About Quick bites

Quick bites are shorter very specific posts that add some extra information that was too much for a regular post but which are worth knowing anyway. They can also highlight some important biological or chemical principle that can be referred to rather than explain the same thing over and over in different posts.

As Harold McGee points out in his book, On Food and Cooking, plants are essentially chemical factories. Plants are famously stationary and lacking any motive power must interact with the external world, for the most part, through a dazzling array of chemicals that they synthesise from basic chemical elements. The same plant will simultaneously produce chemicals to deter predators from snacking on important parts of the plant and produce fruit crammed with sugars specifically designed to appeal to animals. Thus conscripting them as a kind of reverse stork delivering seeds far from the orbit of their parents. Even more intimately plants manipulate bees and other pollinators into directly participating in their sexual reproduction, using sweet nectar to attract insects to it’s sexual organs.

In this short post I want to introduce some of the broad concepts behind plant-based foods and make sure we’ve got the necessary vocabulary to discuss the topics we’ll come across in later discussions.

Plants, are autotrophs, the manufacture all the complex molecules they require from basic chemical elements using sunlight as fuel. We’ve all at least heard of photosynthesis which is the biological process plants use to turn sunlight into chemical energy. Without plants animals could not exist. Animals need to consume either plants or plant-eating animals, or both, to get access to the molecules of life that plants manufacturer from scratch. Animals cannot harness sunlight directly and must use that chemical energy that, even if they are consuming another animal, ultimately comes from plants.

The plant pharmacopoeia includes a wide array of chemicals necessary for human life and health. Vitamins are one, for example vitamins C and A, and there is a bunch of molecules from plants, collectively called phytochemicals, that are important for human health. A few examples from this group include anthocyanins, carotenoids and flavonoids, which have roles in reducing cardiovascular disease, inflammation and oxidative damage.

Plants also produce a wide range of toxins, designed to deter predation, causing an arms race of sorts as animals evolved specific strategies for avoiding these deterrents. Humans, in particular, circumvented some of these toxins by developing ways of cooking that destroys toxins found in some plants. Humans also selectively bred plants producing varieties lower in toxins and thus more appetising for human consumption. Unfortunately for some species of plants, humans have also developed a taste for some of these toxins, think coffee, chillies, onions and mustard.

Plants are stationary, so they have developed roots that spread through the soil seeking water and the chemical elements they need, they have a system of internal transportation and support that moves essential molecules to and from the roots to wide canopies of leaf material with a high surface-area to volume ratio to capture the energy in sunlight and turn it to sugars through photosynthesis. In addition to roots, leaves and stems plants can also developed more specialised ‘organs’. Vegetables such as celery, turnips and beets are part stem and part root while rhizomes and tubers develop from underground stem tips, and include things like ginger, galangal, potatoes and yams. Rhizomes and tubers also form as a means of asexual reproduction, both structures are capable of developing into a full clone of the parent plant.

