Does any other dish transcend it’s ingredients in quite the same way as french fries? Just by dipping into blazing hot oil the humble potato is transformed into the golden, crunchy delight known as a french fry (or if you are in the UK or Australia a ‘chip’). The chip, yes I’m Australian, is something more than just a strip of cooked potato. As anyone under ten will tell you, roasted potatoes are still potatoes but fries are fries.

We’ve all had our share of soggy or leathery fries, but for the most part restaurants and fast food joints do a pretty good job with fries. The real problem is how do you make them yourself in your own kitchen. Without heavy duty kitchen equipment, like deep fryers and water bathes, it seems almost impossible to achieve that golden crunchy goodness without dedicating an entire day to the process. But I’m a scientist, I thought to myself, and I’m sure that science can tell us something about the humble yet magnificent chip and how to achieve a halfway decent home fry?

So I started to research and, to be honest, I was almost scared away from writing on this topic altogether. I’m not the first person to embark on the quest to achieve a decent home chip and the subject has received a lot of attention. Among the usual multitude of sites with the ‘best’ way of making french fries, reputable sources like J. Kenji López-Alt has gone into exquisite detail in his book and blog. I didn’t know exactly what more I could contribute. But the science is interesting and has other applications, especially to that other great potato dish, mashed potatoes (which I’ll cover in a future post). I also haven’t done much vegetable science on the blog yet so I pressed on and learn’t more about frying a strip of potato than I ever thought I would know. In this post I’ll describe the literal tip of the iceberg when it comes to making fries but hopefully at the end we’ll all be a little bit smarter when reading about and attempting to make home-made fries.

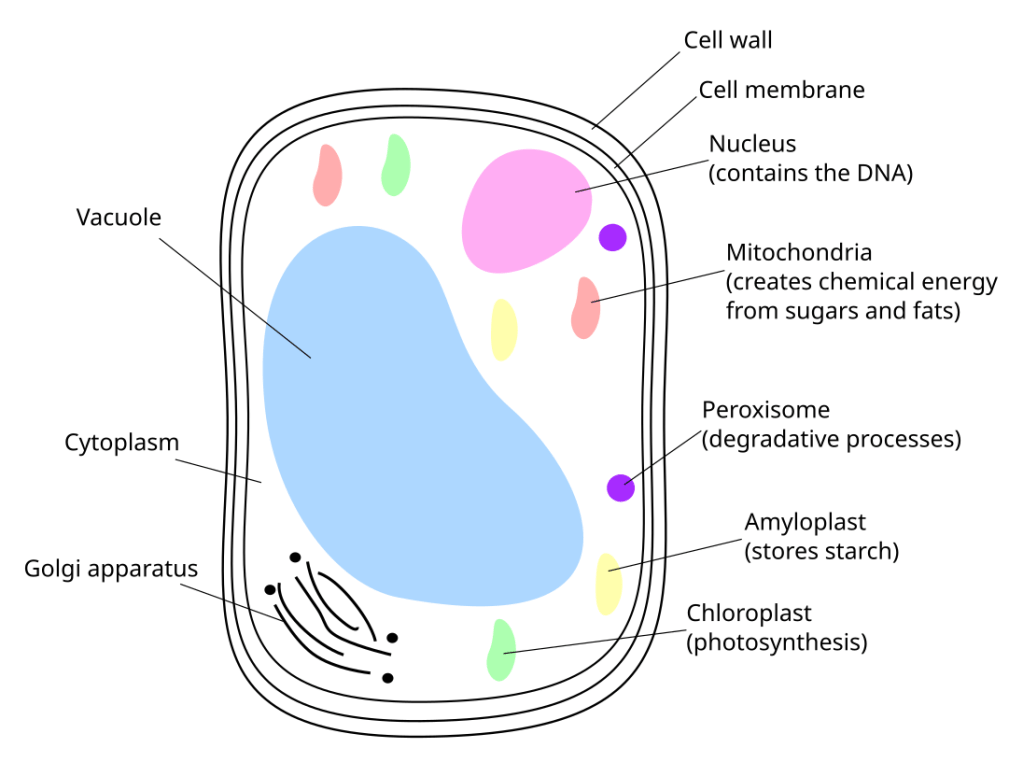

We need to start with potatoes. Potatoes are an example of a tuber. Tubers are storage structures that develop from the stem or the root of a plant (see the vegetable quick bite for a quick primer on plants from a cooks perspective). Tubers are capable of developing into whole new clone of the parent plant. Something we’ve all seen in potatoes that have begun to sprout when left too long in the cupboard. To fuel the new plant potatoes are absolutely stuffed with starch, the source of energy for the developing plant. As we’ll see this starch is crucial to our quest for homemade fries. We also need to know about plant cell walls. Each cell in the potato, and all other plants as well, is surrounded by a durable but flexible cell wall (I go into this more in the vegetable quick bite). For our future chip, the cell walls of the cells towards the surface of the chip will contribute to the crunchy exterior of our fry.

