I’m a chemist and an enthusiastic amateur home cook. You tend to find a lot of us, scientists who enjoy cooking, and for me, and I suspect other scientists, this is because cooking uses the same skills I learned working in the laboratory. In both cooking and chemistry the careful application of heat and time to matter results in a “thing” that we desire: a particular chemical, a new drug, a perfectly seared medium rare steak or a thick emulsification of oil and egg for slathering over a hamburger bun. The cook and the scientist are both using the laws of nature to change the molecular structure of matter to produce something of greater value and, I’ve got to say, this makes you feel pretty damn good, you know, the mad scientist, dominion over nature and all that.

I know a lot about chemistry and a little about cooking. Is that enough to presume to write a cooking blog? What can I contribute, a decidedly amateur chef, to the culinary world? First answer would be let’s find out, but the second is the subject of this, my first post. What can science do for you in the kitchen? I’m going to try and persuade you that learning the proper techniques of cooking and, this is important, their underlying scientific principles, will do a lot more for you than blindly following recipes. Anyone can follow a recipe but, despite the three thousand word long recipes you come across online these days, no recipe can tell you everything about how to cook a dish with the specific ingredients and equipment you have on a particular day. Likewise it’s pretty useless learning a cooking technique without knowing why this technique works. If you know why it works you are confident to apply it when necessary and also, perhaps, use it in a way no one else has used it before.

Apart from porn, no subject has as much online activity around it as food and cooking. There is an enormous amount of cooking verbiage out there on the web, some of it good, some of it well-intentioned, some of it just plain wrong. Adding to the problem is the sheer amount of words that are generated on cooking blogs and vlogs. In food blogging, search engine optimisation rewards longer posts so we now have 3,000 word expositions on boiling water. There is no place online for the laconic.

People did build brands around food way before the internet but there was often some type of editing and publishing process. The internet removed the editors and the result is 100,000 unedited, unverified and unchecked pages on how to make pasta. On the internet you now need to have a certain level of cooking expertise so you can make sense of the cacophony of contradictory opinions. Onions are a good example of this. The internet is full of people caramelising their onions in five minutes. It takes 45 minutes to an hour to properly caramelise onions. Most of the time, I think, they really mean brown the onions but you have to admire the ambition, what a wonderful world it would be if we could whip up some French onion soup in just five minutes.

But, even if the internet contained only fully curated, proofread and verified recipes you would still have a lot of recipes for the same dish. This is because cooking success, if you haven’t burnt the rice or served raw chicken, comes down to opinion. This is one of the ways that cooking differs from science. A scientist, after conducting an experiment, doesn’t invite her friends over to sample her new chemical over a few glasses of wine. No, the scientist runs some tests and success or failure is judged according to a set of rigidly defined parameters. Cooking is not judged like this, instead we have the vagaries of human opinion. One persons perfect is another’s bored shrug.

A lot of these opinions are formed in our youth, we have our favourite foods, normally prepared by a mother or grandmother, and a preference for the way grandma cooked things with us for a long time. These preferences also end up on recipe websites as the one true way to make the dish. Consider pasta, some people like chewy pasta and some like smooth pasta. Either is good and either will please some of the people some of the time. But, if you know that the ‘chewiness’ of pasta is a consequence of gluten development then you know that a recipe that calls for durum flour and a good thirty minutes of kneading is going to produce some pretty chewy pasta. If a recipe calls for olive oil, chances are it’s going to be a bit smoother. Point is you know, kind of, whats going on and have the confidence to alter the recipe to you or yours preferences. Once you understand the science behind the recipes you can go out on your own, do some experimentation, make a pasta that is perfect for you.

When it comes down to it once you have learned a little about the science underpinning cooking you don’t actually need recipes at all. You don’t need to read the 1500 words of text accompanying a simple pasta dish. Often all you need is the title of a recipe, because recipes should be inspirational not instructional. Once you understand how to make pasta you don’t need to read about it in every single pasta recipe. What you are interested in is a novel combination of flavours or an ingredient treated in an unusual way (so you can steal it). I’m not naive, of course all this ostentation in food writing is there to make money. But if you are serious about becoming a better cook you are better off ditching the food porn and learning some of the basic science of food preparation. There’s plenty of time for browsing food porn after you’ve made dinner.

