In the first post of this microbiome series I covered the beginnings of microbiology. The realisation that we were surrounded by microorganisms, the development of germ theory and the first stirrings of the idea that microbes, apart from destroying our health, could also be contributing to our well-being. We left the story in the early 20th century, an exciting time that saw, at last, the discovery of Mendel’s work, the beginnings of genetics and advances in other fields that laid the basis for an astounding series of breakthroughs in our knowledge of the gut microbiota that continues to this day.

I am, however, going to skip over all this important work done by many dedicated scientists, including in a very small way myself, and try to give a high level view of the way that we interact with our gut microbiota and, how it interacts with us. Although the words “microbiome” and “microbiota” are often used interchangeably, there is subtle difference in their meaning that reflects they way we are now coming to see the microbial community that we all carry around in our gut. In technical terms, the word “microbiota” just refers to the actual microbes that live in a specific environment whereas “microbiome” refers to a microbiota, their collective genetic potential, their metabolites and the environment they inhabit, in other words a micro-ecosystem.

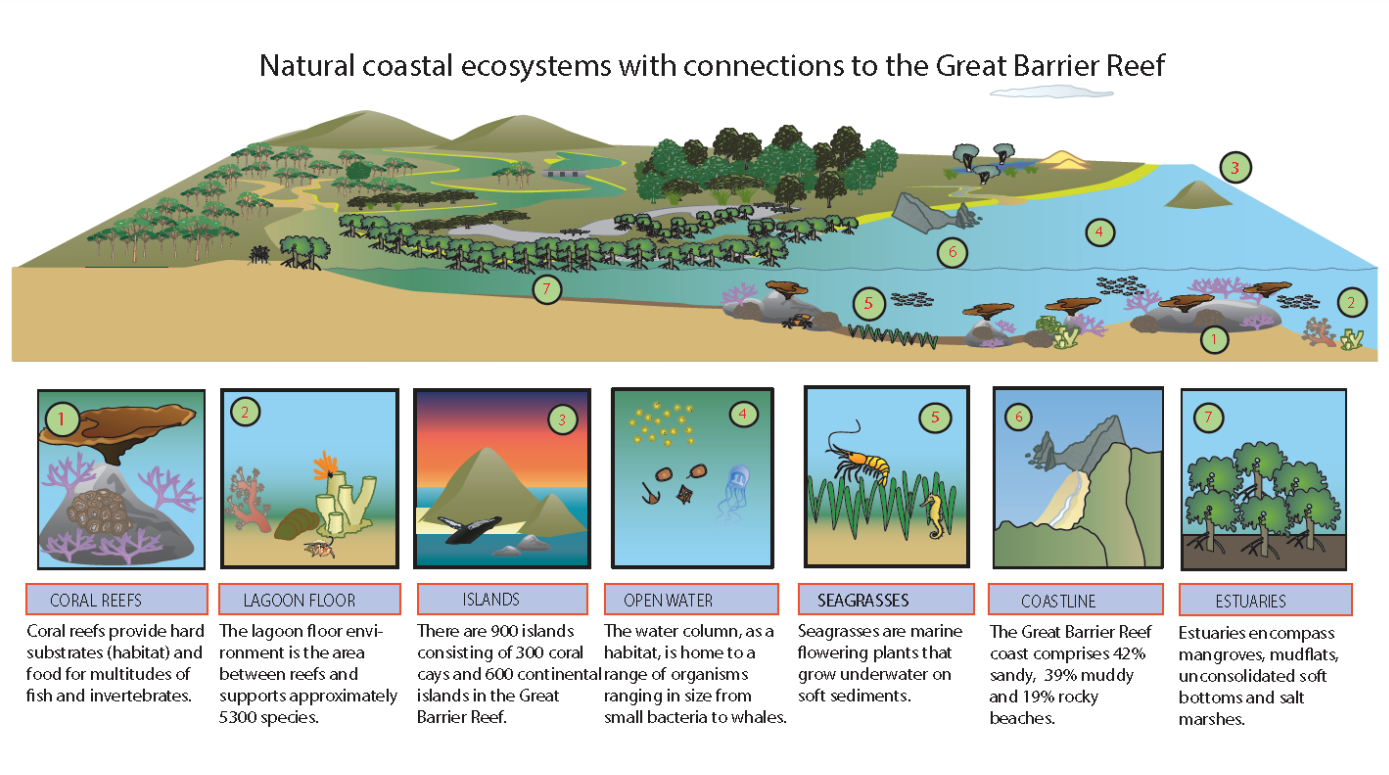

As a species living on Earth we’ve realised, hopefully, that we can’t just go around destroying every other organism we come across. We know that we depend on other organisms and that things like clean water, breathable air, sustainable food, a comfortable climate and even things like flood control depend on us maintaining a healthy and diverse ecosystem. The intersection of our microbiota and our health is the same story writ small. It’s becoming accepted that increasing allergies, autoimmune disease and obesity may be the same story of imbalance that we often encounter when considering environmental problems. In this case though it is an imbalance in the unique ecosystem of microbes that make their home in our gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Lets start at the beginning; how we get our microbiota in the first place. Current thinking is that our gut microbiome begins to develop during and shortly after birth1. The vagina has its own microbiota and these microbes seem to be early colonisers of a newborn’s gut2. Babies pick up these microbes as they pass through the birth canal. Vaginal birth seems to be best for our microbiome. There is some evidence that cesarean section babies could have a greater risk of developing allergies, obesity and autoimmune conditions as a result of the differences in their microbiome. Though, some experiments suggest, that C-section babies could obtain a healthier microbiome via the simple mechanism of exposing them to vaginal fluids during birth.

Breast feeding also provides another early exposure to colonising microbes. Bacteria from the mother’s skin and the breast milk itself contribute to the establishment of a healthy microbiome. Breast milk is also an important source of oligosaccharides that act as probiotics, favouring the growth of specific classes of bacteria beneficial to the human gut. Microbes in the childs environment are also important. Babies will develop a microbiota similar to their parents, even if they are not genetically related3, and there is evidence that even pets can influence an infants microbiota4.

