Every home cook has been there. You want to make your own pasta, but how? I know – you think, I have at my disposal the single greatest tool for the dissemination of information in the history of man, the internet. I’ll get on that thing and I’ll be an expert in no time. Several hours later you stumble away from your computer glassy-eyed, dishevelled, confused and a little dumber. You know that there must have been some good information in there, amongst the multitude of websites that had clearly copied from each other in a whirling circle of disinformation, the obviously AI generated content, the barely literate ramblings of content farmers, the endless arguments in Reddit forums and the conflicting opinions of well meaning but woefully ignorant food bloggers who strayed too far into the realms of food science for their own good. How do you make sense of it all?

The problem is that pasta is so ubiquitous, who hasn’t eaten pasta, and is so simple, flour and water for gods sake, that people think it will make easy subject to write about. Well it is not. Because, despite it’s apparent simplicity, pasta relies on some truly deep protein chemistry, so deep that at least two of the worlds great culinary traditions, Chinese and Italian, have spent centuries exploring this chemistry and in the process created rich cuisines based on noodles and dumplings. I’m aware of the irony, I am merely adding to the online pasta cacophony, but I’m actually a scientist, specifically a protein chemist god damn it, surely I can go to the science to understand how to make better pasta? Well lets find out.

It turns out that the science of making a good pasta is all about gluten. In fact at least half of dough making and baking seems to be about gluten. Bakers talk a lot about the ‘development’ of gluten and a lot of baking boils down to controlling this ‘development’ in whatever dough you are making. Gluten is the molecule that provides the strength of a dough, it’s ‘chewiness’, and the more developed your gluten the chewier your final product. For things like cakes and shortbread you want to limit gluten development, no one wants a chewy cake. For breads you want some strength in your dough but not so much that your bread is, well, chewy.

There are a whole bunch of techniques and ingredients that are used to control gluten development in baked goods, but what makes pasta a good place to start learning about gluten is that you want a robust dough using only flour and water (often using eggs as your source of that water). There are no fermenting organisms, oxidisers, shortenings or fancy techniques for controlling gluten development that you find when baking breads or cakes, it is literally just you and the gluten and the experience you gain developing a nice strong gluten network will give you a good feel for gluten if you decide to go deeper into baking.

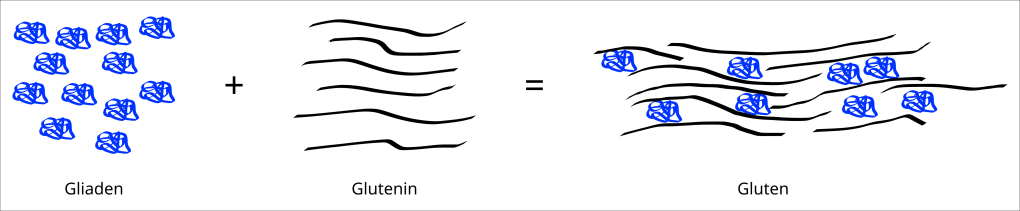

What we call gluten is actually the structure formed by multiple insoluble flour proteins when flour is exposed to water, the two important ones being glutenin and gliadin (if you aren’t sure what proteins are have a look at the protein chemistry quick bite, but for now proteins are very large molecules that are one of the building blocks of life, everything alive, including us, are partially made of proteins). When water is added to flour the glutenin proteins, that are long and ribbon-like, start to interact with each other, kind of like droplets of oil in water. These associations result in long bundles of glutenin that are stabilised by chemical interactions between the individual glutenin molecules.

Gliadin, on the other hand, remains in a more rounded ‘globular’ state but it ends up interspersed through the gluten bundles where, importantly, it interacts only weakly with glutenin and other gliadin proteins. Because the gliadins interact only weakly with other proteins they act as a lubricant allowing the long glutenin chains to slide past one another as the gliadins block the glutenin interactions that would otherwise prevent movement. Without gliadin our dough would just be a stiff unworkable mass of coagulated glutenin.

This unique protein complex is what we refer to as gluten and all the palaver of kneading, resting and rolling during pasta production is aimed at building a network of gluten that is comprised of organised long glutenin chains that are stretched out to an extent that the dough is under some degree of tension and has the tendency to move back towards it’s original form when stretched (i.e. it’s elastic) but not stretched out so far that any attempt to stretch it further will cause it to tear (i.e. it’s plastic).

