Scientific discovery is very much a story of anomalies. An observation that just doesn’t fit the theory or some small detail that needs an explanation the resolution of which unravels into a scientific discovery. A good scientist values anomalies, they are a sign that there is an opportunity, a guide to something just sitting there waiting to be discovered. Just a glance at the history of science provides ample evidence of this; penicillin, radioactivity, X-rays, viagra and the Big Bang theory are just some examples of scientific advancement arising from an anomaly or serendipitous observation that needed an explanation. In many ways anomalies are the raw materials of scientific advancement.

Some interesting recent research is not only yet another example of anomaly driven discovery but also a potential big step forward in our handling of food allergies. The anomaly in this case is something that has long puzzled researchers: some people exhibit a food allergy when their blood is tested but are are nonetheless able to eat the food with no adverse reactions. Where one person with, say, a peanut allergy will experience a possible fatal anaphylactic shock if they eat peanuts another with ostensibly the same allergy can eat peanuts with no problems.

In this study the researchers noticed that certain strains of laboratory mice exhibited the same kind of behaviour as humans. Some mice were allergic but resistant while others were allergic and susceptible to orally consumed food allergens. In these mice the researchers discovered that the answer to this puzzle could be found in one of the ways that the gut interacts with our immune system. In particular, the way food allergens are presented to immunoglobulin E (IgE) bearing mast cells in the submucosa of the gut. If this makes no sense to you then read on and we’ll take a quick look at IgE mediated immunity.

IgE antibodies are proteins made by the body’s immune system that bind molecules from a potentially harmful foreign source. These foreign molecules, referred to as antigens, are normally proteins but can be a range of molecules including sugars, lipids or nucleic acids. Once made IgE antibodies are displayed on the surface of specialised immune cells called mast cells. When an antigen encounters a mast cell with the corresponding antibodies it binds and cross-links the antibodies, grouping them together. The cross-linking of antibodies causes a mast cell to release a bunch of molecules, including things like histamine, that lead to an immune response. This type of immune reaction, called a type 2 reaction to distinguish it from IgG-mediated type 1 reaction, is what we think of as an allergic reaction with symptoms ranging from sneezing, itching, and inflammation all the way to life threatening anaphylaxis.

Given the human suffering caused by allergies, you might ask why we have a type 2 immune response at all, but it does have a purpose. Primarily the type 2 immune response protects against helminth parasites, parasitic worms, that have been a problem all through our evolution and history1. The type 2 immune response is also important for wound healing and tissue repair after injury or infection2. As far as allergies are concerned problems arise when the type 2 response is misdirected against antigens from sources that do not really pose a threat, like pollen or food. There isn’t enough space to go into why this happens and why it seems to be increasing in modern society, the important thing here is that it does happen.

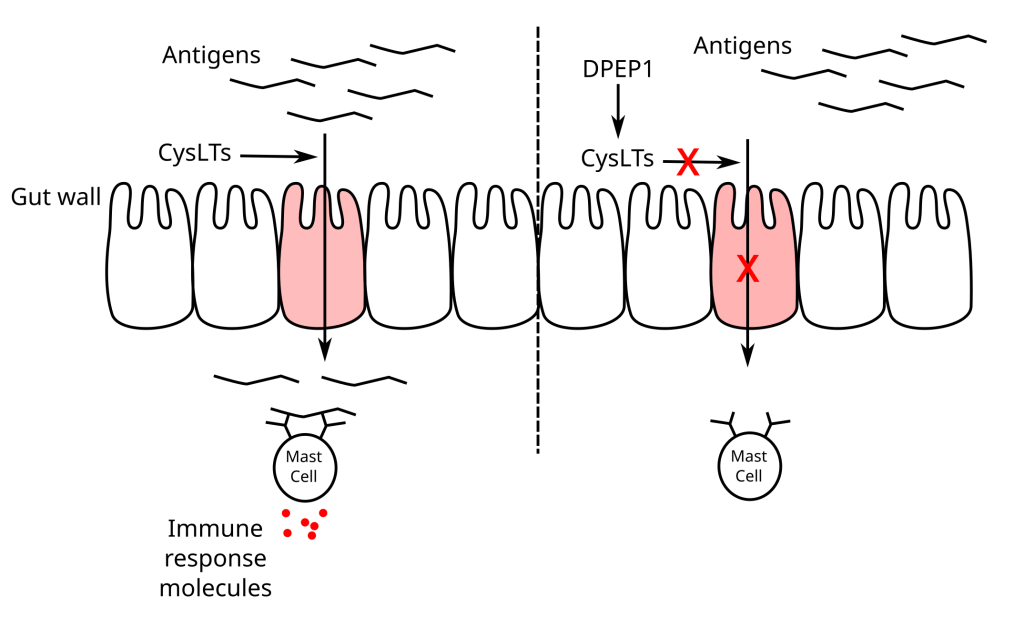

In the gut IgE-mediated immunity works in concert with a process called antigen sampling. To protect us from food borne infection a small number of antigens present in the gut are actively transported across the gut wall and exposed to mast cells, with their IgE payloads, in the submucosa. If any mast cells are displaying IgE antibodies to these antigens then an immune response will be initiated. If an antigen is from a food and you have a misdirected IgE antibody to that antigen then you will have an allergic reaction to that food. Antigen sampling is way for the body to ‘screen’ what is present in the gut and prepare the necessary defences if there is something harmful, this is really useful if you’ve eaten a parasite but not so much if you have a peanut allergy.

In the study we’re looking at the researchers compared the genes of the resistant and susceptible mouse strains and noted that susceptible strains had an impaired version of an enzyme called dipeptidase 1 (DPEP1). This enzyme breaks down a class of molecule called cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) which means susceptible mice would not be as efficient at breaking down CysLTs present in the gut. When the researchers measured CysLT levels in the gut sure enough susceptible mice had high levels of CysLTs in their gut and resistant strains had much less.

Working on the assumption that low CysLTs levels conferred resistance to a food allergy, the researchers were able to turn resistant mice into susceptible mice by blocking DPEP1 activity. More importantly they were also able to turn susceptible mice into resistant mice by impairing CysLT production using a drug called zileuton, a treatment for asthma. Combining these experiments with measurements of circulating antigen the researchers were able to establish that CysLTs have a previously unknown activity in promoting antigen sampling in the gut. The more CysLTs that are in the gut the more antigen sampling occurs and the more mast cells are exposed to antigens that cause a type 2 immune reaction. The reason that some mice, and people, are resistant to food allergies is because the antigens are never making contact with mast cells in the gut.

Like all good research this study has opened up a whole new areas of research. The exact mechanism behind CysLTs promotion of antigen sampling is not known, there is the possibility of a feedback loop where the CysLTs pathway is amplified during anaphylaxis, the human genetic variability for DPEP1 needs to be determined and correlated with allergy resistance and, as the authors point out, there are likely to be a whole range of genetic and environmental factors, like the microbiome for example, that influence antigen sampling. But importantly we now have a mouse model for looking at antigen sampling regulation and a FDA approved drug that may bring relief to sufferers of food allergies after accidental exposure to food antigens.

Footnotes

- The hygiene hypothesis is a theory that suggests that because we no longer are infected by parasites we are more likely to experience type 2-like immune dysregulation. In other words autoimmune disease and allergies have increased because the part of our immune system that deals with helminth parasites is no longer exercised in our youth. ↩︎

- More controversily, it has also been suggested that IgE mediated immunity may also be important for nuetralising toxins and venoms, like bee stings for example, and also may be involved in our defenses against cancer. ↩︎

Leave a comment