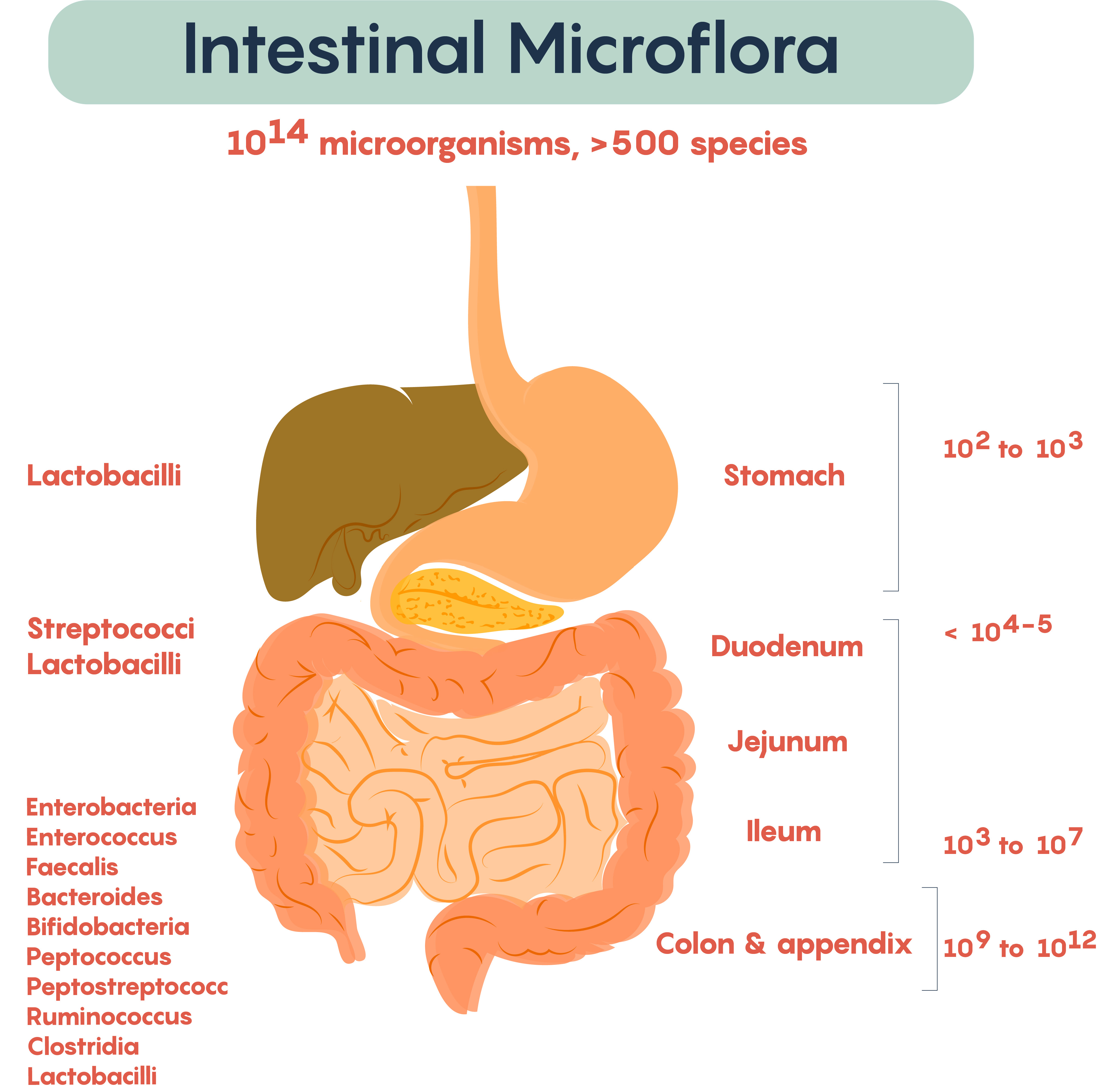

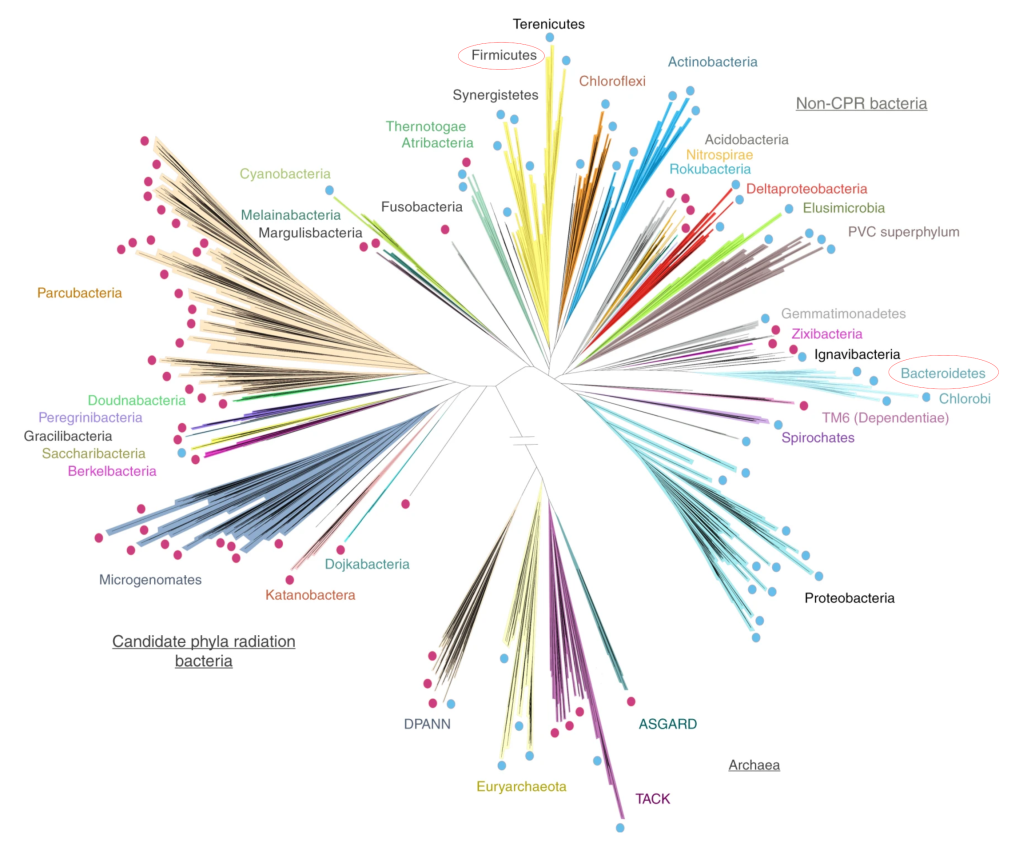

By about 2 to 3 years of age a baby has something that should resemble a healthy adult microbiome. Though what exactly what makes a healthy microbiota is something that is a little hard to pin down. What we can say is that healthy microbiomes are generally made up of bacteria from the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes5, with Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria contributing a small number of species. Together these phyla represent an enormous amount of bacterial species (almost 8,000 species for Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes alone) and this is reflected in the enormous diversity that is found in healthy adult microbiotas. A healthy gut microbiome has a lot of different bacteria6. This diversity means that everyone’s microbiota is different; even identical twins have different gut microbiotas.