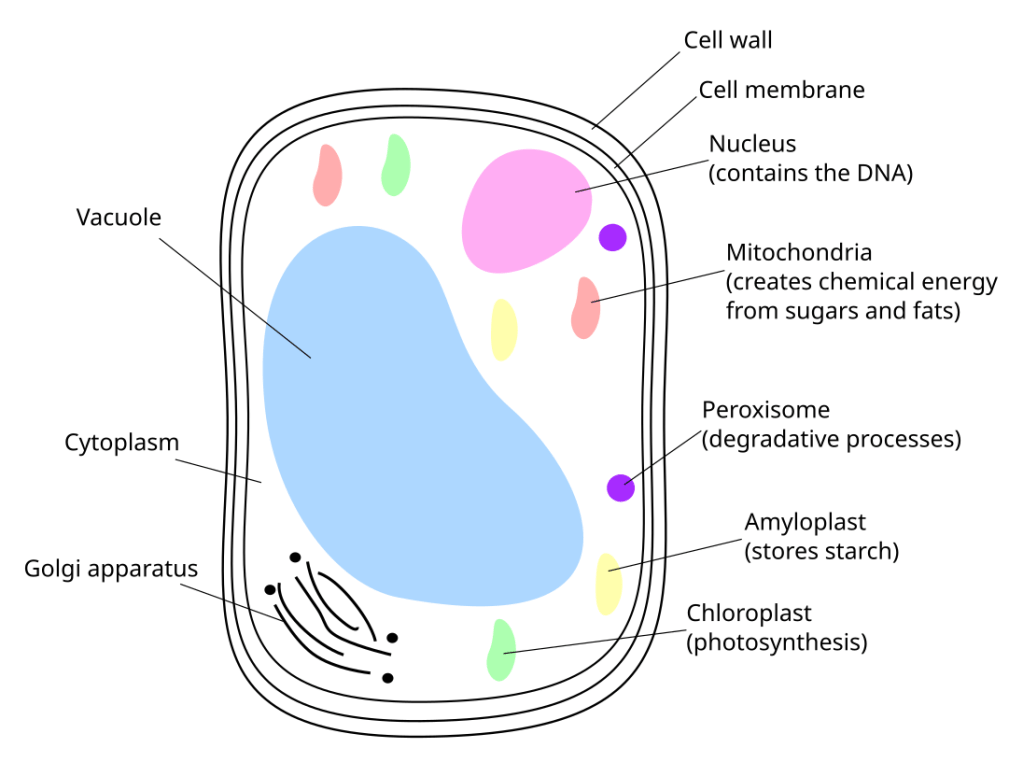

Plants, like animals, are made up of cells. Like animals plant cells contain sub-cellular structures like mitochondria, nucleus, golgi apparatus and peroxisomes suspended in an aqueous fluid called the cytoplasm. Plant cells also have some extra structures in the cell, the most important for us here are the chloropasts, where photosynthesis takes place, amyloplasts, starch storage containers, chromoplasts, where plants store and produce pigments, and almost all plant cells have a large ‘sac’ called a vacuole which contains a large number of molecules dissolved in water, including enzymes, defense molecules, acids and sugars. This vacuole can take up to 90% of the volume of the cell, pushing all the other structures of the cell up against the cell membrane.

Unlike animal cells, plant cells also have a cell wall. The cell wall is a relatively hard but flexible structure that surrounds the plant cell. It is primarily made up of long chains of carbohydrates called polysaccharides including cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin. Cellulose is a chain of glucose molecules that are bonded in way that provides long chains of tough fibres and the cellulose-hemicellulose network is embedded in a matrix of pectin and other molecules. Cellulose is invulnerable to human digestive enzymes and needs quite extreme temperature or chemical conditions to breakdown. Because of this almost all the fruit and vegetables that we eat have thin cell walls. Which makes sense if you consider trying to chew something containing a lot of cellulose. Wood, for example, is one third cellulose and we don’t have too many dishes using wood. Despite being indigestible cellulose is still important to the human diet as the major component of dietary fibre.

The cell wall and vacuole are what gives fresh vegetables and fruit their firmness. When filled with water the vacuole pushes up against the cell wall and this pressure provides a firm fruit or vegetable. When there is no water, for example if it’s sat in your crisper for a week losing moisture, then this pressure dissipates as the vacuole shrinks and the whole thing becomes limp and flaccid. It also provides the crispness of a fresh fruit and vegetable as when under pressure the cell walls are already under duress so break easily when bitten into. When flaccid and under no pressure we have to provide energy by chewing to get through the cellulose rich cell wall.

This has been a lightening fast trip through botany as it relates to cooking. But if you take anything anyway from it let it be that plants have cell walls, large water-filled vacuoles and special containers for starch. Animal cells do not have these structures and it is this that mostly distinguishes the science of fruit and vegetable cookery from the cooking of animal products.

Leave a comment