The process of forming this gluten network is what we call developing gluten, that is forming a dough that is both plastic and elastic, a combination that allow us to roll out robust noodles or shape all the different types of pasta you see in the pasta aisle. Once you understand this it is easy to see what state your dough is in when making pasta. If your gluten network is underdeveloped it will just be a weak blob that cant be formed into anything, if it is overdeveloped then it will just tear when you try to do something with it because the gluten is stretched to its limit. You just need to hit that sweet spot in the middle.

The first step in making pasta is to mix the flour with some type of moisture (usually eggs or water), form a bit of a rough dough and knead for a while until the dough is reasonably stiff. We now know enough to see whats going on here, we’re hydrating the dough, none of the gluten magic happens without water, and we’re starting to get the gluten network developed.

The next step is leaving the dough alone for a while, what professionals call letting the dough rest or relax. ‘Relax’ turns out to be a pretty good description of what is going on here. The gluten has kinks and coils which are stretched out as you first knead the dough, much like stretching out a spring. The new ‘stretched’ out state of the dough is stabilised by new protein interactions. When you let the dough rest, these coils and kinks slowly ‘relax’ back toward their native conformation and the dough becomes easier to work with as the tension in the dough partially dissipates. In other words, as the gluten network is stretched you are breaking protein interactions and forming new ones that stabilise it’s new stretched out state, leaving the dough to rest is giving it time to reach some equilibrium between the tension created by the stretching and the strength of the new protein interactions that are stabilising it, some of them break some of them don’t.

After the rest you start ‘rolling’ out your dough. If you are a Nonna you just use a long skinny stick but for the rest of us it is easier to use a pasta machine to roll the pasta out into sheets, laminating as you go. Once again this is aimed at getting your gluten molecules organised but it also forces out air bubbles that can prevent the gluten molecules from forming their chemical bonds thus weakening your dough and it also starts reducing the elasticity of the dough so it can be more easily shaped.

Aesthetically you also want a nice thin noodle or dumpling, no one wants to eat a thick wad of pasta and a nice delicate pasta is considered more appealing. You will also run into problems cooking your pasta if it is too thick. The outside will be overcooked and the inside will be raw, so thin is better for a number of reasons. After a bit of time rolling out your dough, eventually you’ll have a nice smooth sheet of strong dough that you can slice, dice or shape into whatever pasta shape you require.

Now that we have a handle on whats going on when you make pasta lets have a look at what this science means for your pasta. First up choice of flour. We want a strong dough so it makes sense that the more protein in your flour the stronger the dough will be. Durum wheat, or semolina, is the strongest flour, it has the highest protein content, it’s also already yellow so you can just use water as your moisture and have a great pasta. You could also just buy some equally good dried pasta for a few cents but it could be a good choice to make at home if you are making a stuffed pasta (ravioli or tortellini for example) and you’re worried about the strength of your pasta. If you also want some of the silkiness of egg made pasta, use eggs instead of water with semolina.

If you are like me you may not be organised enough to always have some semolina around the house, so use common flour. High protein common flours like ’00’ have plenty of protein but this is where you starting adding eggs instead of water, mainly for colour but also for some extra protein, for some chemistry involving starch (which I have totally ignored) but also for the silky egg-pasta feel that you don’t get with dried pasta. You can make perfectly good pasta with all purpose flour but when you get to flours with a lower protein concentration, say for cake making, you might start struggling to get a lot of strength into your dough and end up with very fragile pasta.

What about fats and oils in your pasta dough? You may have heard of ‘shortening’ a dough. When you shorten a dough you add some kind of fat or oil to the dough which makes the dough weaker as fats and oils prevent the glutenin interactions that we rely on to form the gluten complex, think about all the fats that get added to a cake where you don’t want any gluten development. The reason that this works is that the interactions formed between glutenin proteins are what are called hydrophobic interactions. Hydrophobic literally means ‘scared of water’ and the way hydrophobic molecules and hydrophobic parts of proteins interact is one of the most important concepts in biochemistry.