Interestingly, studies looking at diversity in the gut microbiota have shown that although the species of bacteria may vary from individual to individual, the bacterial gene expression is very similar7. What this means is that healthy microbiotas have microbes that do the same thing at a metabolic level even though the specific species can be different. Getting back to our idea of the gut microbiome as an ecosystem, we could say that different microbial species can fill the same niche in different healthy microbiomes just like different animals fill the same ecological niches in different geographical locations in the macro world.

All the evidence suggests that a healthy microbiome will stay pretty stable over a reasonable amount of time, for months or even years. But problems can arise when things get out of balance, what is called dysbiosis in microbiome research. In dysbiosis you find less microbial diversity, that is there are less species of microbe present and, potentially, one or two species dominate the population. Just like in an Australian drought, where plagues of mice can occur, when the microbiome is disrupted a small number of microbes can come to dominate the system with some bad consequences for our health.

An obvious way things can get out of balance is when we take antibiotics. Studies have shown that up to a third of the species in your microbiome can have their abundance modified by a course of antibiotics, potentially leading to dysbiosis. For this reason we need to be a bit more wary of antibiotics and we really need to be aware of the damage they can do to our microbiota, especially in children. Not that we should stop using antibiotics, they are a very important weapon in our microbial arsenal. But we need to think about antibiotics as more like a chemotherapy that can have side effects for our microbiota8. Not as a default prescription whenever we are feeling a bit ill. I certainly remember as a child rarely leaving the doctors without a prescription for antibiotics when I had a cold, a practice that, hopefully, has declined as we learn more about our microbiome.