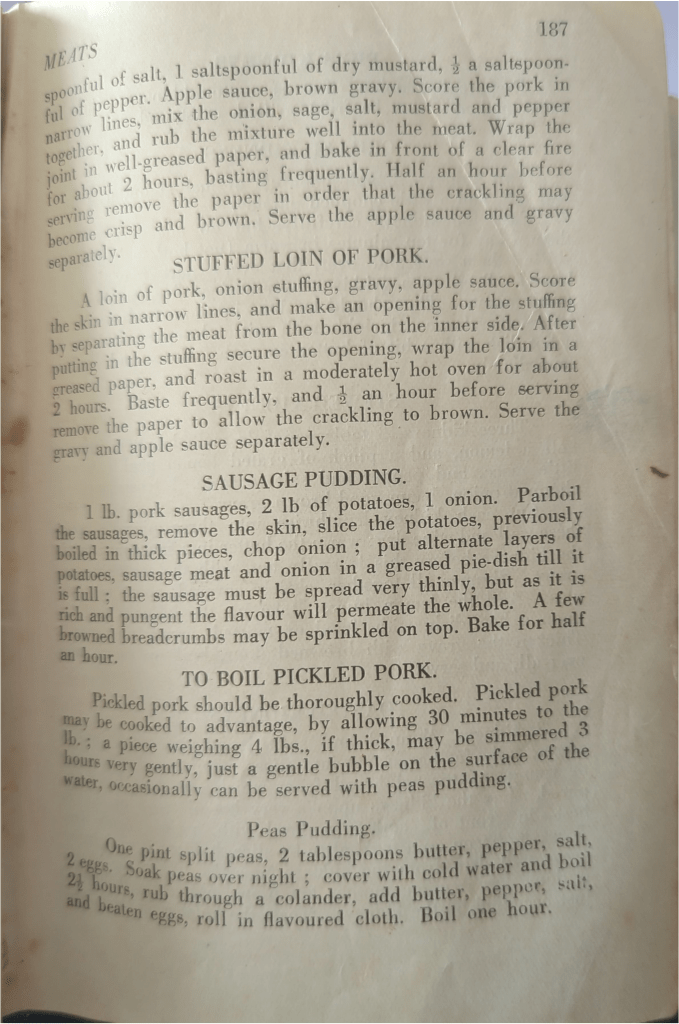

I don’t think it was always like this. I have a cookbook that belonged to my grandmother, published in 1928. It is the size of a small hardcover novel and contains 2,200 recipes in 607 pages. Let me say that again 2,200 recipes in 607 pages – that’s 3.6 recipes per page. This is not food porn, this is more akin to a hammer or a power tool for a home cook. No guide rails just concise instructions addressed to someone assumed to have a certain level of expertise. If you lose an arm, well that’s your problem buddy. Here is a recipe for Sausage Pudding (if you are Australian it’s interesting that there are no pasta recipes in the 2,200 recipes, clearly Australia had no use for that fancy Italian food in the 1930s):

A mere eight lines of text and the book is crammed with recipes of about this length. It’s like food blogging was banned and all online recipes had to be published using Twitter. Recipes like this demand a certain level of skill in the reader and back in the day a certain part of the population was trained in cooking. Obviously these people were woman and of course this reflected the institutionalised sexism of the time. Women then were expected to be trained in cookery either informally in the home or formally in home economics classes1. But, old injustices aside, the point is when you have a certain amount of expertise recipes become a lot more concise and the focus is on the idea behind the dish. Once you learned a few basics you don’t have to read the 1300 words or watch the 45 minute video. These people are drip feeding a few tiny nuggets of knowledge and the price is your precious time and your participation in their brand building exercise. I like food porn as much as the next person but, like the other type of porn, you shouldn’t learn everything you know about cooking from it.

So, sounds easy learn some science, but, I hear some of you say, I’m not a scientist, I failed science at school because it is so boring. Atoms and molecules, covalent bonds, pH levels – come on this is more boring than church. But, my answer would be, you don’t need to get a PhD to become a better cook. You don’t need to understand chemistry like say a medicinal chemist does. What you need is a model in your mind that is adequate for what you want to do. If you are making bread or a cake you need to know about the proteins found in flour and gluten development and the effect of fats and oils on that process. You need to know what’s happening when you apply heat to matter. What types of foods need slow cooking and which can be quickly cooked over high heat and how that is related to the chemical structure of those foods. What does acid do to food and what is an acid for that matter? A bit of knowledge on the molecular basis of taste is probably a good idea and a bit of microbiology is a must so you don’t kill the people you are feeding. It is not that much really and anyway I’m writing a blog on it so you can learn all about these things here.

As I said I’m a scientist and biochemist and I’m not interested in brand building. What I am interested in is seeing how far I can get with building a body of scientific knowledge that is accessible and useful for the home cook. I am not going to go full nerd, the home cook doesn’t need that level of knowledge so it will be consistently aimed at building an easy to understand model of cooking based on science. If you are really interested this should give you a good starting point for further investigation, but if you are happy with that level of understanding it will hopefully be good enough to have a direct impact on how you cook and interact with food. The payoff for this little bit of learning: a much enhanced ability to detect bullshit in online food writing, freedom from the tyranny of recipes, much greater ability to improvise in the kitchen and the warm inner glow you get from the effusive praise of friends and family for feeding them well and not killing them in the process.

Footnotes

- I am in the Anthony Bourdain camp when he suggested that they missed a trick abolishing home economics for women when they should have made it compulsory for both men and women. ↩︎

Leave a comment