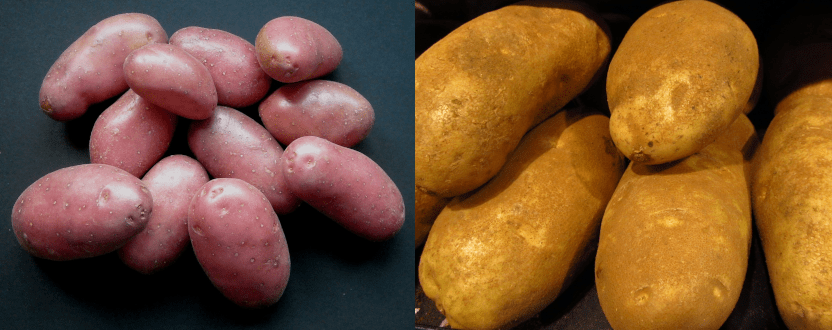

One of the most important steps in cooking good fries is picking the right type of potato. There are about 200 species of potato but they can be divided into two broad groups: waxy potatoes and ‘mealy’ or starchy potatoes. You can probably guess that starchy potatoes have more starch in their cells than waxy potatoes. But crucially the starch composition is different. Waxy potatoes have starch that is almost entirely made up of a sugar called amylopectin while starchy potatoes is made up of amylopectin but also a smaller sugar called amylose. For a good french fry it is absolutely essential that you choose a starchy potato with it’s comparative abundance of it’s amylose enriched starch.