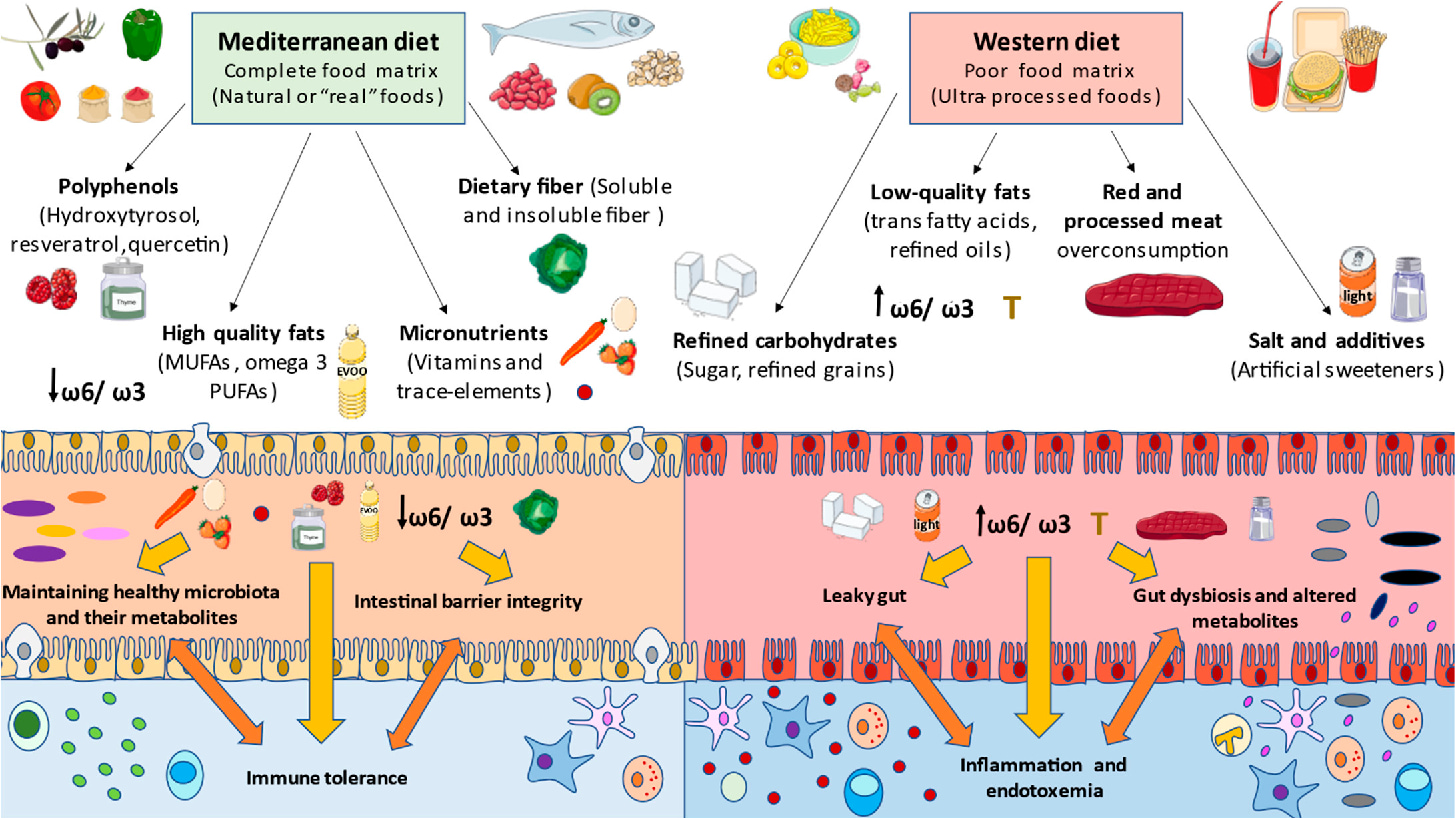

So, what are the consequences of dysbiosis? Well, lots of stuff, far more than I could possibly cover in one post. So, what I will do is take one example of how our bodies and our microbiome strike a delicate balance that is essential for our well-being: the microbiotas role in maintaining the integrity of the tissue that lines out GI tract. This process, also involving what is called mucosal immunity, is a major part of the way that we interact with our microbiota and when things go wrong it can lead to food allergies, autoimmune disease and things like irritable bowel syndrome (IBD).

Our gut is lined by a variety of different cells, one type of which, the Goblet cell, secrete a mucus made up of water and large glycoproteins called mucins. This mucus lubricates the GI tract, provides a physical barrier protecting the gut lining and has some immune functions. Ideally, we want to maintain a certain level of mucus and to do this we need to not only produce it but also break it down, preventing it from building up too much. We achieve this by harbouring mucin-digesting microbes in our microbiota. These beneficial microbes in our gut strike a balance between consuming oligosaccharides, the fibre in our diet, and mucins, such that an appropriate level and consistency of mucus is maintained.

