A wag once noted that the two things that no one will ever admit to being bad at are sex and cooking a steak. But, after years of denial and some recent self examination I need to be honest and confess that my steak cooking is not what it could be. Time after time I either overcook the steak while trying to get a good sear or I get the middle done nicely but have an insipid sear on the outside.

I know others have the same problem, though they’ll never admit it. But I watch them at their BBQs, I furtively spy on their steak cookery and I subject their cooked steaks to a silent, internal but brutal forensic evaluation, and I know they are no good either. Endless summer BBQs with steaks either seared to rubber or pale and lifeless like some type of soybean meat substitute. I suppose getting a correctly done steak is more important than an aesthetically pleasing sear but there is a lot of flavour in that sear and having both would be nice. I’m a scientist, of sorts, can science help up my steak game? It couldn’t do any harm I suppose. To learn a little something about how to cook steak. And I guess science can help me more with this than with my other hard to admit problem …

When it comes to the science of steak it all starts with anatomy. The biological structure of the meat we are intending to cook. The choice of cut is the first and most important decision you need to make. Slow cooking, smoking and braising can come later, what we are talking about is cooking a piece of meat relatively quickly over some type of direct heat. Your hob or your grill being the two most likely candidates. Only some cuts of meat will react favourably to this treatment. No amount of cooking wizardry is going to let you cook a brisket the same way you cook a piece of sirloin. The reason for this is anatomy, and proteins, but if you’ve read any other posts on this blog you might have guessed that proteins are always involved somewhere. So the first step towards better steak cookery is understanding what cuts of meat make for a good steak.

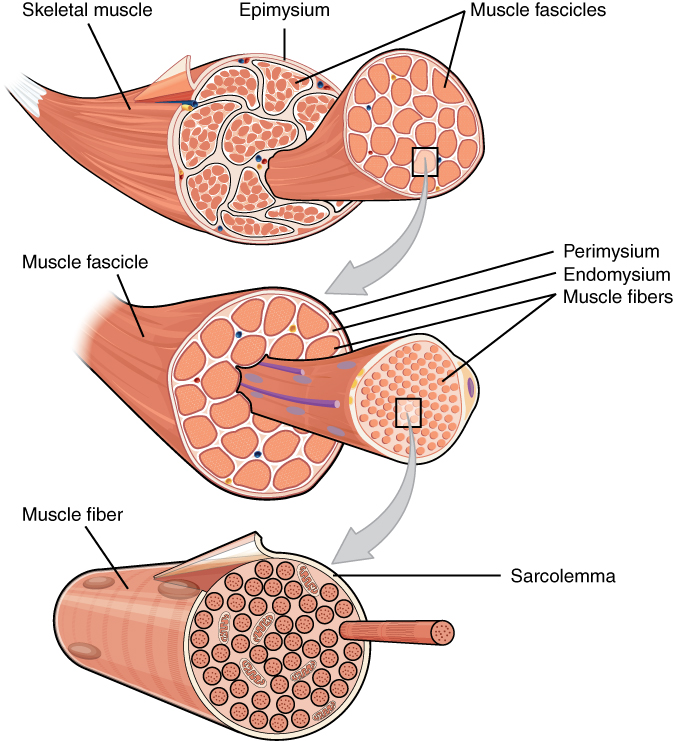

In these days of plenty what we usually mean when we refer to meat is muscle tissue. Things like liver or kidney, usually referred to as offal, have their own structure and cooking techniques. Muscles are the things that provide the locomotive power of organisms. To provide this power muscles have a unique structure. The basic unit of muscle anatomy is the muscle fibre, a long cell that contains, amongst others, a protein called myosin. You can think of myosin as a kind of motor and it’s interactions with another protein called actin is what makes it possible for muscles to contract. Muscle fibres are grouped into structures called muscle fascicles and the fascicles are themselves grouped into bundles that make up the muscle.

All these bundles are surrounded, organised and held together by connective tissue. The connective tissue is made up of cells but also of proteins that are secreted by these cells, the most important one for us being collagen. When you are handling raw meat you can often see the connective tissue as a thin silvery membrane that separates different parts of the meat. The cells in connective tissue can also store fat and when they do this they are called fat tissue. In muscle, parts of the connective tissue surrounding bundles of fibres and individual muscles can become fat tissue and this is what gives us marbling, the thin trails of fat you often see running through a steak. You may have heard the saying that fat is flavour and in steak this is absolutely the case. Protein and connective tissue probably don’t vary in flavour from animal to animal. But fat, which can have anything dissolved in it, is what makes beef taste like beef, lamb like taste lamb and something like chicken breast, with no marbling, taste like, well, nothing.