Proteins have what is called a surface ‘electrostatic potential’, parts of the protein surface have a small negative or positive charge and other parts have no charge at all, they’re neutral (see the protein quick bite for more on this). Hydrophobic interactions occur when neutral regions of a protein, or other molecules such as oils or fats, prefer to interact with other neutral molecules rather than water. Once again think about drops of oil in water. Oil really doesn’t like water so it will form little globules in the water and if two of these globules run into each other they will immediately form one larger globule. Oil in water will always end up arranging itself in a way that minimises the surface area exposed to the water. Proteins do the same thing, when water is added to flour the glutenin molecules arrange themselves so that their hydrophobic parts are interacting with the hydrophobic parts of the other glutenin proteins and not water, that is how gluten forms and how it sticks together.

Of course molecules don’t ‘prefer’ to do anything these interactions are driven by the laws of physics and concepts like free energy, but for our purposes a bit of anthropomorphism is OK. What we need to understand is that the gluten interactions are hydrophobic, so if you add an oil or fat, both of which are hydrophobic, they will also want to interact with the hydrophobic parts of the glutenin and not the water. When they do this they will prevent the glutenin proteins from interacting with each other and so weaken your gluten network.

When we make pasta we are trying to make a strong dough so any oil or fat is going to weaken the dough to some extent. So olive oil, a common addition to pasta dough, might be good for flavour but you are shortening your dough and making it weaker. If you like olive oil go for it but be aware that the trade-off is a slighter weaker dough so if you want a strong dough for something like ravioli leaving out the olive oil might make your life easier, if making fettuccine the slight reduction in strength probably wont matter at all. This is also the reason that egg pasta is ‘silkier’ than dried pasta, made from durum wheat and water, the fats in the egg yolks are shortening your dough.

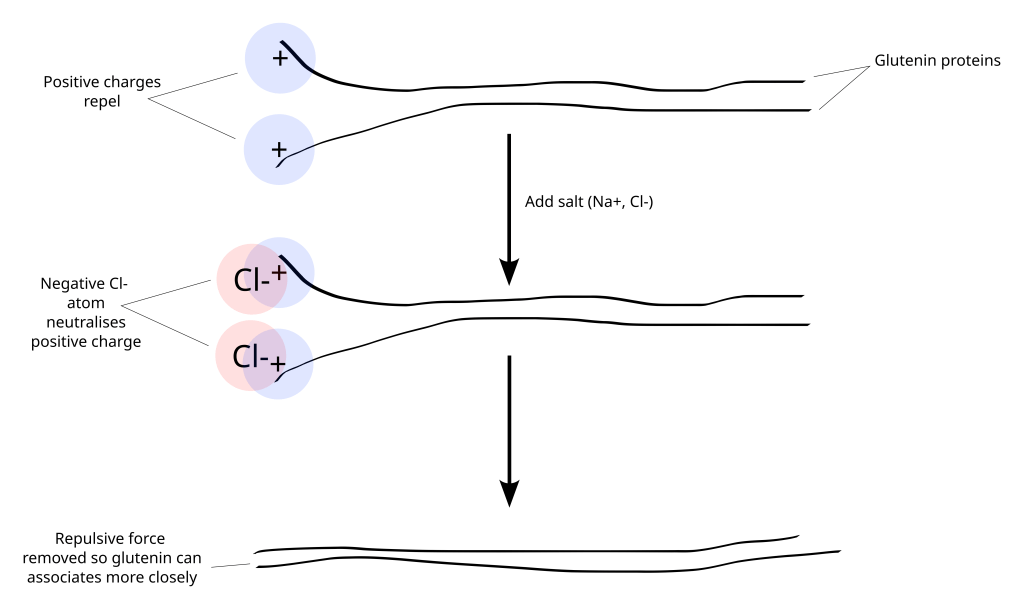

Salt also affects the interactions between glutenin proteins but, unlike oils and fats, salt will strengthen your dough. Salt is an ionic compound which means it is composed of charged atoms that neutralise each other. Salt is made up of negative sodium atoms (Na-) and positive chlorine atoms (Cl+), and when you add salt to your dough the ions will dissociate in water and start interacting with the charged parts on the glutenin molecules. As negative charges will associate with positive charges, and vice versa, the net effect will be that any charge on the glutenin will be neutralised. Glutenin does have some positive charges, so adding salt will neutralise these charged parts of glutenin reducing the repulsive force between individual glutenin proteins caused by the proximity of similar charges. The removal of this repulsive force allows glutenin proteins to associate more closely and form more interactions which means your dough will be strengthened.

