Emulsions where would be without them? No mayonnaise, no custard, no hollandaise and no milk, butter or sausages. Not having thought too much about it before, I was surprised to find out just how many of my favourite foods are emulsions or how many are covered with emulsions when I eat them. It’s pretty clear that if you want to be able to liven up your salads with a quick vinaigrette, make some aioli to go with your home made fries or impress dinner guests with a salmon foam then emulsions should be an important part of your cooking repertoire.

From a scientific perspective emulsions are really interesting. An emulsion is basically a mixture of two things that really do not want to be mixed. You need to put energy into your emulsion to get it mixed and once formed it is not an energetically stable mixture and needs to be stabilised. In making an emulsion you are defying the second law of thermodynamics and the science behind creating and stabilising emulsions can get a bit hairy. Given this, instead of dumping it all out there at once I thought we would start with the simplest of emulsions: the vinaigrette. In it’s simplest form a vinaigrette is just a mixture of oil and water, the water usually taking the form of an acid, such as vinegar or lemon juice.

Now I’m not saying that vinaigrettes are the most interesting thing in the world. A vinaigrette is what I put on lettuce to make it taste like something other than lettuce. But it is a good place to start before we head off to more complicated, and more delicious, things like creme anglaise, mayonnaise or hollandaise. In these types of emulsions splitting is a constant source of anxiety and heat can render your emulsion into scrambled eggs faster than you can say bacon and egg ice cream. But when making a vinaigrette there is almost nothing that can go wrong and yet the science behind it is involved enough that when we come to more complicated emulsions we will be well prepared.

As I said, an emulsion is a mixture of two substances that don’t want to mix. What drives this reluctance to get together is the concept of hydrophobicity. If you read the post on pasta I went through the concept of hydrophobicity and simply put molecules that don’t have a partial electrical charge on their surface don’t like interacting with water, they prefer to hang out with other uncharged things. So in water hydrophobic molecules will clump together to minimise their contact with water. To understand emulsions we need to refine this idea a bit more. But before we get to that lets start by considering what an emulsion is not.

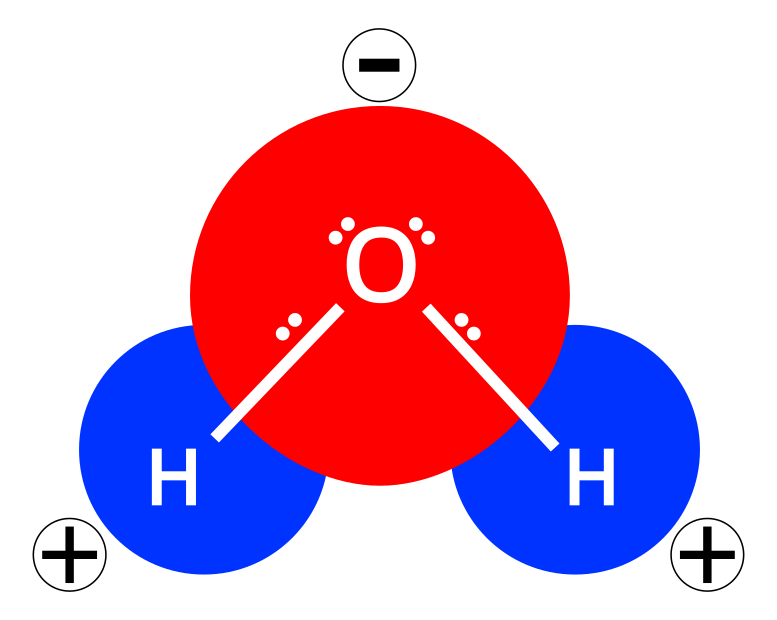

Water is an interesting molecule. Water is polar, it has a slightly positive end and a slightly negative end, kind of like a battery. It has these partial charges because the oxygen and hydrogen atoms in water share electrons and the oxygen atom hugs these electrons a little closer to itself than the hydrogen atoms are able to. So the oxygen is a little bit negative and the hydrogens are a little bit positive. Because of it’s polarity, water is really good at interacting with things that are also polar, including itself. Pure water forms a matrix in which opposite charges on different water molecules are interacting, these interactions between the partially charged hydrogen atoms and partially charged oxygen atoms are called hydrogen bonds. Salt and sugar are easily incorporated into this matrix because they are also polar substances and the negative and positive charges on these molecules interact happily with the opposite charges found on the water molecule.