So what does all this mean when we’re choosing our steaks? Well, a general principle with meat is that the more that a muscle is used by the animal the tougher it will be. When muscles are used a lot the total number of muscle fibres stays the same but they become bigger as more of the contractile proteins, myosin and actin, are produced within the muscle fibres. More protein means that the meat will be ‘tougher’ especially after it has been cooked (see the frying an egg post for an explanation of what heat does to proteins). Well-used muscles will also have more supporting connective tissue and thus more collagen and collagen is what makes connective tissue tough and hard to chew.

Given this, the toughness of a piece of meat will be primarily influenced by the age of the animal, older animals will have done more with their muscles, and where on the animal the meat comes from. On four-legged animals the muscles of the neck, chest and legs work hard, whereas the back of the animal is more relaxed. Accordingly, cuts like brisket which come from the front of the animal will be tougher than tenderloin which doesn’t do a whole lot of work. Compared to the tenderloin, brisket will have relatively larger muscle fibres and relatively more connective tissue (tenderloin has almost no internal connective tissue) which makes it a much tougher cut of meat. For a good steak what we want are the tender comparatively under-used muscles, cuts like sirloin, tenderloin and rump for example.

Now we’ve chosen our meat we want to cook it. If you haven’t read it already it might be worth having a look at my post on frying an egg. Because the aim of cooking a steak is exactly the same as when frying an egg. What we want to do is denature our steak proteins using heat while trying to avoid squeezing out too much water from the steak as the proteins coagulate. Myosin will ‘unravel’ and start coagulating at around 50C/122F so if we have a rare steak (~48C/120F) we will basically be eating uncoagulated proteins but all the moisture will still be in the steak. We can get away with this with a tenderloin because it is already tender, if you try it with brisket you’d still be chewing. A medium steak, say at 60C/140F, will have more coagulation and more moisture ‘squeezed’ out and a well-done steak (71C/160F) will have most of the protein coagulated and interacting tightly with each other and a lot of the moisture gone, so dry and tough. Just like frying an egg.

There is one more important temperature for cooking muscle tissue. At around 70C/160F collagen starts breaking down to gelatin. We all know gelatin, it’s what you use to make jelly, and it can make a piece of meat ‘juicy’ again. The reason that a well-done steak is dry and tough is because a steak doesn’t have much connective tissue, so if you cook it above 70C you’ll get coagulated muscle fibre proteins but no gelatin because there isn’t much collagen. Brisket on the other hand has a bunch of collagen so it needs to be cooked for a long time above 70C so that all that collagen will breakdown to gelatin. Once this is achieved almost all the moisture will be squeezed out of the meat by coagulating muscle proteins but the large amount of gelatin that comes from the collagen degradation will make the meat feel juicy when eaten. The juiciness of a juicy steak and a juicy brisket are two different types of juiciness.

The other part of the steak cookery puzzle is the sear on the steak. Often incorrectly called caramelisation, the sear on a steak is actually an example of Maillard reactions. In technical terms the Maillard reactions are a form of browning that occurs when proteins react with sugars. Sugars will be covered in future posts, but for now it is enough to know that chemical reactions between proteins and sugars on the surface of the steak creates many new, and poorly understood, compounds that give the steak a browned appearance and which are, from our perspective, delicious.

The Maillard reaction doesn’t just occur on steak it is responsible for a lot of the flavour in a whole bunch of foods including the crust on bread, chocolate and roasted nuts, to name a few, and is an important part of the beer and whisky making processes. So for a flavourful steak we really want to cause some Maillard reactions on the surface of our steak. The problem with this is that the Maillard reactions happen well over 100C/212F, most rapidly between 145C/293F and 165C/329F, which is well above the temperature that we want our steak to be at, say 54C/130F for a medium rare steak.

