup that rapidly spoils. ↩︎

- Bigger crystals form at higher temperature because the sugar molecules are moving rapidly and are more likely to run into each other and get added to a crystal. At the same time crystals will be less stable because they are being bashed together. So at high temperatures you’ll have less crystals surviving but once established they will grow quickly and form larger crystals. ↩︎

- As you stir you are agitating the solution and encouraging sugar molecules to knock into each other. So the more you stir the more collisions you will cause and the more crystals will form. If you stop stirring the existing crystals will tend to grow larger rather than more smaller crystals forming. ↩︎

- If you make coffee in a microwave you should be aware of a similar thing that can happen when heating coffee in a microwave. Because the microwave acts directly on the water molecules you don’t get water bubbles forming on the surface of the container and if the container is smooth, like glass, you wont have any nucleation sites for the water to change phase to a gas. So a coffee can become superheated in the microwave where it is above boiling temperature but there is no bubbling. If you take it out of the microwave and stir it will start boiling quickly and explosively. You can be seriously burnt from superheated coffee. It’s not just coffee either any aqueous solution in the microwave can behave this way and anyone who has worked in a molecular biology lab would also be familiar with this if they ever made agar. ↩︎

Leave a comment