Salt, for example, is just a sodium cation (ions are charged molecules or atoms and a cation is a positive ion) and a chlorine anion (anion is a negative ion). When you mix salt and water the polar nature of water means it will spontaneously form electrostatic bonds with the sodium and chlorine. Once this has happened the salt is dissolved in the water and you can’t easily get your salt back out (without crystallising it or something). In technical terms the salt is now a solute and the water is a solvent and both of them together are a solution. Sugar, carbon dioxide and a whole bunch of other things dissolve in water like this, but some things don’t.

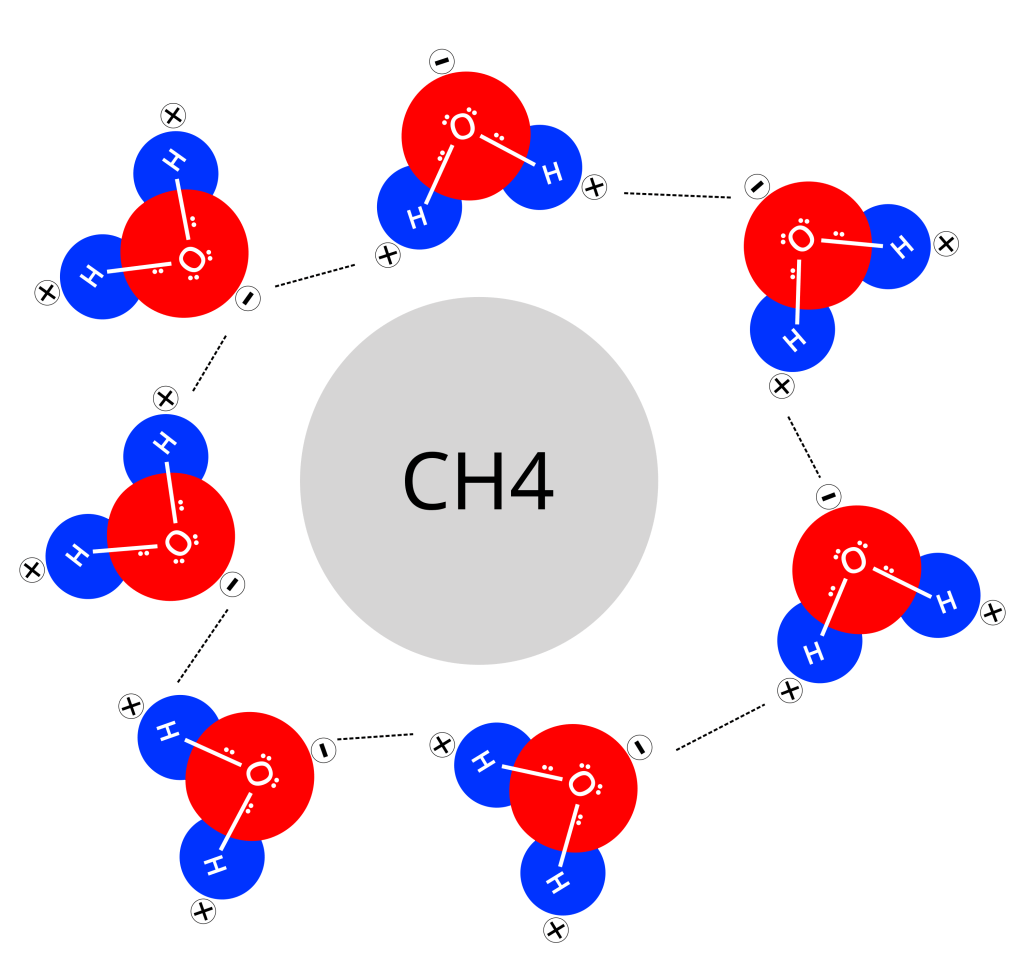

Things that aren’t polar do not spontaneously dissolve into water like polar solutes. When you add oil, a non-polar molecule, to water they don’t mix. If you add oil to water and leave it alone the mixture will arrange itself to minimise the surface area between the oil and the water. In practical terms this means that, in the presence of gravity, the oil will form a layer on top of the water. With the exception of foams, almost all the emulsions you come across in the kitchen are a mixture of oil (or fat which is just an oil that is solid at room temperature) and water. So to make our emulsion we need to add energy to break the bonds between water molecules and ‘force’ our non-polar molecules in amongst the water. For our vinaigrette we add this energy by shaking or vigorously whisking the oil and the water together.