So lets put all this together. We have a tender steak that we want to cook to juicy perfection at medium rare, for example, with lots of tasty Maillard reactions on the outside. A tender steak has little connective tissue and thus little collagen. On the grill or hob we wont have the time to slowly render our collagen to get gelatin, but that’s fine, there isn’t much collagen in our steak anyway. What we really want to do is get the center of our steak to around 54C so our proteins are coagulating to some extent but we haven’t lost too much juiciness from the steak. At the same time we want the surface, and just the surface, to get to a temperature high enough to trigger some Maillard reactions that will give us a nice sear and some complex flavours and this temperature is about 100\degC higher than what we want the inside of our steak to get to.

Ultimately this is what makes grilling a tender cut of meat so challenging, coals glow at around 1100C/2012F and gas burns at 1650C/3002F. Because the temperature gradient is so steep it is very easy to overcook a steak as the internal heat increases very quickly, the high temperature also means that even if you get the middle of the steak right the outer parts of the steak can be overdone. If we cook at much lower temperature the temperature gradient will be a lot shallower giving us more time to react and keeping the outer parts of the steak less overdone but we will struggle to get some good searing on the steak. What are we to do?

A common strategy is to do both. We cook the steak to our required temperature using slow heat and then sear quickly over high heat, or, sear quickly over high heat and then finish cooking using slow heat. For example, the most fool-proof way of cooking a steak is to use sous vide, a fancy name for a water bath. You set a water bath for your desired temperature, say 54C, and you drop your vac-packed steak into the water for an hour or so. After it’s cooked you sear the steak at a very high temperature on the grill, the hob or even using a blowtorch. You cannot overcook your steak using a sous vide because it is impossible for the steak to get to a higher temperature than the temperature of the water around it. But, standing around a water bath with a beer lacks the drama of searing steaks over hot coals, might be good for a dinner party but if you want serve steaks of different doneness you’ll need multiple water baths.

The restaurant strategy is to quickly sear the steak over high temperature and then put it in the oven to finish and this works well when cooking at home as well, taking out the steaks as they reach the desired temperatures. On the grill you can mimic this technique by setting up a two zone grilling zone, you arrange the coals or turn down gas elements, so that there is a hot part of the grill and a relatively cool part of the grill. Sear the steak on the hot part of the grill and then finish it off in the cool zone until your happy with the doneness. Finally, you can cook a steak perfectly well using a single pan on the hob, make it a heavy heat-retaining pan like a cast-iron pan, and start with a hot pan and turn down the heat once you are happy with the sear. Butter can help with the browning so towards the end add butter to the pan and start basting, this method probably takes more practice to get right and probably works for small amount of steak, it would be hard for a larger event.

Once we have cooked the perfect steak there is one more absolutely essential step. The steak must be rested. It’s hard when guests are demanding to be fed or you haven’t eaten all day but do not serve that steak till it has rested (or any whole tissue meat for that matter, you don’t need to rest sausages or hamburgers). The reason for this is that an unrested steak will leak a whole bunch of liquid, the sweet juiciness we worked so hard to preserve, unless you let the internal temperature of the steak come down a bit. Remember that the bundles of protein in the steak coagulate and squeeze out water, coagulation is irreversible but as the temp comes down the proteins will relax a bit enabling them to retain a bit more water and prevent the leakage of fluid when you finally cut into the steak.

Cooling will also thicken up the fluid left in the steak, though less important than for low and slow cooked cuts with plenty of collagen, whatever gelatin that has formed will thicken up the juices as the steak cools. For a steak you can probably get away with 5-10 minutes resting but longer wont do any harm at all, use the time to get side dishes on the table. Not resting your steak is the number one amateur mistake when cooking steak. So you’ve been warned – rest your meat before serving.

So that’s it, we’re maybe a little better prepared to cook some good steaks for our friends and family. This is another long post so I’ve left out a lot, things like salting your steak, making sure it’s dry, the different types of muscle tissue that give as light and dark meat and a whole bunch of other things that we probably need to know. So, I’ll be writing more about steak cookery. But I’m hoping this is a good enough start to let us stand a little taller at BBQ time and be able to honestly say that we don’t suck at cooking steak.

Extra stuff

Searing does not ‘lock in moisture’

Searing the steak does not seal in moisture, if it did we wouldn’t have to worry about drying out our steak, we could just sear it and cook it as long as we wanted. This piece of voodoo science is remarkably persistent, I’ve heard Michelin starred chefs telling people to ‘seal in the moisture’, on many a cooking show and I fly into a nerd rage every time.

Leave a comment