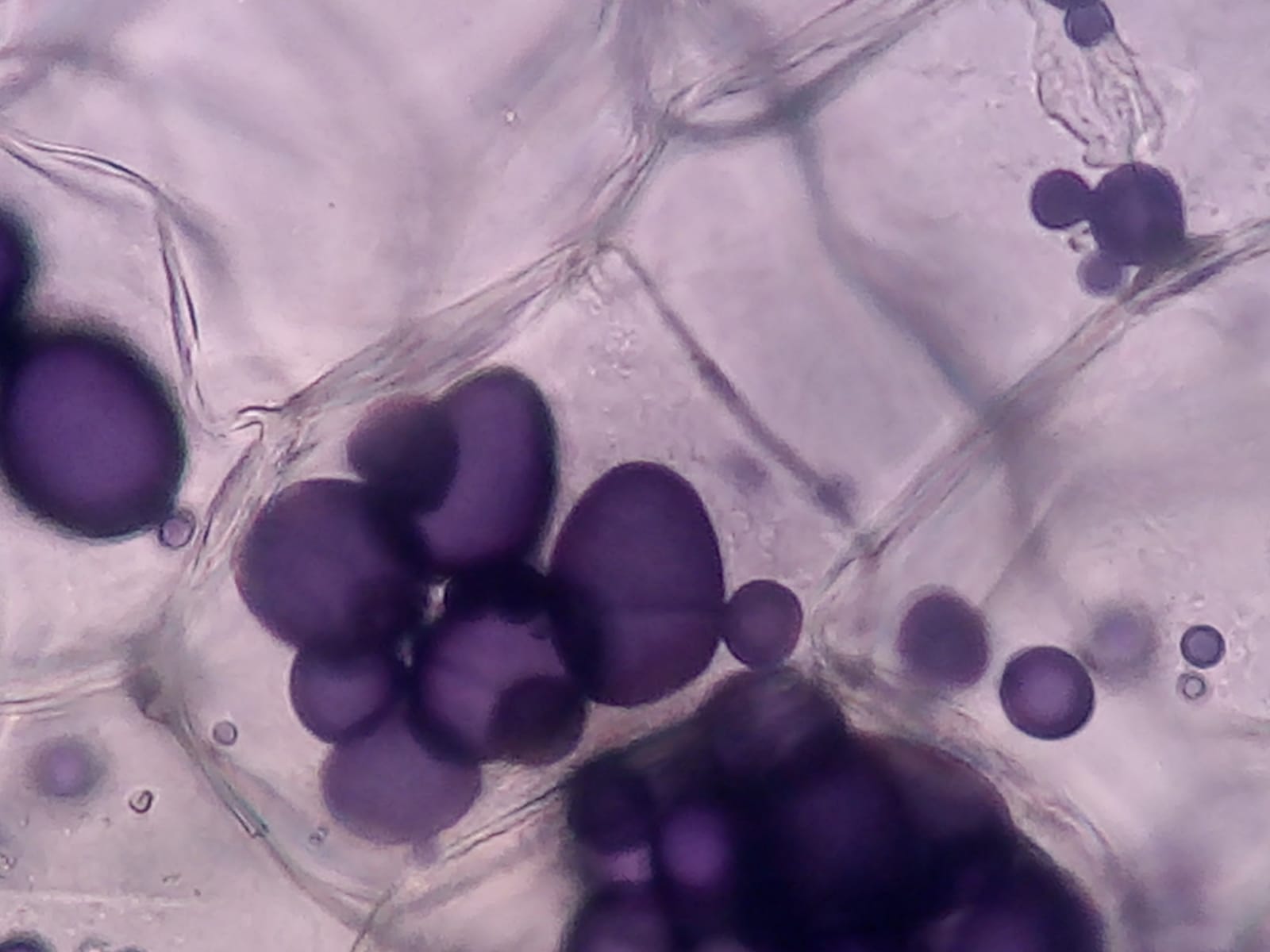

The reason why the starchy potato is so essential comes down to what happens to starch when cooked in the presence of water. The basic structural unit of starch is called a granule. When starch is heated the granules begin to absorb water and swell up. This water can come from inside the cell, for example when frying, or outside, if they are being boiled. As heating continues the granules will burst producing a thick paste in a process called gelatinisation. Gelatinisation is also the reason we put flour into stews and sauces, the starch in the flour gelatinises and thickens a runny liquid. Importantly, starch from starchy potatoes gelatinises at around 58C/136F while starch from waxy potatoes doesn’t start gelatinising until 70C/158F. So starchy potatoes not only contain more starch but it is a type of starch that gelatinises at much lower temperature than that found in waxy potatoes.

The upshot of this is that when we cook potatoes, starchy varieties will have cells that are almost completely filled with gelatinised starch. Waxy potatoes will have cells composed of only 30-50% starch granules with more free water. This is why waxy potatoes seem wetter when eaten. When waxy potatoes are ruptured during chewing the cells release water. Starchy potatoes have almost no free water, all the water is bound up in starch granules, so when we chew them no free water is released. This also makes starchy potatoes good for fries as there wont be any residual free water in the fry that can make the chip go soggy, the water is bound up in starch granules.

As we saw above, all plant cells have walls in addition to the cell membrane. This wall is made up of fibres of cellulose held together in a matrix, or cement, primarily made up of another polysaccharide called pectin (see the vegetable quick bite for more on this). When cooked, the cell walls of starchy potatoes experience more pressure than waxy potatoes as the swollen starch granules push against the cell membrane and cell wall. As a consequence the cells in starchy potatoes tend to separate from one another while cells in waxy potatoes, under less pressure from swollen starch granules, tend to stay together. So waxy potatoes hold their structure better than starchy potatoes. This makes waxy potatoes good for salads and other dishes where you want a potato with a bit of structure. Starchy potatoes are good for things like mash where you want the cells to separate and get coated in things like butter and cream. Starchy potatoes are also good for fries as the relatively dry and well separated cells give a ‘fluffy’ internal structure.

So we now know how to get a fluffy interior, use starchy potatoes, but we also need the crunch and colour on the exterior of the fry. The usual way of achieving this is to fry them twice. Once at lower temperature, around 120/250F, and again, after a short rest, at a much higher temperature, around 190C/375F. The first fry is not only to make sure the potato is cooked through, that is all the starch has been gelatinised, but also to get some initial crisping of the chips’s exterior.

The gelatinised starch can leak from intact potato cells, so after the first stage there should be a layer of gelatinised starch on the outside of the fry. The short rest, apart from reducing the chance of overcooking the chip in the second fry, also allows more gelatinised starch to leak out onto the surface of the fry. The second fry at high temperature finishes cooking the gelatinised starch on the outside of the fry for crunch and also provides some Maillard reactions to give the golden colour of a good fry.