Acid has the opposite effect, the effect of acid on proteins is a complex and important process (that will be covered in later posts) but for our purposes here acid in dough will promote the formation of positive charges on the glutenin proteins (in technical terms most free amines will accept hydrogen atoms and become positive while most acidic groups will not be ionised meaning an overall positive charge for the protein). These positive charges will repel each other weakening the association of the glutenin proteins with each other and weakening your dough. This isn’t really a consideration for pasta dough, I haven’t seen a single recipe suggesting the addition of an acid, but it does become a consideration when baking, for example, sourdough where the sourdough starter is acidic and can weaken the gluten network.

The hydration, a fancy word for how much water you’ve added, of your dough has a big effect on your pasta. If you don’t have enough moisture then a lot of the gluten in your dough wont be properly interacting with the other glutenin molecules and your dough will be crumbly and weaker than it should be. Too much moisture and your dough will be too hard to work with and the gluten proteins will be too dilute to interact properly. This can be a bit of a problem when making egg pasta, recipes call for a certain amount of flour and, say, two eggs. You can weigh the flour but eggs come in big array of sizes if you blindly follow the recipe you might run into troubles based the size of your eggs. Likewise, different flours can ‘handle’ different amounts of moisture, so a certain amount of moisture will be perfect for one flour but no good for another. Unfortunately, a recipe can’t account for all this variation so you just have adjust the amount of flour and moisture in each batch of dough. Remember the dough should be plastic and elastic and eventually, actually quite quickly, you’ll get a feel for how you want your dough to feel.

For something that involves mixing two ingredients, flour and water, there is a lot to going on in pasta. This is a long post and there is a lot of chemistry (I’ve also exclusively concentrated on gluten development in this essay, ignoring starch and it’s chemistry and science) but hit me up on Bluesky if you have questions. But also take heart that the science we’ve picked up learning how to make pasta is applicable all over the place when it comes to cooking, baking is just one area this chemistry will help you. You’ll find a lot of stuff on the internet about pasta, some of it is great but a lot of it is correct for the wrong reasons or wrong for the right reason or just plain wrong. So hopefully having a basic understanding of the science behind gluten will give you an advantage when wading through the verbiage. The important thing is knowing enough to have the confidence to make the pasta that is perfect for you.

Extra stuff

Safety considerations when making fresh pasta

It is important to realise that almost all dried pasta you buy in the store is made from Durum wheat and water, no eggs. Fresh pasta, what you typically make at home, is normally made with eggs. That’s the whole point of making fresh pasta, you want the silkiness that the eggs bring to the pasta. But, if you are adding eggs you do need to realise that it makes the pasta perishable and it should be cooked or refrigerated pretty quickly after being made. Anytime you a dealing with uncooked eggs there is a small risk of salmonella contamination. If you leave your fresh pasta lying around at room temperature to dry, those horny bacteria can reproduce really quickly to sickness inducing levels. You can certainly make dried semolina pasta with water at home but really is it worth the effort when you can get something equally as good for a few cents at the store? You put in the effort to make pasta at home to get the silkier pasta that comes from being made with eggs.

Overworking your dough

One of the things that makes pasta easier than other forms of baking is that though it is theoretically possible to overwork pasta dough I think the far greater risk is under-working the dough. When kneading by hand it’s generally recommended that you work on it for approximately 10 minutes. I don’t know about you but by the end of ten minutes I am well and truly ready to stop, so over kneading has never been my issue. It’s really an issue when using a food processor or mixing stand. But if you have a feel for the dough you should have no problem stopping the kneading at the appropriate time no matter what method you are using. So either experiment with your tech or do it by hand a few times first so you know what the dough should feel like then use the tech.

Italian and Chinese traditions

The differences between the Italian and Chinese noodle and dumpling traditions sometimes comes down to the types of flour available to the cooks in these areas. In Italy access to strong semolina enabled the development of dried pasta and the creation of a wide variety of shaped pasta, although softer fresh pastas where also developed using bread flour. In China noodles and dumplings were made from flours with much lower protein content leading to a rich fresh noodle and dumpling tradition, also with a much higher salt content which, as we have seen, stabilises the weaker gluten network.

Also Marco Polo definitely did not bring pasta to Italy, there was pasta in Italy centuries before then, but the Chinese were definitely many centuries ahead of the rest of the world when it came to making noodles and dumplings from wheat flour.

Leave a comment