Once mixed, in the absence of a stabilising force, the oil and water will begin to spontaneously separate. Eventually we’ll end up right back where we started with the oil floating in a single layer on top of the water. What is happening here is that the oil and water emulsion is moving back to it’s lower energy state. We put energy into the system by mixing and, without any stabilising force, that energy will gradually dissipate and the oil and water will separate again. In thermodynamics terms, our mixture is following the second law of thermodynamics by tending towards the state with the lowest free energy (if you are interested in this I describe all this in terms of free energy using my pigeon physics below).

Now you may say, what about mayonnaise? Mayonnaise is an emulsion and it seems pretty stable. Whats going on there? In most of the emulsions we make in the kitchen what we end up with is a mixture of tiny droplets of oil dispersed in water. We call this kind of emulsion an oil-in-water emulsion and we say that water is the continuous phase and oil is the dispersed phase. The more droplets of oil you get dispersed throughout the watery continuous phase the thicker and stiffer your emulsion will be, just like mayonnaise for example. If there are less droplets of oil then the mixture will be runnier, more like a custard or hollandaise. To make these kinds of emulsions you need the help of emulsifiers. I’ll talk much more about these molecules in later posts, but for now it is enough to know that emulsifiers make it easier to form an emulsion and will then stabilise it after it has formed. Using emulsifiers you can get up to three parts of oil dispersed into one part of water.

Vinaigrettes are a little different. The usual ratio of oil to acid is also two or three parts oil to one part acid. But without emulsifiers there is no way you are going to get that much oil into the dispersed phase and so the whole thing is flipped and vinaigrette becomes a water-in-oil emulsion. The water is the dispersed phase and it forms droplets in the oil. With much less dispersed phase the emulsion that forms is pretty runny when compared to something like mayonnaise. But this is ideal for the usual application of a vinaigrette as the dressing for a salad. The runny vinaigrette is better able to coat the relatively large surface area of the salad than a thicker, creamier oil-in-water emulsion.

In it’s purest form of just oil and vinegar, your vinaigrette is going to eventually split and separate into oil and vinegar again. Really this isn’t much of problem, most of the time you make a vinaigrette and put it straight on the food you are saucing. But you can do a few things to stabilise your vinaigrette a bit. Firstly, and this applies to all emulsions, you can stabilise an emulsion by generating smaller droplets in the dispersed phase. Larger droplets will split quicker as when they collide and coalesce each collision represents a larger proportion of the dispersed phase. Larger droplets will also rise to the surface (or drop to the bottom if water is the dispersed phase) of the emulsion more quickly, also hastening coalescence. There are a few things you can do to get smaller droplets in your vinaigrette but using a blender to mix the emulsion is probably the easiest.

As I mentioned above emulsifiers can stabilise an emulsion. And there are plenty of aromatics that contain emulsifiers that can be added to a vinaigrette. Both mustard and garlic, for example, contain emulsifiers that will stabilise your vinaigrette and stop it from splitting as quickly as it would without them. My favourite vinaigrette, because it goes on steak, is chimichurri. Chimichurri is a heavily herbed vinaigrette of olive oil and vinegar with minced garlic added as an aromatic but which also contains emulsifiers.

Of course, if your vinaigrette splits all you need to do is shake it again to reform the emulsion. So I wouldn’t get too concerned with stabilising a vinaigrette, particularly if it’s going to change the flavour profile you’re aiming for. Also if you add enough emulsifiers you’ll end up with an oil-in-water emulsion, like mayonnaise, which may not be a texture you are looking for.

What I haven’t talked about much here is flavour. A vinaigrette is really all about getting some fatty luxuriousness contrasted with some type of acid and flavoured with some aromatics. You can make vinaigrettes with any type of oil or fat; bacon fat, olive oil and neutral oils will all taste different. There are a multitude of acids that you can use, red vinegar, malt vinegar, lemon and lime juice and verjuice are all good options. And the aromatics you can add are legion, all the herbs of the world, garlic, shallots, chillies and spices. The only real problem with vinaigrettes is option paralysis. There is a science of flavour but I’m not going to get into that incredibly complex topic here, for now experiment and see what you like.

That’s it for vinaigrettes. For something that is just a mixture of oil and water there is an awful lot of science going on (especially so if you read the the discussion below). But it’s also science that we will revisit when we come to things like mayonnaise, hollandaise and custards. We have completely ignored the effects of temperature on our emulsions and have barely touched on important topics like emulsifiers. We will get onto these topics but understanding the rich science behind a thing as simple as a vinaigrette will hold us in good stead when get there.

Other stuff

Gibbs free energy and solubility

I’ve tried to keep the discussion above reasonably free of physics but emulsions are pretty good examples of free energy and the second law of thermodynamics. If you aren’t interested in this skip it, the explanation above will still work for future posts, but if you want to go a bit deeper read on. It’s really only high school level physics, which is just as well as I’m not a physicist.