Crucial to the development of a good exterior during the second fry is the integrity of the cell walls. The cell walls add some structure to the outside of the fry and if the cell walls have broken down before the starch granules burst then the granules will crumble away without forming the crust. To avoid this potatoes are often blanched prior to frying to reinforce the cell walls. For example, McDonald’s blanch their fries at a temperature between 60C/140F-70C/158F for 15 minutes before drying and frying.

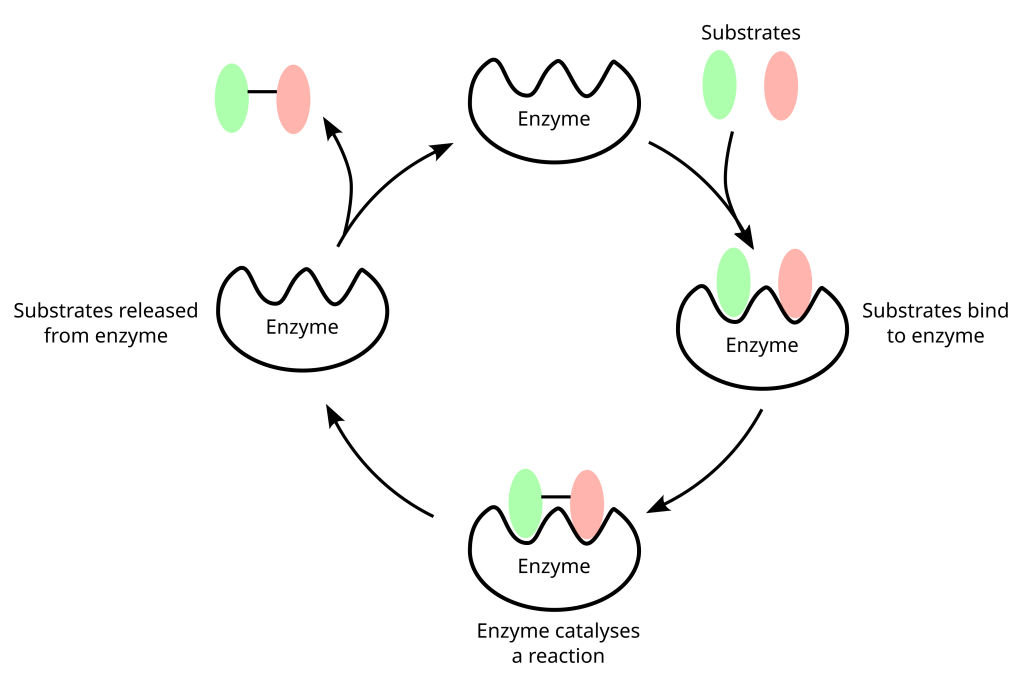

The theory behind blanching is that it gives an enzyme that occurs naturally in potatoes, called pectin methylesterase (PME), a chance to strengthen the pectin molecules that support the cell walls. Enzymes are proteins that catalyse chemical reactions (a fancy way of saying that the enzyme forces a chemical reaction to take place faster than it would naturally). PME joins pectin molecules together creating higher molecular weight pectins with greater heat resistance (see here for some real science on PMEs). Enzymes operate within a specific temperature range and PMEs aren’t active until 60C/140F but stop working after 70C/158F. So blanching at a temperature somewhere in between these temperatures for some period of time gives the enzyme a chance to strengthen the cell walls. Apart from reinforcing pectin, a second benefit to blanching is that it also washes away simple sugars that can burn and give a bitter taste and ugly burnt appearance to the fry.

OK, we now know how to make restaurant quality fries. If you want good fries blanch them at precisely 65C/149F, maybe freeze them for a while to dehydrate them, fry them once at 130C/265F, rest them then cook again at 180C/356F, job done. The problem is that we are home cooks and don’t have things like deep fryers, water bathes (OK, I’m a science nerd so I do have a water bath but I’m too lazy to use it) or the organisational skills to pre-freeze some blanched fries.

Moreover, we are frying in a small amount of oil in some receptacle heated by our hob (or grill, I often deep fry outside). In these conditions we need to batch our fries because if we put too many in the oil it’s temperature will drop way too much to get a good fry. Once we start batching timing becomes an issue, the first batch will be cold long before we’ve got our oil back up to temperature and fried the next batches. It all seems a bit difficult, french fries take too long and need special equipment, so what are we to do? Are there shortcuts we can use to get some decent home made fries? Luckily there are.

The chef Joel Robuchon gets the prize for the producing fries with the lowest amount of effort. Simply put some uncooked fries into cold oil in a pot and put the pot on the burner. After about an hour you have some fries. An hour is still a long time but there is not much effort required and the chips, while not as crunchy as the traditional method are still pretty good fries.