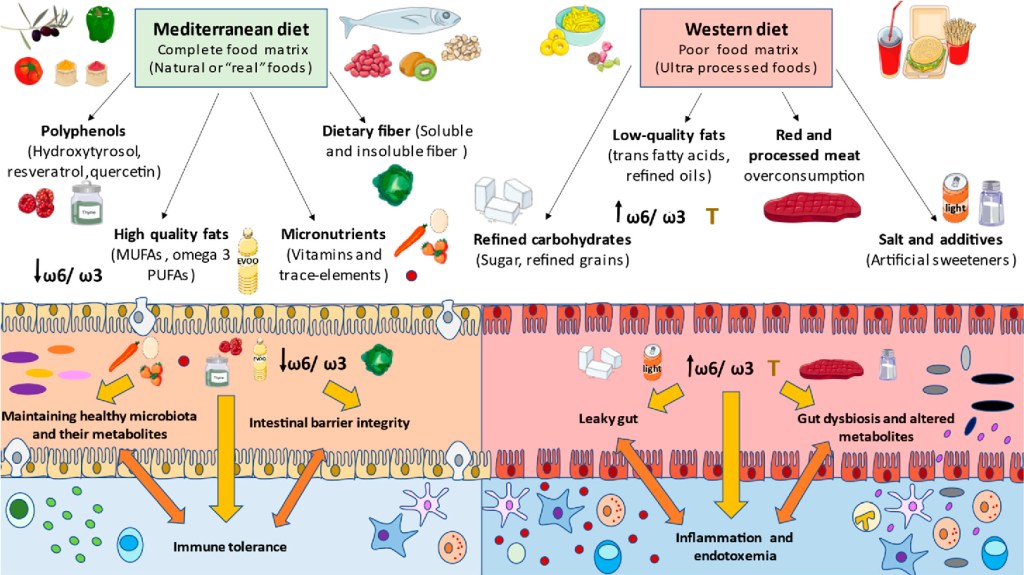

Anything that disrupts the balance of our microbiome is likely to affect this delicate balancing act. As I’ve discussed, antibiotics can be a cause of disruption, but another important factor in maintaining this balance is diet. The Western diet is often, deservedly, held up as the worst possible diet for our microbiota, rich in processed foods, high in sugar and, importantly, low in fibre. When we don’t feed our microbiota enough dietary fibre, our microbes will start looking for other food stuffs and what they find are mucins. So, a diet low in fibre causes the amount of mucin being eaten by our microbes to increase. When this occurs the total amount of mucus may decrease or it’s consistency can become more watery9, either way it loses its effectiveness, exposing our intestinal lining to attack by less friendly microbes10.

Apart from forcing our microbes to eat mucins, a diet low in fibre can actually shift the type of bacteria in our microbiota from beneficial microbes (commonly called commensals) to less beneficial bacteria whose preferred diet is mucins. This is not only bad news for our mucus but it is also important because the commensals interact with our GI tract and immune system in a number of other ways. Firstly, commensals stimulate the secretion of what are called tight junction proteins by the cells of the gut epithelium. These proteins help the epithelial cells form a tight seal between themselves and adjacent cells. Without the commensals our gut epithelial cells may not be as efficient in preventing the passage of microbes and foreign molecules into our tissue where they can cause inflammation; something you might have heard of as leaky gut.

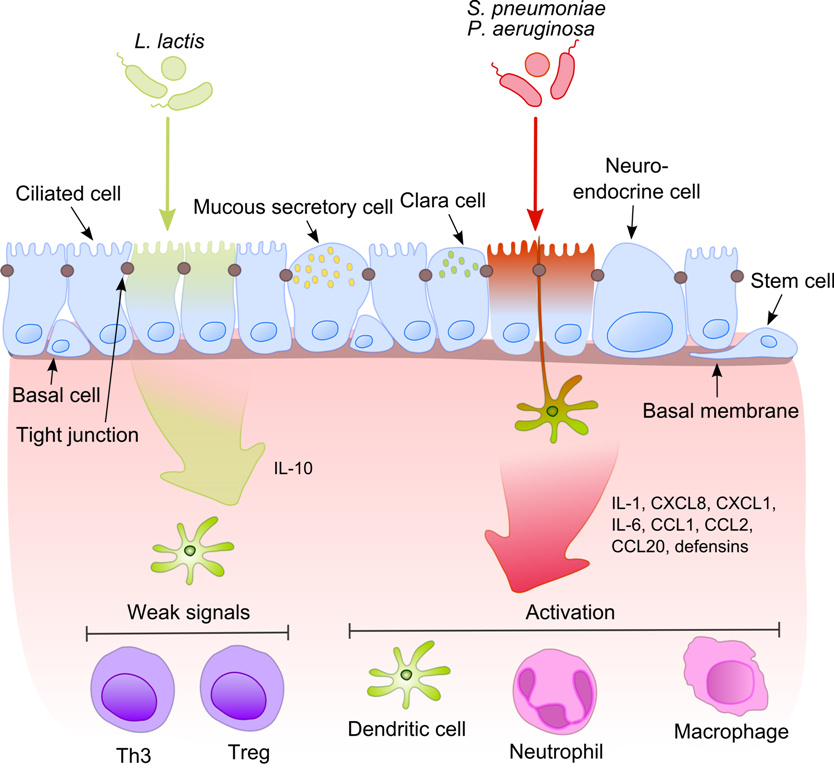

If this isn’t enough, commensals also stimulate the release of antibacterial molecules, called defensins, by some epithelial cells (specifically cells called Paneth cells). Defensins regulate the composition of the microbiome, killing many types of harmful bacteria and fungi, protect us from some microbial toxins and keep microbes in the lumen of the GI tract, away from our gut tissue.