The solubility, or not, of a molecule in water can be described in terms of the changes in Gibbs free energy between its undissolved and dissolved states. Gibbs free energy describes the thermodynamic potential of a system. The formula for the difference in free energy of two different states goes as follows:

dG = dH – TdS

Where delta G (dG) is the change in Gibbs free energy, delta H (dH) is the change in enthalpy, T is temperature and delta S (dS) is the change in entropy. Enthalpy can be thought of as the internal energy of the system. Entropy can be a bit harder to grasp, but I just think of it as the number of potential microstates there are in a given system. For example, if you increase the heat of a solution you increase the movement of molecules in the solution which increases the entropy because the increased ‘range’ of the molecules provide more potential states for the system to be in. Likewise conformational constraints on molecules can also cause a decrease in entropy, like if you freeze water.

Gibbs free energy is important because for any reaction to be spontaneous the new state of the system needs to have a Gibbs free energy that is smaller than the original state. That is the dG going from the first state to the second needs to be negative. The reaction will be spontaneous because the second law of thermodynamics tells us that things will tend to move towards a state that minimises free energy. The second law also forbids spontaneous movement from a state with a lower free energy to one with a higher free energy. So anything that dissolves spontaneously in water must have less free energy in it’s dissolved state than it’s undissolved state.

Lets consider something like calcium chloride (CaCl2). Breaking a bond requires energy (it is endothermic) and forming a bond releases energy (it is exothermic). When calcium chloride dissolves in water a bunch of bonds are broken and a new bunch of bonds are formed. For calcium chloride the sum of the energy fluctuations during all this bond breaking and reforming is negative (the precise value is −80 kJ/mol at 27C). This means that when calcium chloride dissolves energy is released and the solution containing it becomes a little warmer. This is the enthalpy part of the free energy equation, so in this case the value of the dH term will be negative.

The complex of water with the calcium and chlorine is more structured than that of the of undissolved crystal so we actually get a negative entropy value for the reaction (-44.7JK-1) but the heat produced by the enthalpy of the reaction also increases the entropy of the solution so the dS term ends up only slightly negative. So overall dG ends up negative and we get the spontaneous dissolution of calcium chloride in water.

Salt, a complex of Na+ and Cl–, is interesting. We all know that salt spontaneously dissolves in water but the enthalpy of this reaction (dH) is actually positive. The reason that salt will dissolve in water at all is that there is an increase in entropy that outweighs the positive enthalpy term. The dissolution of the two ions of salt and the relatively unstructured complex they form with water increases the number of microstates in the solution so the entropy has increased enough to cancel out the positive dH. This means that salt dissolving in water is an entropy driven process. When you put salt in water it will spontaneously dissolve (overall dG is negative) but because the enthalpy is positive it will actually cause a drop in temperature of the water because it needs thermal energy from the water to power the reaction.

If salt and calcium chloride will spontaneously dissolve in water because the free energy change is negative then the reverse, salt and calcium chloride coming out of solution under the same conditions of temperature and pressure, will have a positive dG. So this will not happen unless conditions are somehow changed. We can now define a solution as a mixture of water and a solvent that has a negative free energy of dissolution in water.

Now lets look at an oil or fat. To get an oil to mix with water we need to break bonds between water molecules but, because the oil is non-polar, no new bonds are formed. This means we’ll have a positive enthalpy (dH). In plain speech, to break the bonds binding water molecules to other water molecules energy is required but we aren’t releasing any energy by forming new bonds to compensate so we just end needing energy. We will also have a decrease in entropy (dS) as water forms a ‘cage’ around non-polar molecules (called a clathrate1) that restricts the movement of water molecules and the oil molecules are also constrained and can’t move around as freely as the would in the separated state.

A positive dH and a negative dS means we end up with a very positive dG for a non-polar molecule to dissolve in water. So it wont happen unless we force it to happen by adding energy. Shaking or whisking the mixture does this nicely. Conversely, once mixed the dG for moving to the separated state will be very negative meaning that, unless stabilised, our emulsion will spontaneously split as it moves towards a state with a lower free energy. It’s the second law of thermodynamics in action.

Footnotes

- OK – I know I haven’t included the hydrogen bonds between water molecules forming the clathrate when considering the enthalpy, but this post is already way too long. Also people are still publishing papers trying to work out the details of the hydrophobic effect so I’m leaving it like this for now. ↩︎

Leave a comment