Harold McGee suggests skipping the rest period and just starting the chips in a low temp oil and after ten minutes turning the temperature up. This also works pretty well though you still need to batch your fries or the temperature of the oil will drop precipitately in the low temperature fry. I’m also thinking he has some good equipment as my home hob doesn’t have the grunt to get oil up to different temperatures that quickly.

You could boil your potatoes first then do a high temperature fry, though J. Kenji López-Alt did this and got fries with a crispy layer half as wide as chips cooked using the double fry method. But Lopez-Alt also found a way of strengthening pectin the the cell walls by using acid, which stabilises pectin, blanching his fries in boiling water spiked with vinegar (roughly one tablespoon per litre) before frying twice as per usual.

The method I use, which produces pretty good fries, is an interesting study in ignorance bumbling it’s way to some sort of success. Arising out of a desire to cook fries with a minimum of effort (I didn’t know about the Robuchon method or I would certainly have used that) I basically parboil potatoes, stick them in the fridge and then dump all of them into hot oil when I’m ready to cook them. Now I know some the science I can see why this implausibly worked.

Firstly, when parboiling my potatoes, I start them off in lots of cold water. By starting in cold water I now know that I’m giving PME a chance to do it’s thing. It takes ten minutes or so for the water to start boiling and while it’s getting up to temperature it spends some time in the 60C/140F-70C/158F sweet spot for PME activity. It’s not as effective as blanching at 65C /149F for 15 minutes but it’s something. Once cooked, I give the potatoes a wash and let them cool in the fridge, unwittingly giving the potatoes a chance to dry out and get rid of some of the water that is the enemy of good fries.

I normally cook my fries in a wok on a charcoal grill. So I heat some oil to around 180C/356F and then put all the fries in the hot oil, that is I don’t batch them. Because I’m adding so many fries the temperature of the oil drops precipitately down to around 120C/248F. As the wok is sitting on a blazingly hot charcoal grill the temperature starts climbing again and I let the fries cook till the oil slowly gets back up to 180C and the chips turn golden. By doing this I’m basically following the McGee method of starting with oil at low temperature and turning up the heat, even though I didn’t know that until now.

For me the major advantage of this method is I can cook my potatoes well in advance, keep them in the fridge and start frying them when it is convenient to get everything on the table at the same time. Are they the best fries in the world? Definitely not. Are they good enough that I get the odd ‘nice fries’ compliment? Yes they are. And that’s good enough for me.

In this post I’ve barely scratched the surface of potato cookery and french fries. Others have gone much further down the french fry rabbit hole. For example, the International Culinary Center summarises their method for french fries (part one is here) as follows:

Soak the cut fries for one hour in a room temperature solution of Pectinex SP-L (a pectolytic and hemicellulolytic enzyme mix), blanch in boiling water (don’t overload your blanching container) for 14 minutes 30 seconds (assuming your water takes 1:30 to get back to boil), do not dry before frying.

I enjoy their dedication to solving the mysteries of french fries but there is no way I’m doing this on a Saturday afternoon while trying to entertain friends and family. J. Kenji López-Alt has developed a much more user friendly methodology in detail in his book and his blog (and here as well by Sho Spaeth), and this is well worth reading (and stealing). Harold Mcgee is, as usual, also well worth consulting when developing a method for your own fries. I’m probably going to stick with my method, because I’m lazy and generally have other things I’m trying to cook apart from fries. But I will be adding some vinegar to my water when parboiling my spuds to see what happens. Either way I hope that the science we’ve learned here gives us surer footing when we go down the internet home made fries rabbit hole.

Other stuff

Dont eat green potatoes

From the plants perspective potatoes are not really meant for consumption by other organisms. They are the future of the plant after all. Unlike fruits, which plants want us to eat, plants will often produce chemicals in parts of the plant that they don’t want eaten. Potatoes are an example of this and they contain significant levels of alkaloids that are intended to deter insects and herbivores from eating them. Considering the amount of potatoes that are eaten world wide, the strategy didn’t work too well when it came to humans. But under stressful conditions and high light levels the amount of these chemicals in a potato can triple becoming potentially toxic to humans. As light also induces chlorophyll formation if a potato is green either throw it out or peel all the green bits off. You’ll often see some greenness about your potato if you leave it in the cupboard too long though at a few supermarkets I’ve bought potatoes that had been pre-greened, very disappointing.

Leave a comment