All these things our commensals do for us means that if our diet, or a course of antibiotics, changes the balance of our microbiome away from commensals to less beneficial bacteria there will be consequences. Our mucus lining diminishes, regulation of the microbial composition starts to fail and our gut can start losing integrity. These are all things that we see in the various manifestations of IBD.

Once we start going down this path we can also get into a nasty feedback loop. Because commensals also have a role in tissue repair, if we start losing them our ability to repair our gut tissue can be impaired. Current thinking is that commensals can be recognised by our cells via pattern recognition receptors. In a gut with a healthy microbiome, when the gut lining is damaged the immune system recognises the presence of commensals, moderates it’s response and promotes tissue repair. If commensals are not present and “bad” microbes are, instead of stimulating tissue repair, the immune system mounts an immune response and we get chronic inflammation. This is often also encountered in IBD and it leads to some of the debilitating injuries to the gut lining seen in these diseases11.

If all this hasn’t convinced you to look after your commensals, mounting evidence suggests that they also play an important role in training our immune systems. The immune system is itself engaged in a delicate balancing act, it needs to balance it’s responsiveness so as to produce an immune response against appropriate things, like pathogens, without being so sensitive that it will mount an immune response against inappropriate things, like our own cells or our food. If commensals are not present the immune system never learns how to perform this balancing act and we start seeing things like food allergies, autoimmune problems and allergies. All indications of an overly sensitive immune system that can also be combined with an inability to properly respond to actual pathogens.

I could go on and on, but I wont. There is an enormous amount of research coming out about the human gut microbiome and a lot if it can be quite complicated, involving complex interactions with our immune system, metabolism and blood sugar levels. I haven’t mentioned the gut-brain axis, which is the potential interaction of the gut microbiome with the brain that influences how hungry we are. Some evidence also suggests that this interaction can influence our moods and mental well-being. I haven’t covered how dysbiosis has been implicated in diseases as varied as obesity, diabetes and dementia. I’ve ignored how our microbiome can change as we age and I’ve mostly talked about the gut microbiome, but other microbiomes exist on out skin, genitals, mouth and lungs, among other places, and all of these have more or less important roles to play in out health. Plenty of topics for future posts, I guess.

Whether all this research stands the test of time, who knows? But it is clear that we should all be looking after our gut microbiota and guess what? It is super easy, eat real food, lots of fibre, be careful with antibiotics and have some yoghurt or other probiotic every now and then and a million years of co-evolution will do the rest. If this doesn’t work, visit your doctor, they are the experts. They can also fill you in on the slightly off-putting idea of faecal transplants.

Footnotes

- The currently accepted wisdom is that the womb is a sterile environment and that a prenatal microbiome does not exist, though there is some argument over this. ↩︎

- A well known example are Lactobacillus species. ↩︎

- Part of what makes biology so hard is that there is also evidence that genetics does matter, so, as is so often the case, it’s nature and nurture. ↩︎

- This later source seeming to influence the infant’s immunological development, early exposure to pets has been associated with reduced levels of atopy, another word for allergies, and asthma. ↩︎

- Lactobacillus, for example, is a genus found in Firmicutes (also known as Bacillota). ↩︎

- If I sometimes say “bacteria” you’ll have to forgive me because the microbiota contains fungi, protists and viruses and they can all be part of a healthy microbiota. But the majority of the research has dealt with our gut bacteria so that is what we know the most about and what we normally think of as making up our microbiota. ↩︎

- In one study of twins and their mothers almost 93% of enzyme-level functional groups were shared by all the participants despite minimal similarity at a species level. ↩︎

- Another potential concern is the amount of antibiotics in the environment and in our food due to their overuse in agriculture but consensus hasn’t been reached yet about potential harm given the much smaller levels of exposure. ↩︎

- I’m simplifying a bit here as some forms of dysbiosis can lead to more mucus or a mucus that is way too thick. There are many complications when it comes to our microbiome. ↩︎

- This shift has a knock-on effect of reducing the amount of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that are produced by our microbiota. These molecules are the side product of microbial digestion of complex oligosaccharides and have a role in regulating blood sugar, reducing inflammation, influencing metabolism by promoting fat oxidation and can also act as hunger suppressors via hormonal interactions with the brain. ↩︎

- If my grammar seems weird here it’s because IBD is not a single disease but a suite of diseases including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. ↩︎

Leave a comment